When the Body Speaks

Psychosomatic illness is baffling to both patients and doctors. But it always happens for a reason: Sadness can be too impenetrable for words.

By Suzanne O'Sullivan M.D. published January 3, 2017 - last reviewed on September 7, 2019

Pauline, 25, had been admitted to the hospital with pain and swelling in her leg that no amount of morphine could quiet—her third admission for the same complaint. She had been in and out of hospitals for 12 years with an array of problems, and invasive tests had never yielded a definitive explanation. That morning, the team looking after her told her that they had exhausted all tests in the search for a cause, nothing further needed to be done, and she could go home.

One hour later Pauline had packed her bags and was in the bathroom when she lost consciousness. Once she was fully awake, she was carried back to her bed. But almost as soon as she got there, she felt the seizures begin again. No sooner had Pauline's mother arrived to take her home than a third convulsion struck. I met Pauline shortly after.

From an early stage in my medical training I knew that I wanted to be a neurologist. I enjoyed the detective drama of the job, unraveling the mysteries of how the nervous system communicates its messages and learning all the things that can go wrong. Neurological disease manifests in elusive and strange ways. When I started, I could not have predicted how far I would find myself drawn into the care of those whose illnesses originated not in the body but in the mind.

Modern society likes the idea that we can think ourselves better. When we are unwell, we tell ourselves that if we adopt a positive mental attitude we will have a better chance of recovery. I am sure that is correct. But society has not fully woken up to the frequency with which people do the opposite—unconsciously think themselves ill.

