The Power of Boundaries

Sharing personal information brings people together and helps them like one another more. But in an age of self-disclosure, how do you know when you’ve gone too far—or when someone else has ulterior motives?

By Sara Eckel published October 14, 2019 - last reviewed on January 14, 2020

When Tom Kealy signed up for a day-long personal essay writing workshop in Berlin, the data scientist saw it as an engaging way to fill a Saturday. “I thought it would be good fun—trying interesting exercises, learning how to make something out of your experiences,” he says.

Then his classmates went around the table to share what they’d be discussing: a racist father, an S&M relationship gone bad, an abusive boyfriend. Kealy, slated to be the 14th of 15 in the group to speak, had planned to write about learning to draw. “By the time it got to me, I realized this was not the class I’d signed up for. As the day went on, I increasingly felt, Oh my God, this is way too much.”

One could argue that in a personal-essay class, each participant should be prepared for whatever topic arises, and Kealy suspects he was just unlucky that the subject matter in this particular cohort was so dark. But his gut reaction—whoa, TMI!—is one many of us know well.

We live in a time of unparalleled personal expression. Long-lost co-workers and high school acquaintances daily invite us into their homes and their psyches. Traditionally marginalized groups are speaking out. Victims are confronting abusers. Addicts are owning their pasts. The freedom to “speak your truth” and “give zero f*cks” brings a lot of benefits, but it can also lead to some thorny questions, like how much we should reveal about ourselves—and how much we should want to know about others.

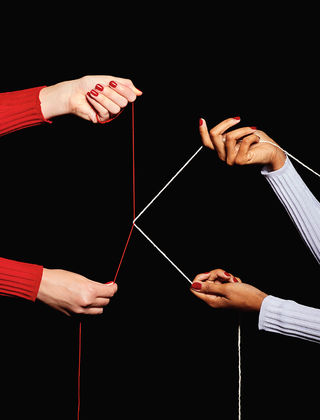

Each of us tries to erect a boundary around the parts of ourself we want to keep private, or at least shielded from those with whom we’re not intimate. Some people are more vigilant about raising those firewalls than others, however, which can lead to discomfort, if not open conflict, because it’s harder to keep others’ revelations out than it is to keep our own within. “We think about boundaries as a self-oriented concept: This is my boundary. But it’s not just a matter of what you’re willing or not willing to say, it’s also what you’re willing to let in,” says Mariana Bockarova, a psychology researcher at the University of Toronto.

In healthy relationships, romantic or otherwise, Bockarova says, we attune ourselves to others’ boundaries by making gradual “bids of trust.” For example, on a first date you might confess that you’d had a tough day at work because your boss was snippy to you. “If the other person doesn’t say anything back, chances are you wouldn’t further extend,” she says. “Bids of trust are lessened when there’s no reciprocity. You’re suddenly not safe with this person.”

...If You Show Me Yours

Sitting in that class of 15, Kealy’s distressed silence didn’t register the way it would have if he had been with only one or two people. It was easier to just stay quiet and keep his discomfort to himself. But even one-on-one, people aren’t always receptive to cues—averted eyes, frantic smiles—that now is not the time to discuss their digestive-tract issues or custody battles.

Here’s the rub: We like telling others about ourselves. In research conducted by Illinois State University sociologist Susan Sprecher, previously unacquainted participants were paired and instructed to ask each other questions. In one group, people took turns—one person spoke for 10 minutes while the partner listened, then they’d switch. In the second group, individuals engaged in a reciprocal back and forth, responding to each other in the moment. In the reciprocal version, confidantes liked each other more.

When we are first getting to know one another, Sprecher explains, we find the encounter most enjoyable when the extent of self-disclosure is balanced. On a first date, the guy who talks nonstop about himself may be an unappealing candidate, but, then, so is the woman who only asks questions and never shares anything.

That natural inclination to reciprocate can backfire, however. Angela J. Thompson was initially happy to meet a woman named Sarah at a Chamber of Commerce event in Jacksonville, Florida. Both had gone through contentious divorces with abusive men who had cheated on them; Sarah knew this about Thompson because she had published an account of her ordeal in an anthology about women rebounding from setbacks. Thompson was, in fact, doing well by that time and running an asset-management company. She was glad to have an opportunity to share her advice and experience, but then Sarah started grilling her with questions like, “Do you think your husband cheated because you gained weight?” and “How often did you have sex?”

Shocked in the moment, Thompson says, she answered her. “It was almost over before I really started questioning myself,” she says. “I just wasn’t prepared.”

