Relationships

Does Your Parents' Failure Mean They Didn't Love You?

Deliberate grieving may allow us to see they did the best they could.

Posted February 28, 2021

Yesterday was my mother’s yahrzeit, the anniversary of her death. Three years later, I find myself thinking about her often, and differently than I did when she was alive. A middle-aged orphan with two wonderful siblings, I learn more about her as I get older, and as her powerful personality no longer shades my insight into our relationship.

In a long period of depression in my 30s, I had therapy with a man who occasionally presented pithy observations, like this one in response to my struggle to reconcile my mother’s loving intentions and her failure to give me the support I needed: “Parents typically do the best they can.”

As I’ve noted elsewhere in this blog, my mother had an intense relationship with her father who, like her, was fiercely intelligent and could be devastating with his teasing and wit. A law professor fascinated by Lizzie Borden (the woman acquitted of murdering her parents with an ax), Grandpa arranged a series of photographs of 5-year-old Mom dressed as Lizzie. A “joke”? A peculiar objectification, painful and distancing. Nothing to do with reality. But whenever Mom looked at the series of small black-and-white photos of herself wielding an ax as tall as she was, she would turn away, hiding her stricken face from me. She couldn’t tear the pictures up, but she couldn’t bear them either. Her father’s motivation was inexplicable.

Caught in the bind of her own role as a (murdering) daughter, Mom didn’t see that her catchy ditty about my “greasy little feet on the kitchen floor” might affect me as she was affected by her father’s “pre-Freudian” joke. My feet were not greasy—the song was nonsense. But it was also a failure of empathy, and it hurt me. When I was a teenager, all she had to do was whistle the tune to “greasy little feet on the kitchen floor” and I would be overcome with silent shame and rage.

I have no doubt whatsoever that my mother’s teasing song—its origins forgotten—was composed in love and enjoyment of her little girl, and was sung (or later whistled) in disbelief that it could possibly hurt me. Presumably, her father’s concept of the Lizzie Borden photo-shoot was similarly distorted by confidence in the love he truly felt for his little girl. Sometimes parents simply cannot get beyond a childhood experience of dysfunctional family dynamics, and they subconsciously re-enact it with their own child, rewriting the meaning of the act.

In the years since her death, I have attached a moment with Mom to my memory of the “greasy little feet” song. The moment resonates with forgiveness and has eased my grief.

Twenty years after Mom last whistled that song, I went to stay with her for a while as I healed a broken heart. One morning we sat at the dining room table, coffee mugs in front of us. “I worry that there are things I didn’t do right for you,” she said.

The words made tears spring to my eyes.

She went on: “I always wondered if we should have sent you to that diabetes camp when you were a girl.”

I shook my head. “I would have died of shyness if you had.”

We smiled. I knew that in our respective lives we each had covered a chasm of insecurity with a gloss of confidence.

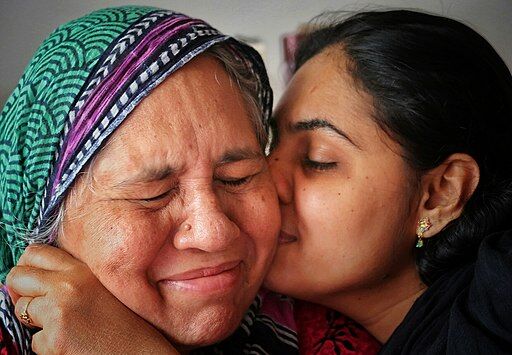

She started crying, so of course I did too. “I hope you know how much I have always loved you. If there are things that I didn’t do right, I hope that you will let me know, so that we can make them right.”

I put my hand on hers, which was the exact same shape as mine. Her skin was fragile, had age spots and wrinkles. I said, truthfully, “There is nothing that needs to be made right.”

Her hazel eyes were watery gray as she looked directly into mine. “I tried my best,” she said. I know that she did. And that’s all that any of us can do for the ones we love.