Decision-Making

The Twitter Files, the Laptop, and Human Decision-Making

Twitter Files 1 highlights a lot of human decision-making issues.

Posted January 9, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Ideological thinking can create blind spots.

- We often find what we look for in ambiguous situations.

- We tend to be more accepting of less-consequential errors and can reason our way into a lot of things.

By now, many folks have heard of the Twitter Files, which involved screenshots of various internal Twitter documents (e.g., memos, messages, emails, chat logs) released by different journalists (with releases still ongoing). Having reviewed many of the exposés that have been released, what is most striking to me is the way in which many of them provide examples of some of the decision-making topics I write about on this platform. Since an in-depth analysis on all the Twitter Files is impossible in one post,1 I consider only the first thread released by Matt Taibbi, the one covering the Hunter Biden laptop story. Here are a few key takeaways from Twitter Files 1 as they concern human decision-making.

Ideological Thinking Can Create Blind Spots

Twitter employees, like those of many other technology companies, tend to have a strong skew toward Democratic Party candidates. According to Open Secrets, for the cycle 2022, under the category of All Federal Candidates, 99.7 percent of political contributions made by Twitter employees or their family members were made to Democrats. While not strong evidence of pure ideological homogeneity, it does point to the conclusion that Twitter may have been at least somewhat of an ideological echo chamber where politics was concerned.

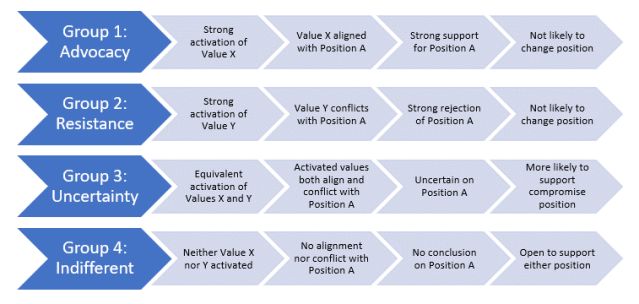

This appears to be intimated by Taibbi (Figure 1) in his discussion of the Twitter files. As I wrote when discussing ideological biases, too little ideological diversity can result in echo chambers, often producing decisions with undesired consequences. The reason for this, as presented in Figure 2, is that too many decision-makers often end up in Group 1, the advocacy group, which leads to a lot less pushback on decisions that align with shared ideological biases.

The takeaway: We need to be careful about creating ideological echo chambers, as they can lead to decisions that produce unintended consequences.

We Often Find What We Look for in Ambiguous Situations

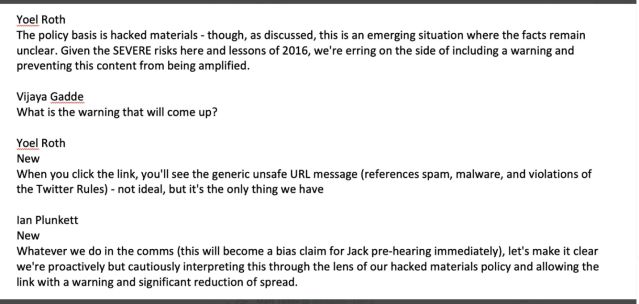

But there’s an added layer of complexity to this issue. In the lead-up to the election, senior Twitter employees were primed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to be on the lookout for potential hacked material and attempted foreign influence on the election (Figure 3).

The actions by members of the FBI, regardless of their intentions, likely created a secondary bias2 that would affect the interpretation of new information that might alter the election results. When the New York Post released its story, it was unclear at first how credible the story was or how the information was acquired. Subsequently, the bias kicked in: The initial judgment3 was that the story was dubious. Because there was too little ideological diversity among key decision-makers, there was also scant evidence of pushback against the biased interpretation.

The takeaways: (1) If you’re biased toward a given conclusion, you’re likely to reach that conclusion when there’s no obvious reason to reject it.4 (2) Seeking feedback from those who already agree with you will simply reinforce your acceptance of the biased conclusion.