People who score high in the personality trait of agreeableness are particularly susceptible to this type of boundary blindsiding, Bockarova says. “They’re more likely to accept someone oversharing and to share in response because they don’t want the other person to feel in the wrong.”

For those so inclined, Bockarova recommends practicing the skill of being just a bit disagreeable—allowing an awkward silence to hang for a few moments or declining to answer a prying question. This not only protects your privacy, but enables you to get some important information about other people. “If their reaction is not particularly kind, that will teach you something about whether you can engage in difficult conversations with them. If they validate your feelings and apologize, you’d be more likely to trust them,” she says.

Danielle Bayard Jackson, for example, has close female friends, but would sometimes feel uncomfortable when talk turned to their sex lives. “They might gab about it or make a joke. They’ll divulge and ask questions about me and my husband—not to be nosy, but because we’ve had a glass of wine,” she says. “So I’ve learned to just say, ‘Girl, I’ll talk to you about a lot of things, but for some reason I protect that. That’s just my thing.’”

By making her need for privacy “her thing,” Jackson keeps the conversation from devolving into shame or blame. “If you say, ‘I’m sorry, but that makes me really uncomfortable,’ you’ve created an awkward situation where they’re scrambling to recover. But if I say, ‘I love you, but I just don’t talk about that,’ that can actually create an interesting conversation,” says Jackson, co-founder of a Tampa public relations firm for underrepresented groups.

Dreading the Office

During her earlier career as a high school teacher, Jackson had a co-worker who talked at her incessantly. While Jackson tried to grade papers or schedule calls with parents in the teachers’ lounge, the colleague yammered on, griping about students and the principal. Jackson knew better than to share her own work-related frustrations with such an indiscreet talker, but she also wasn’t comfortable confronting her. “I felt like I had to listen to her because everyone else shunned her; she didn’t have anyone else to talk to,” she says. “I chose to be polite and to just dread going to work every day because I was too worried about the fallout from saying something.”

The problem bled into her home life, where her boyfriend was subject to nightly rants about the co-worker. “I was possessed,” she says. “It was all I wanted to talk about when I got home.”

Jody Foster, a psychiatry professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, says that letting the office oversharer dump on you isn’t just detrimental to your productivity and mental well-being; it can also put you in a difficult position if someone is truly unstable, “and then you realize, Oh no, this is my responsibility.”

Simply telling a colleague that she’s out of bounds isn’t always an option, since offending her could make your work life even more difficult. In that case, says Foster, co-author of The Schmuck in My Office: How to Deal Effectively With Difficult People at Work, consider putting a timer on the monologues. That’s what Jackson eventually did. “I learned to say, ‘I’m so sorry. I have to make these calls right now. Can we chat about this after school?’ Then I’d dedicate five minutes. After that, I’d say ‘I guess I should get going. I have papers to grade.’”

Jackson believes her former co-worker was just needy, but sometimes colleagues have more insidious motives. They might want to push you to divulge your own grievances about the boss so they can one day use the information against you. Or they might be priming to dump their work on you, teeing up sympathy with sob stories about backaches and bad partners. The most dangerous of these people have the “dark triad” personality traits associated with ethically and morally questionable behavior—narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism. A 2018 Danish-German project found that a common denominator of these traits is a proclivity to prioritize one’s own interests over the needs of others, even if it means causing harm to them.

To protect yourself, Foster advises, observe seemingly problematic co-workers’ behavior over a significant period of time before offering your trust. Pay attention to who speaks over their colleagues in meetings, who takes credit for the group’s work, and who always peddles the most salacious gossip. “People are always giving you little tips of their iceberg,” she says.

And when you’re the boss, you’re likely to notice that some employees will strive to break down boundaries for their own benefit. “They want to draw you in so they can get past those barriers,” says Dane Kolbaba, an entrepreneur whose companies include an ecofriendly pest-control firm in Phoenix. “But then you’re not the boss anymore. You’re just Dane, ‘my buddy,’ And with buddies you get special favors.”

In and out of the office, relationships change over time. College roommates fade to distant acquaintances while new neighbors become best friends and strangers become spouses. As we develop and step away from intimacy with others, the rules of engagement constantly shift.

When Guys Open Up

During the initial, getting-to-know-you phase of a relationship, we engage in reciprocal sharing, but Sprecher says that as healthy relationships develop, we stop adhering to the straight tit for tat. “If you’re on a fifth date and you had a really bad day and want to vent, you wouldn’t necessarily want the other person to say, ‘Okay, my turn. I want to talk about my horrible thing.’ At the very beginning, reciprocity might be extremely important; later, the responsiveness of your partner is more important.”

