Animal Behavior

Underdogs: Treating Needy Pets in Disadvantaged Communities

An important new book looks at dogs' and cats' lives in low-income settings.

Posted January 21, 2021

"The problem of getting basic veterinary services to dogs and cats in low-income communities has suddenly become spotlighted as a major issue facing animal shelters, animal rescue groups, animal control departments, and veterinarians in the United States and abroad."

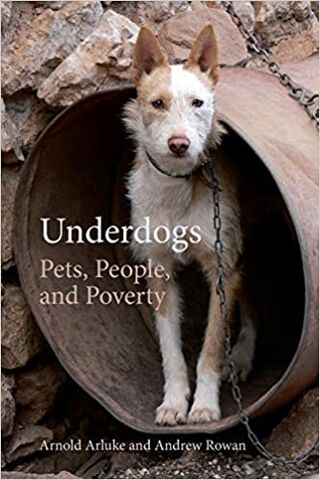

Dogs and cats are "in." Numerous people around the world share their homes, and hopefully their hearts, with canine and feline companions. Nonetheless, a good deal of care that is offered to these amazing nonhumans is confined to places where people can afford to pay for it. Surprisingly, pet owners living in or near poverty do not always use free or low-cost veterinary care when it is offered to them. Understanding why this happens and what can be done about it are critical questions facing animal advocates who want to promote the welfare of all pets. I'm thrilled to offer this interview with Drs. Arnold Arluke and Andrew Rowan about their new and extremely important book called Underdogs: Pets, People, and Poverty, about the lives of dogs and cats living in disadvantaged communities.1,2,3

Why did you write your Underdogs?

Estimates are that about 19 million pets living in underserved communities receive little if any veterinary care, such as essential vaccinations, basic checkups, sterilization, or treatments for basic medical problems. Some veterinarians see this lack of access as the profession’s foremost crisis today, causing anguish and distress for many pet owners.

This omission is starting to slowly change in recent years with the growth of programs, often attached to animal shelters, that provide low or no-cost basic veterinary services to disadvantaged pet owners, including sterilization, vaccinations, wellness exams, basic treatments, pet food, and even fences to unchain dogs. However, when cost or access barriers are removed, some pet owners (an estimated 20% of the underserved population) fail to take advantage of these services or are slow to do so.

We compared shelter-based programs in Costa Rica and Charlotte, North Carolina to see if barriers other than cost and accsess, such as culture, race, and class, might impede equal access to veterinary services by all segments of the pet-owning population. And to see if these barriers are sometimes overcome, we studied how providers of free or low-cost services in these two locations managed non-financial obstacles to disseminating basic veterinary care.

How does Underdogs relate to your backgrounds and general interests?

Co-authoring Underdogs blended our expertise in social science research and animal public policy. As a sociologist and ethnographer, Arnold spent over 35 years studying different kinds of human-animal relationships, including those experienced by animal cops, shelter workers, animal control officers, veterinarians, laboratory animal scientists, animal abusers, hoarders, rodeo participants, animal photographers and everyday pet owners. Andrew has spent 40 years studying companion animal demographics and the human-companion animal relationship in North America and around the world. For 20 years, he oversaw projects addressing the humane management of street dogs around the world, especially in Asia and Latin America. More recently, he has also focused on human populations with limited access to veterinary care for their companion animals.

Who is your intended audience?

We wrote Underdogs to help policymakers, animal advocates, and service providers disseminate affordable veterinary care. Programs that provide these services will better understand the factors that limit their success or increase their effectiveness, tailor and customize their operations to reach a wider audience of underserved pet owners, and advocate for changing legal policies that impact the delivery of their services to those in need. We also wrote Underdogs for scholars and the laity alike who want to understand how culture, class, and race shape pet keeping and caring.

What are some of the topics and messages in your book?

Beyond cost and access, we found other obstacles to disseminating affordable basic veterinary care, although these barriers differed in the two locations. In the most underserved areas of Costa Rica, dogs and cats were not “owned” in the modern western sense and were thought to be independent enough to fare well on the streets, so taking them for basic veterinary care was neither someone’s responsibility nor something viewed as necessary. Compounding this reluctance, groups trying to provide veterinary care to the underserved sometimes competed for the same clients in ways that complicated or prevented the delivery of low-cost services. For example, private practice veterinarians, fearing they would lose clients to shelter outreach programs that offered low-cost sterilization, sometimes tried to restrict the amount of free or discounted services given to the underserved.

In the most underserved part of Charlotte, there were different barriers to disseminating affordable veterinary care. Some people distrusted the shelter because its sterilization program reminded them of the state’s forced sterilization of young black women as recently as 1974. Others felt ashamed or even stigmatized to take free services. And yet others were afraid that law enforcement or immigration authorities would track them down through personal information they gave to the shelter.

