The Surprising Power of Your Social Circles

Everyone needs to feel significant to someone.

By Psychology Today Contributors published November 7, 2023 - last reviewed on December 4, 2023

The Surprising Strength Of “Weak” Social Ties

By Gina Simmons Schneider, Ph.D.

A client, whom I’ll call Claire, lived alone for many years after a divorce. Her family was out of state, and she described feeling quite lonely, especially during the holidays. I asked her what helped cheer her up. “I love going to the library every week. My favorite librarian, Maria, chats with me about great historical fiction or cozy mysteries. I always leave feeling a warm connection with her.”

Another client, whom I’ll call Sherry, gets great joy from her Sunday breakfasts at a local diner. “I feel uplifted. The manager is so nice, and my favorite waitress calls me ‘Sweetie’ and brings me extra whipped cream for my pancakes. It’s my church,” she said.

As for me, when I shop for groceries each week, I prefer the checkout line with Judy, a cashier I’ve chatted with for years. We commiserate over body aches and wish each other happy holidays. Our shared kindness and familiarity offer me a sense of community.

Harvard researcher Hanne Collins has studied relationships like these, generally referred to as “weak social ties,” and found they can prove just as important to life satisfaction as core, or “strong,” ties.

It’s long been known that a community of supportive relationships improves our quality of life and can even help us recover from illness and surgery. Collins discovered something new: Regularly interacting with a wide variety of social ties, both weak and strong, fortifies our satisfaction, and a rich diversity of ties provides more significant benefits to well-being. So notice, pay attention to, and be grateful for your big, wide world of loose social ties: the people who cheer, serve, support, comfort, educate, motivate, and entertain you.

Even those we meet only once can leave a lasting impression. I remember discussing Anna Karenina on an airplane with a wise economics professor, finding meaningful moments of joy with street musicians and performers, and being cheered up by a man years ago when I worked in customer service. A rude customer in line right before him had shaken me. He noticed my distress and put me at ease with kindness.

All of those connections matter—and so do you. When you show kindness to a stranger, your seemingly small act might endure in their memory as a source of support and positivity. Everyone needs to feel significant in the eyes of another. You could be that person for someone in your extended circle, which is why it’s so important to reach out to people you care about, especially when they’re going through hard times—and to let those who care about you be there for you as well.

When we feel blue or lonely, we tend to turn down social engagements, either to avoid the imagined embarrassment of being the only sad person in a group or because socializing with people we don’t know well can be awkward at first. But saying yes, despite the hesitation, offers an opportunity to feel less lonely. Being open to both our strong and weak ties allows us to benefit from the comfort, connection, and community they provide.

Gina Simmons Schneider, Ph.D., is a licensed psychotherapist and the author of Frazzlebrain.

Do Your Friends Like Your Partner? You Should Hope They Do

By Wendy Patrick, J.D., Ph.D.

Bringing a new partner into your social network firms up relational bonds and ensures the presence of a support system that can serve as an objective sounding board for discussing potential conflicts. But such integration is more complicated when you’re dating someone on and off, particularly if that roller-coaster romance leaves you emotionally spent.

Are our friends more tolerant of our rockier romantic relationships? Not always. When you invite your on-again-off-again partner to a holiday dinner, don’t expect the same warm reception that they received on their first introduction. There may be a point when a friend or relative conveys resistance to hearing repeated complaints about the same partner and, verbally or nonverbally, suggests that it’s time for you to move on.

New research suggests a lack of friendly support for less-than-stable romantic relationships can have a surprisingly significant influence on their demise.

Concerns About Your Match

Family members and good friends are invested in your health and happiness and, by extension, the fitness of your relationships. They are thrilled to see you with a “good match” who brings out the best in you and will cheer both of you on as you step into the future together. When friends and relatives disapprove of your relational choices, however, they are much less inclined to offer unconditional support.

Research led by René Dailey of the University of Texas corroborates this experience. The team examined friend support from the perspective of the friend who was most familiar with the romantic relationship. They reasoned that friends are likely to have a higher degree of contact with both partners in a dating relationship than family members, particularly among younger adults. In addition, they note, friends can actually be better predictors of a relationship’s stability than the dating partners themselves—and dating relationships may have a larger impact on friendships than on family connections because a lack of support for a dating relationship could lead to the end of a friendship.

Prior research had suggested that partners in on-off relationships perceived less approval from friends and family as compared with steadier couples and that approval decreased as relational renewals increased. Dailey’s team surmised that perhaps friends and family of couples in on-off relationships become increasingly pessimistic about the sustainability of a connection that continually needed to be renewed.

In addition, concerned friends and family members might become more circumspect in supporting a friend in an on-off partnership and may just prefer a permanent end to the romance. Dailey’s team found that partners in on-off dating relationships reported less support from friends than did non-cyclical partners.

Introducing a romantic interest to family and friends can be flattering to your partner; it’s a step that often advances and deepens a relationship. But friendships and family connections will likely outlive unstable romances, and if they’re looking out for you, their subtle influence may speed a breakup. n

Wendy Patrick, J.D., Ph.D., is a trial attorney, behavioral analyst, and the author of Red Flags.

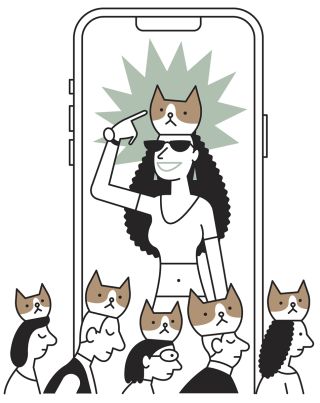

How Influencers Actually Influence You

By Richard Dancsi, M.Sc.