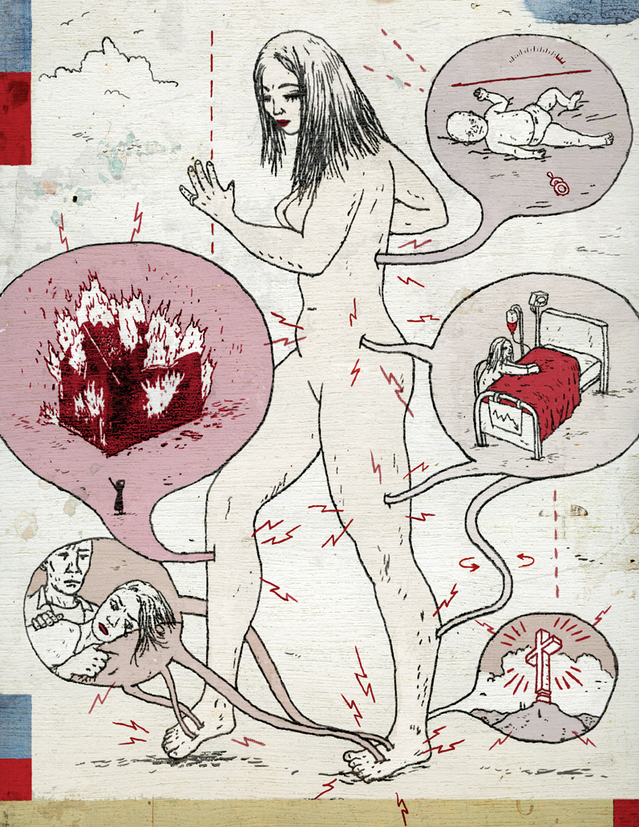

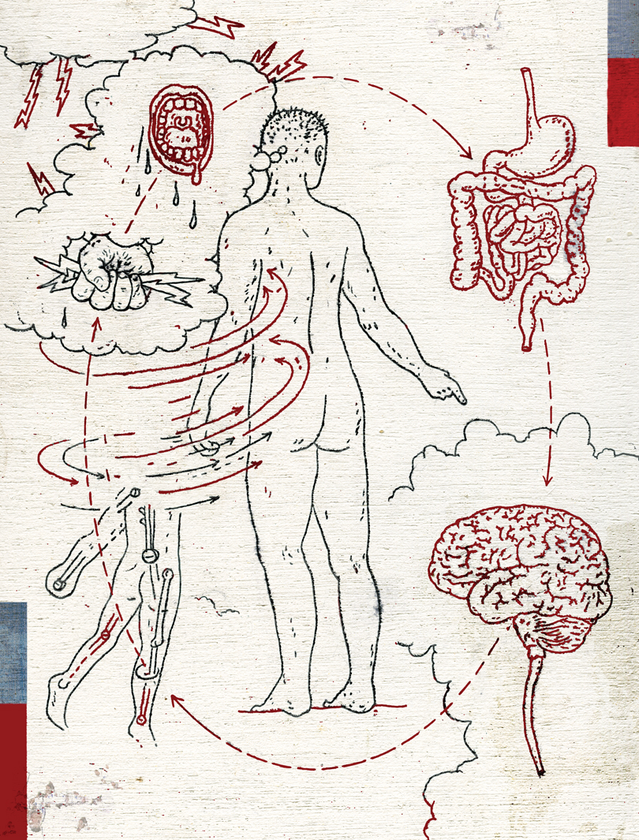

Psychosomatic disorders cause real distress and disability, but they are medical disorders like no others. They obey no rules. They can affect any part of the body. In one person they might cause pain. It is not unusual for somebody going through a period of stress to be troubled by palpitations. Psychosomatic illness can also manifest in ways that are more extreme but less common, such as paralysis or convulsions. Almost any symptom we can imagine can become real when we are in distress—tremor, fatigue, speech impairments, numbness. Anything.

On any average day perhaps as many as a third of people who go to see their general practitioner have symptoms that are deemed medically unexplained. Of course, a medically unexplained symptom is not necessarily psychosomatic. There will always be diseases that stretch the limits of scientific knowledge. But among those with undiagnosed physical symptoms is a large group in whom no disease is found because there is no disease to find. In those people the medically unexplained symptoms are present, wholly or partially, for psychological or behavioral reasons.

Psychosomatic disorders are physical symptoms that mask emotional distress. The very nature of the physical presentation of the symptoms hides the distress at its root, so it is natural that those affected seek a medical disease to explain their suffering. They turn to medical doctors, not to psychiatrists, to provide a diagnosis. The neurologist is more often faced with a diagnosis of psychosomatic illness than other specialists.

I have met many people whose sadness is so overwhelming that they cannot bear to feel it. In its place they develop physical disabilities. Against all logic, people's subconscious selves choose to be crippled by convulsions or wheelchair dependence rather than experience the anguish that exists inside them. I have found myself astounded by the degree of disability that can arise as a result of psychosomatic illness. I have come to realize that these disabilities can serve a very important purpose. They happen for a reason. When words are not available, our bodies sometimes speak for us—and we have to listen.

A Case of Seizures

There is only one way of knowing with confidence why a person has lost consciousness, and that is to witness the event. Sometimes blackouts have a trigger. In epilepsy it might be flashing lights or sleep deprivation. Where triggers are not clear, video telemetry units are invaluable.

In a video telemetry unit, patients are restricted to a room where they are under constant video surveillance while electrodes attached to their head make a round-the-clock recording of their brain wave, or EEG, pattern. The electrical activity of the brain reveals whether a person is awake or asleep, conscious or unconscious, at any given time. An EEG is the definitive means of assessing consciousness and is one of the primary tools in understanding why a person has suffered loss of consciousness. When a convulsion occurs, the nurse is ready to run into the room to assess the patient and keep him or her safe and reassured until recovery.

If a healthy person faints because of dehydration or overheating, the first physiological change is a fall in blood pressure. The heart detects the problem and tries to compensate with an increase in heart rate. If the increased heart rate is not enough to compensate for the dropping blood pressure, then just for a moment, vital blood is drawn away from the brain. As the brain becomes deprived of oxygen, the brain waves slow dramatically and the patient loses consciousness.

The cause of a blackout might lie not in the heart or blood pressure but in the brain itself, which is the case in diseases like epilepsy, and the sequence of physiological events is different. Each pattern of events, along with a video of the collapse, suggests a specific diagnosis that is usually reliable. The overarching principle on which each diagnosis rests is always that you cannot be unconscious—neither asleep, nor anesthetized, nor in a seizure—if your brain waves do not change. At my suggestion, Pauline was assigned to the video telemetry unit.

"I have reviewed each of your seizures carefully," I told Pauline later. "The first piece of good news is that I have not seen the pattern that I expect in an epileptic seizure; you definitely do not suffer from epilepsy. The heart tracing is normal, so the heart looks healthy, also a relief.