In both settings, shelter outreach programs tried to overcome these barriers so more animals would get basic veterinary care. In one respect, the shelters took a similar strategy: workers reduced their expectations of what underserved communities can reasonably do for dogs and cats, given the realities of living in or near poverty and the constraints of local culture. The notion of “responsible guardianship,” often touted as the gold standard for pet owner behavior, was impossible to achieve and also risked further alienating communities that have long distrusted shelters, so rather than prohibiting or discouraging pet ownership in underserved communities, shelter workers aimed for reasonable guardianship.

They also tried to change how people interacted with their animals to increase their attachment and consequently their willingness to use free or discounted veterinary services. In Costa Rica’s underserved communities, outreach workers tried to shift the view of dogs and cats to be more like the modern, western conception of pets. For example, people who had never held, cradled, or leashed a dog or cat were encouraged to do so when they brought animals for sterilization. The program in West Charlotte also changed how people interacted with their pets. For example, building backyard fences enabled unruly dogs to become more approachable, in turn making it easier for owners to touch or play with their pets. The shelter also worked at increasing the local community’s trust in its intentions and programs. For example, workers cultured special relationships with “community ambassadors” knowing that people who had used the shelter’s affordable care and spoke highly of it would encourage neighbors with pets to also use these services.

In short, programs providing free or low-cost services must consider the cultural, racial, and class context of the communities they serve to make palatable the offer of affordable care. In the end, they will be effective not only because cost and access barriers are removed or reduced, but because they also address larger issues facing pet owners living in or near poverty.

How does your book differ from prior research on veterinary care in underserved communities?

Underdogs is the first book to detail the plight of millions of underserved pets, the reluctance of their owners to use free or low-cost basic veterinary services, and the efforts of animal advocates to remedy this problem in Costa Rica and the United States. Our work is also the first to explore the ways that social class, race, and culture shape human-animal interactions in disadvantaged communities.

References

Notes

1) Arnold Arluke is professor emeritus of sociology and anthropology at Northeastern University and senior fellow at the Tufts Center for Animals and Public Policy. He is a cofounding editor of Society and Animals and has published over one hundred articles and twelve books, including Regarding Animals, Brute Force: Animal Police and the Challenge of Cruelty, and The Sacrifice: How Scientific Experiments Transform Animals and People. Andrew Rowan founded the Tufts Center for Animals and Public Policy and started the first graduate degree in the world on animals and public policy in 1995. He is the founding editor of Anthrozoös and author and editor of numerous books on human-animal issues including the four volume State of the Animals series. He is president of WellBeing International, a new NGO seeking solutions for people, animals, and the environment.

2) The book's description reads: Underdogs looks into the rapidly growing initiative to provide veterinary care to underserved communities in North Carolina and Costa Rica and how those living in or near poverty respond to these forms of care. For many years, the primary focus of the humane community in the United States was to control animal overpopulation and alleviate the stray dog problem by euthanizing or sterilizing dogs and cats. These efforts succeeded by the turn of the century, and it appeared as though most pets were being sterilized and given at least basic veterinary care, including vaccinations and treatments for medical problems such as worms or mange. However, in recent years animal activists and veterinarians have acknowledged that these efforts only reached pet owners in advantaged communities, leaving over twenty million pets unsterilized, unvaccinated, and untreated in underserved communities. The problem of getting basic veterinary services to dogs and cats in low-income communities has suddenly become spotlighted as a major issue facing animal shelters, animal rescue groups, animal control departments, and veterinarians in the United States and abroad. In the past five to ten years, animal protection organizations have launched a new focus trying to deliver basic and even more advanced veterinary care to the many underserved pets in the Unites States. These efforts pose a challenge to these groups as does pet keeping to people living in poverty across most of the world who have pets or care for street dogs.

3) A large number of dogs, often called "streeties", also need better care. It's good news that the government of India has declared feeding streeties to be an essential service and political leaders are appealing the people to step up to their responsibility of taking care of these animals. Many people are only familiar with "homed" dogs and it surprises them when they learn that hundreds of millions of dogs are free-ranging and live with minimal or no support from humans.

Bekoff, Marc. How Will Dogs Reshape Nature Without Humans to Control Them?

_____. As Dogs Go Wild in a World Without Us, How Might They Cope?

_____. Personality Traits of Companion and Free-Ranging Bali Dogs.

_____. Changing Behavior of India's Street Dogs During Lockdown. (India's government has declared feeding "streeties" to be an essential service.)

_____. Canine Confidential: Why Dogs Do What They Do. University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Pierce, Jessica and Marc Bekoff. A Dog's World: Imagining the Lives of Dogs in a World Without Humans. Princeton University Press, Fall 2021