Health

What Do Weather Forecasts and Health Studies Have in Common?

New research shows the promise and challenge of predicting health outcomes

Posted August 29, 2019

A meteorologist and an epidemiologist walk into a bar…

When a meteorologist gets the forecast wrong, the consequences are a minor inconvenience: you get wet in an unpredicted rainstorm or you miss out fishing on what turns out to be a sunny day. But when health researchers get a forecast wrong, the consequences can be major. And because of this, my advice is for you to never confuse expertise for clairvoyance.

It is not difficult for me, or for any health researcher with a minimal amount of training, to describe what has happened (i.e., to describe the past). This is what most health research is: conducting an experiment, or following a cohort over time, and then describing what happened. Sometimes this description occurs within the context of a particular prediction of what was likely to happen, called a hypothesis. So, I might hypothesize that eating a diet low in fat would reduce depressive symptoms. I could design an experiment, or observe what happens in a large cohort of people followed over time, to test that hypothesis against the “null hypothesis” (that is, that there is no relationship between diet and depressive symptoms). This would be an exercise in describing the past, even though that description occurred in the context of a hypothesis that was about the future (i.e., what would happen if…).

That is a very different exercise than forecasting, which involves saying “In Study A, I observed X. And from the results of Study A, I predict Y will happen to this other group of people (Study B).” Of course, this forecasting exercise is exactly what we all do when we take the findings from a research study (that was conducted on other people and occurred in the past) and try to apply its findings to our future health. The challenges of forecasting are apparent to anyone who has tried to create a winning March Madness bracket - the past has imperfect information about new situations.

The other issue is that often gets lost when we try to apply the results of studies to our lives is that we don’t appreciate that we are moving from the domain of the relative to the domain of the absolute. That is, the estimate generated in health research almost always only describe how much more (or less) likely an event was to happen in one group versus another (e.g., the group that ate the low-fat diet vs. the group that did not). They generally don’t describe, in absolute terms, the likelihood that an event actually occurred, which would be quantified by values such as attributable risk or number needed to treat. This matters because health events are like the weather in many ways: humidity is a continuum, and the higher the humidity is, the more likely it is to rain on a given day. But weather (like health events) events are binary: it rains or it doesn’t. You have a heart attack or you don’t. Higher humidity is not the same as rain, just like having a relatively high probability of a health event is not the same as having the event itself.

There's another parallel between meteorology and epidemiology that warrants attention: Just like the weather is easier to predict in places like Phoenix than it is in places like Detroit, some health events are easier to predict than others. I’d be willing to bet you $100,000 that it will be sunny in Phoenix a week from now, but I wouldn’t take that same bet for Detroit. Why not? Because Detroit’s weather is harder to predict because there are more variables in play there (e.g., proximity to the Great Lakes which affects wind, air temperature, and humidity). What types of health events are relatively easier (but still difficult) to predict? Whether you will develop cardiovascular disease in the next 5 years. What types are harder to predict? Whether you will die from suicide in the next 5 years.

One more point: We don’t need to know the causes of disease in order to predict who is most likely to get them. The weather on August 30, 2019 is one of the best predictors of the weather on August 30, 2021, but that doesn’t mean that the weather in 2019 causes the weather in 2021 - it is just highly correlated with it. In that same manner, we can predict your risk of death in the next 10 years from a handful of factors that are sufficiently correlated with the direct causes of your health – including factors that don’t have any direct relationship to your body, like your zip code, how much education you completed, and the value of your home – to satisfy any Vegas house odds, even though we can’t point to any one of them as the causal factor.

This idea of predicting the ultimate health outcome - death - was in the news recently. Headlines included “Scientists develop a blood test that predicts risk of death,” and “Blood test will tell you if you’ll die within 10 years.” A few study details that matter here: the authors used data from 12 different cohorts with a mean age of 63.1 years across the samples. All the cohorts were from Europe and the predictive accuracy of the test was only evaluated in samples of people of white European descent. So unless you meet that description, the findings from this study don't apply to you.

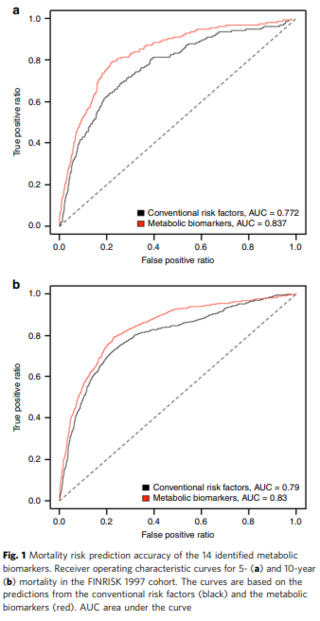

The other issue - that didn’t make it into the headlines - is that we have been able to predict risk of death with better than a coin-flip accuracy for a long, long time. The authors compared their blood test to a composite of “conventional” risk factors - things like smoking, history of major health conditions (cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease) - and while it did better than the conventional risk factors, it didn’t blow it out of the water (see this figure from the paper, which is publicly available). Overall, the blood test predicted 10 year probability of dying with 83% accuracy; the conventional risk factors predicted it with 79% accuracy. Those both feel like “8 in 10” to me, but of course, I don’t write news headlines.

This begs the question of course, which I think is very much worth asking: “Why was the blood test even marginally better than conventional risk factors?” Let's look at what went into them. The conventional risk factor score included 12 variables: sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, creatinine, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and prevalent diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Almost all of these factors increase risk of death. In contrast, the blood test included 14 variables, the majority of which (8 of the 14) were protective against death. In my opinion, the insight from this paper isn’t that they created a blood test to predict death - it is that they created a prediction model that had a balance of “things that kill you” and “things that make you stronger.”

Finally, let me suggest an alternative framework for considering how the findings from health research apply to your life: What do you need to know, and why do you want to know it? That is, manage your expectations of the role of health research in your life. I presume that the reason you want to know the findings of health research is so you can change your behavior in discrete but meaningful ways, in the same way you want to know the weather forecast to know whether you should put on a coat, bring an umbrella, or pack sunscreen. That’s it.

The lesson for clinicians - and patients - to take from research that when it comes to predicting the future, you need to look at the whole picture. In that way, health isn’t any different than prediction of any other type, whether that is your March Madness bracket or whether it will rain tomorrow.

References

Deelen et al. (2019) A metabolic profile of all-cause mortality risk identified in an observational study of 44,168 individuals. Nature Communications. Volume 10, Article number: 3346. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-11311-9#Sec14