Online social networks provide a platform upon which influence can be created out of thin air. Psychologist Robert Cialdini’s bedrock principles of influence, outlined in 1984, are all at play on these networks. See, for example, how successful influencers share engaging stories that resonate with an audience. Frequent postings and interactions help make influencers more relatable to fans and give followers a sense of intimacy. Many influencers also manage to establish themselves as experts or authorities within their niches, even without the accreditation or gravitas of trained researchers.

Parasocial Love

Man is by nature a social animal, as Aristotle pointed out, but we’re not especially picky about how real our connections are. People routinely form “parasocial” relationships, feeling a deep emotional connection to someone without any direct interaction. We feel as if we know our favorite movie stars personally, and when the voice of a podcaster fills a room, we feel less alone. We recognize familiar faces, both on the internet and on the street, and form a sense of attachment to people we’ve never met.

Decades ago, the medium of television ramped up parasocial relationships by bringing the faces of popular personalities into people’s living rooms. In a 1956 paper, sociologists Donald Horton and Richard Wohl referred to this phenomenon as “intimacy at a distance.” The influence of parasocial connections has only increased as online platforms have emerged. “Technology proposes itself as the architect of our intimacies,” sociologist Sherry Turkle suggested in her book Alone Together, in which she explored how technology can both shape and replace face-to-face interaction.

As work becomes more remote and more of our real-life interactions shift to the cloud, the distinction between “real” and “virtual” has become less clear, creating an opportunity for canny online personalities who seek to become as familiar to us, and as influential, as our closest friends.

Selling Points

Marketers have long understood that friends and role models can significantly influence our buying decisions; companies have asked famous people to endorse products since at least the 1920s, but who actually qualifies as a “celebrity” has changed since the rise of reality TV, YouTube, and Instagram. It’s harder to dismiss the notion that online influencers, with instant access to millions, are now our truest celebrities. No wonder major brands seek them out for endorsements.

Many influencers began their careers as amateur social-media users and have learned the hard way that publicity and fame are double-edged swords: Do it well and you can become an opinion leader for a community of such size and strength that you cannot be ignored. Do it wrong and you can become a public enemy.

As for us users, it’s important to understand who’s really influencing us when we make purchasing decisions. Some estimates suggest that social-media endorsements help sell $2 billion worth of products a year, giving influencers plenty of incentive to continue blurring the line between friend and marketer.

It was once suggested that, at our core, we are the average of our five closest friends, but today, as the parasocial pushes out the face-to-face, we may be more the average of our five closest influencers.

Richard Dancsi, M.Sc., is an entrepreneur and consultant.

Why Your Childhood Sibling Dynamic Can Re-Emerge in Your Adult Relationships

By Karen Gail Lewis, LMFT

After 10 years of marriage, Meka and Neelu* sought therapy. It was their third attempt to save a relationship both said they had no intention of leaving.

Their most recent battle was about Meka using marijuana in the house. Neelu said she was OK with Meka’s smoking, but also repeatedly asked, “Do you really want your kids to see this?” only to have Meka respond, “You always try to control me; you can’t tell me what to do!”

Their previous couples therapy experiences had focused on similar control issues, but since they had been largely unsuccessful, there seemed no point in repeating what had already been tried. Instead, I decided to look for a sibling transference in their relationship.

Early childhood is our first experience of living intimately with peers—people on the same hierarchal level and of the same generation. To understand the influences of the early sibling dynamic, both subtle and overt, on adult relationships, let’s think about what young children learn from their siblings.

In the first 6 to 10 years of life, children learn—or don’t learn—skills for fighting and resolving fights, for competing and saving face. They learn—or don’t learn—when to exert their power and when to withdraw. And when there is a physical power imbalance, they learn how to draw on other skills, such as humor, manipulation, tattling, and blackmail.

Later, as adults, when in conflict with a loved one, they can, without conscious awareness, transfer what they learned in childhood. This transference can be triggered by as little as someone’s look or facial expression. For example, a woman might experience an expression made by a partner, friend, or boss as affectionate, reminding her of her warm feelings she once held for a sibling.

How erroneous can transferences be? Well, perhaps the expression she saw as affection was the other person stifling a gas pain. Or, influenced by a negative relationship with a sibling, she might react to the same look (generated by gas) as if she were being regarded as stupid. Or the same look might make her feel fearful.

I worked with Meka and Neelu on exploring their early sibling relationships. I asked each if they’d ever had the same feelings when they were little. Meka immediately replied, “My big brother was a goody-two-shoes; he was always telling me what I could or couldn’t do.” I pointed out she had made the same complaint, in almost the same words, about Neelu.

Neelu’s sister was developmentally disabled, and she grew up “constantly hearing it was my job to take care of her.” So, while Meka’s experience had been fighting a control battle with her brother, Neelu’s was always feeling responsible for a less fortunate sibling. Each appeared to have transferred those childhood experiences to their marriage. If we hadn’t talked about these early sibling relationships, they might never have discovered the roots of their conflict pattern.

As with many other clients, even when these partners were able to see and understand how they re-created these patterns, they struggled to break them. Therapists can help people listen for clues to a sibling transference—when they use the same words about a sibling as they do a partner or when they find themselves quickly overreacting in a conflict.

Sometimes, I or a client will suggest meeting with a sibling to resolve old hurts or resentments. But even without that step, clients can learn to notice when they are reacting in a relationship as they did in their “first marriage” and, with work, move past those reflexive responses and chart a fresh path together.

*Clients’ names have been changed to protect their privacy.

Karen Gail Lewis, LMFT, is a family therapist and the author of Sibling Therapy: The Ghosts From Childhood That Haunt Your Clients’ Love and Work.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of this issue.

Facebook image: Look Studio/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: oneinchpunch/Shutterstock