As relationships progress, pairs discuss fewer topics but go deeper. The disclosure timetable, however, can vary greatly. For most of their 20-year friendship, Riz Rashdi and his two best friends never got very personal in their conversations. “We’d talk about sports, their kids, what we did last weekend, surface-level stuff,” says Rashdi, a San Diego business analyst.

But when his marriage ended after 14 years, Rashdi wanted to know about his friends’ experiences, since they had gone through divorces, too. Were they sad? What did they do with their ex-wives’ stuff? Was it still in the bedroom when dates came over? “We got so much closer because I opened up. For them, it was stuff that had already happened three or four years earlier, but we’d never talked about it because we’re guys and we don’t feel we need to. But once we opened the door, it was awesome. I thought, Is this what it’s like being a woman—where you get to connect this much with another person?”

Rashdi’s instincts are correct: Women tend to reveal more of their emotional lives to one another than men do. “Men tend to socialize with activity-based experiences, whether it’s going fishing or watching sports together,” Bockarova says. “They’re less likely to have heart-to-hearts where they spend a really long time talking about their problems.”

Instead, many men rely on their romantic partners to receive all of their deepest fears and traumas—a phenomemon that has been dubbed “emotional gold-digging.”

“Wives tend to be better than husbands at maintaining intimate relationships beyond the marriage,” says Northwestern University psychologist Eli Finkel, “which means that husbands are highly dependent on their wives for emotional connection.”

Finkel’s research has found that Americans place significantly higher emotional demands on their marriages than they did in decades past, a problem exacerbated by the intensity of 21st-century life. Increased expectations for workers and parents, combined with an unending stream of digital information, leaves spouses with less bandwidth to meet their partner’s needs. Finkel recommends that spouses—especially husbands—maintain a wide circle of friends and family members with whom they can share their interior lives.

In other words, yes, reveal your most private self to your spouse, but remember that partners have to maintain boundaries, too, and might not always have the emotional capacity to revisit your difficult upbringing or fear of death.

When the time is right, sharing vulnerabilities with partners increases intimacy, but only under certain conditions. Chandra Khalifian, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, noticed that the vulnerabilities couples brought into therapy concerned issues that occurred within the relationship—complaints like “You don’t treat me as an equal.” However, the bulk of the research she’d seen centered on the effects on relationships of external difficulties partners had experienced before they met, like a bad divorce or a traumatic childhood.

So Khalifian conducted research separating “partner-exclusive” and “partner-inclusive” vulnerabilities. While her work affirmed that partner-exclusive vulnerabilities increased intimacy, partner-inclusive ones actually created more distance. For example, one man in the study said he felt embarrassed when his partner made fun of him in front of their friends, violating a boundary he expected her to maintain: “Even though you think it’s just a joke, it makes me not trust what you say in public, so I don’t want to spend time with you around our friends.” In this dynamic, Khalifian says, the partner who caused the emotional pain feels implicated and is likely to respond defensively since she is motivated to reduce her own distress first, not comfort her partner.

When we relate to each other in person, the impulse to alternate disclosures and bids of trust keeps most of us within bounds. But all of that goes out the window when we’re relating to each other online. Without one-on-one social cues, it’s easy to become careless with what we reveal about ourselves—and others. And then it’s Tom Kealy’s oversharing writing class, times a billion.

Moms on Facebook

Jennifer Golbeck, a computer scientist at the University of Maryland, says social media create a disconnect between the audience we think we have—the friends whose posts we follow and like—and the people actually watching us; studies by Facebook find that users estimate that their audience is only about 27 percent of its actual size. “Even though we know the information is semi-public, we think we’re talking to just a certain group of people,” Golbeck says. “We’re lulled into thinking we have a friendly audience when we don’t necessarily.”

That cognitive dissonance is intentional, says Leah Plunkett, a professor at the University of New Hampshire School of Law and the author of Sharenthood: Why We Should Think Before We Talk About Our Kids Online. Technology companies don’t actually intend for us to experience their platforms as public spaces, she says. “They want us to experience them as extensions of ourselves and our homes.” That’s why she, like Golbeck, recommends putting our 21st-century behavior in a 20th-century context—an exercise she believes is particularly useful for parents. “If your parents had said, ‘Oh honey, we just rented a billboard on the highway to let everyone know you’re finally potty-trained,’ that would have been weird,” she says.