We Tend to Be More Accepting of Less-Consequential Errors

The exchange presented in Figure 3 also demonstrates how the bias toward concluding that the laptop story was not credible also led to a particular response. According to at least one Twitter executive, the consequences of taking no action against a questionable article that may turn out to be in violation of Twitter’s posting rules were perceived to be much greater than the consequences of taking action to censor an article that may turn out to be legitimately sourced.

Even if there were suspicions that the laptop story may not have been a violation, error management theory5 proposes that in a decision situation that contains ambiguous information (i.e., the conclusion is unclear based on the evidence), we tend to be more accepting of errors that have the least severe consequences. In this case, it was perceived that a failure to censor a dubiously sourced article was much more severe than the censoring of an article that was legitimately sourced.6 There is the potential that existing ideological biases influenced this conclusion, but it’s unclear (at least based on what we know) why one outcome was perceived as more severe than the other. All we do know for sure is that the situation caused the activation of specific values that then guided decision-making in that situation.7

The takeaways: (1) When we’re unsure what to do, we’ll tend to default to the action we perceive would be least consequential if it turns out we’re wrong. (2) The consequences of different errors will be assessed based on specific values activated in that situation.

We Can Reason Our Way Into a Lot of Things

The decision had been made to censor the story, but executives had no evidence on which to base that decision. Given the likely repercussions of censoring the story, a reason needed to be provided to justify the resulting action. That reasoning turned out to be the claim that the story violated Twitter’s rules against posting hacked materials. There was, of course, no evidence to suggest the story was based on hacked materials, but there was also no evidence to suggest it wasn’t. Since Twitter executives needed reasoning behind their actions, the hacked materials rule served that purpose.

As I discussed when writing on motivated reasoning,8 we can often reason our way into taking a specific action, but we need to muster up the logic needed to support that action. We don’t always do so ahead of time, though. Sometimes, we respond based on emotion9 or self-interests10 or because some decision feels right (all of these have reasons underlying them, but they may not be consciously derived). After the fact, we may then attempt to justify the actions we took.

In the case of the laptop story, it’s unclear whether the logic preceded the action (a priori) or was derived after the fact (post-hoc). In any event, the existence of the logic, coupled with the issues surrounding error management I mentioned earlier, may explain why the decision to censor the story was not easily overturned. It created a status quo that would require sufficient justification to conclude the decision was made in error (i.e., that the story was not, in fact, based on hacked materials).

The takeaways: (1) We can reason our way into a lot of decisions that turn out to be flawed. (2) Once we do, it can be difficult to reason our way out of that logic (which often leads to sunk-cost behavior).

The Big Takeaways

Although I dissected this one thread of the Twitter Files and provided a series of takeaways, what should also be evident is that all the issues I mentioned are interrelated. The presence of an ideological echo chamber made several of the resulting decision choices more likely. It served as the context or frame of reference within which the situation was interpreted, which values were activated, and how quickly Twitter was able to correct a decision that turned out to be made in error.

But this is not unique to Twitter or even other companies that are affectionately referred to as Big Tech. Based upon this first installment of Twitter files, there does not appear to have been some malevolent strategy in place at Twitter to help Biden win the election (at least not as evidenced by what I’ve seen). Instead, it may have simply been people within a company that exhibited evidence of strong ideological biases, and those biases influenced how they interpreted the world around them. As I mentioned in my last post, data can be used to tell many stories, and our frame of reference tends to influence which data we use and which story we tell. And, often, that story is subjective.

References

1. Editors don’t really appreciate when my word counts far exceed their maximum requirements.

2. I explained here how biases like this can result.

3. This is something I wrote on when discussing our internal predictive algorithms.

4. This is an issue my colleagues and I recently showed in series of studies.

5. Something I discussed both here and here.

6. Reasonable people can, of course, debate which consequences were truly worse, as mentioned in an exchange between Congressman Ro Khanna and a senior Twitter executive.

7. This is an issue I discussed here in reference to being a hypocrite online.

8. This is something I also wrote about here.

9. I wrote about the issue of emotions and motivated reasoning here.

10. I wrote about this issue as it concerns online behavior here.