For the past several years, photographer Amber Faust has posted countless pictures of her kids online—with more than 230,000 followers, her 3- and 4- year old sons are Instagram stars. But a few years ago, her 13-year-old daughter got fed up. She’d go to school ready to show friends her new haircut, only to find that they’d already seen it on Instagram—on her mother’s feed. Or her classmates would know she was getting braces—before she did. “She’d come home and say, ‘Mom, what are you saying on Facebook?’” Faust admits.

Faust realized she needed to cool it. She still liberally posts pictures of her boys, but her daughter has asserted veto power. “She’ll say, ‘Mom, this one’s not for Instagram, but you can keep it on your phone.’ I messed up a few times, but I’m respecting it now,” says Faust. She notes that her daughter’s own Instagram page is dedicated solely to her digital artwork, “which is crazy to me. She’s got all these gorgeous pictures of herself.”

Ask your average Baby Boomer or Gen Xer, and they will likely attribute the decline of digital boundaries to those kids today who can’t keep their private information private. But Golbeck says the cohort of parents over 40 confuses generational differences with youthful indiscretion. “If there had been Facebook in the late sixties, you cannot tell me that Summer of Love would have not been a trending hashtag. We’d have seen pictures of topless hippies with flower crowns all over the Internet. So when Baby Boomers say, ‘I’ve always been very protective,’ that is just nonsense. They absolutely would have been posting that stuff,” she says.

What’s more, says Golbeck, younger people have been found to use more privacy controls than their elders do and to migrate toward platforms like Snapchat where posts are quickly and automatically deleted. And, like Faust’s daughter, many young people who grew up with their milestones, awkward and otherwise, involuntarily splashed across their parents’ social media feeds are now coming of age and taking control of their images.

The problem isn’t limited to adorable first-day-of-school pictures. Even those of us who aren’t posting our memoirs and vacation documentaries probably reveal more than we realize. In one study, researchers analyzed only the things that Facebook users liked and found that, with varying levels of accuracy, they could predict the user’s political party or drinking habits and whether their parents divorced before they turned 21. As data analytics become more sophisticated, Golbeck says, all those thumbs-up icons have the potential to greatly affect our futures should the information land in the hands of insurance companies, banks, university admissions officers, and prospective employers. She’s not suggesting people go off the grid, but that they research and use plug-ins to cleanse accounts after a few weeks’ time. Her exception: The Instagram feed of her five golden retrievers, which will remain intact in perpetuity.

When Parents Come Clean

Rather than sharing with others about their kids, and potentially violating their adolescent boundaries, psychologist Carl Pickhardt believes parents would do better to take down their own shields and share with their kids. “Sometimes an 18-year-old comes in for counseling and I’ll ask him to tell me about his parents. The kid will just look at me and say, ‘There’s not much I can tell you. All we ever talk about is me,’” says Pickhardt, the author of Who Stole My Child?: Parenting Through the Four Stages of Adolescence.

Some parents worry that revealing past misdeeds to their kids amounts to tacit permission to engage in bad behavior, but Pickhardt says talking about the time mom or dad got slurring drunk or crashed the family car can help kids learn from adult mistakes. “Parents are a well of personal experience—if they will allow their adolescents to know them,” he says.

Of course, parents should exercise some restraint. If a father is going through serious emotional distress, he shouldn’t look to his teenage son or daughter for emotional support. At the same time, though, the adults might need to disclose that something is up, since the kids likely sense it anyway. Pickhardt recommends saying, “Yeah, there is some stuff going on, but I’m handling it. I’m going through kind of a hard emotional time, but I have somebody else I can talk to about it.”

Generally, though, offering older children a more complete and nuanced portrait of a parent can aid their development into adulthood. Such an exchange can help parents cultivate an adult relationship with their child in which all participants’ boundaries are honored. “If I’m not modeling for my kids that I respect their bath time and their nightmares,” Plunkett says, “then I have no reasonable basis to expect they’ll do the same for me.”

Here’s the central paradox of boundaries: We want to be known, and we also want to be safe. We crave both intimacy and protection. The luckiest of us find people we can have both with, but we are always in danger of blowing it up—of misplacing our trust or saying too much.

Fortunately, the complex, ever-shifting nature of our personal boundaries is also their strength. The lines in the sand will fade, but we can always redraw them.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the the rest of the latest issue.

Facebook image: Anna Kraynova/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: Lyubov Levitskaya/Shutterstock