"When I looked at the brain waves during your seizures, I saw that they showed the pattern I might expect in somebody who is conscious—a waking pattern. The brain wave pattern looked normal, and there is only one reason that people can be unconscious—completely unaware of their surroundings—with the brain waves still looking normal. And that is if the loss of consciousness is caused by something psychological rather than by a physical brain disease."

"Are you saying I'm making this up?"

"No, Pauline, I know your seizures are real. But they are arising in the subconscious rather than being due to a brain disease. One extreme way that the body can respond to upset is to undergo a blackout and convulsions. This sort of convulsion is known as a dissociative seizure. Dissociation means that a sort of split has occurred in the mind. Your conscious mind separates from what is happening around you. That detachment means that one part of you doesn't know what the other is doing. But it's not deliberate. You cannot make yourself unconscious any more than I can deliberately blush or produce tears. These seizures are your body telling you that something is wrong. A psychiatrist might help you work out what that is. I think that these seizures are curable, Pauline."

Physical manifestations of unhappiness are something we all experience; they are not personality flaws or signs of weakness, they are a part of life. Life is hard sometimes. It is harder for some than for others. We all manifest hardship in different ways: Some cry, some complain, some sleep, some stop sleeping, some drink, some eat, some get angry, and some suffer like Pauline.

Presenting with Paralysis

In the legal system, the burden of proof requires evidence to support the truth. But in the case of psychosomatic disorders the diagnosis most often rests on the lack of evidence. The diagnosis is made when disease is not found. Every week I tell people that their disability has a psychological cause. When they ask me how I have come to that conclusion, all I can provide is a list of normal test results, evidence for ruling out diseases. When a person is paralyzed or blind or suffering from convulsions, it is not difficult to see why that finding is very unsatisfactory.

"I am completely sure you do not have multiple sclerosis," I told Matthew.

"How sure are you?"

"All of the tests are negative."

"What percentage are you sure?"

"I am absolutely sure."

"You can't be 100 percent sure. Nothing is ever 100 percent."

Matthew was a product of the Internet age. When he came to me, his research had utterly convinced him that he had multiple sclerosis. Matthew's problem began with a sensation of pins and needles in one foot. Sitting at his computer in his office, he would feel the tingling and need to stand and move around to make it go away. In the evenings it would go, but the next working day it was always back.

After nearly two weeks, Matthew went to see his doctor and was assured that such symptoms are common and rarely mean anything worrying. Matthew was not satisfied. He took it upon himself to research the possibilities. The Internet advised him that diabetes could damage nerves and lead to pins and needles. Matthew stopped eating sugary foods but got no better. Again he discussed his concern with his doctor, who told him that his blood sugar was normal and he did not have diabetes.

Matthew thought it possible that he might have poor circulation and exercise would correct it. When it did not, he tested the effect of avoiding exercise and resting as much as possible. The patches of numbness spread to his trunk.

By that point he was finding it difficult to work. Sitting for prolonged periods was impossible. Matthew began to work from home. At the same time he intensified his research. That was when he discovered that multiple sclerosis could cause sensory abnormalities that moved around the body. With everything new he learned, his symptoms began to evolve. He noticed pain and loss of balance if he walked any distance. He began to feel dizzy. Tiredness overwhelmed him.

One day Matthew awoke to find that he had lost all strength in his legs. His wife called an ambulance, and he was taken to his local hospital. A scan of his spine and brain offered no explanation. A lumbar puncture, blood tests, and electrical studies of his nerves and muscles showed nothing wrong. Matthew was given a wheelchair and sent home.

A week later Matthew's wife wheeled her husband into my office. "I know I have multiple sclerosis," he began.

"Let's not jump to conclusions. For the moment just tell me how your symptoms started and how they evolved."

As I listened, I tried to spot an anatomical pattern that would explain everything, but what Matthew was describing was impossible. There was no part of the nervous system that, if diseased, could account for all that he described.

After Matthew had finished telling me his story, I asked to examine him. I tested the strength of his muscles one by one. A disease of the spine causes one distinct set of symptoms, a disease of the nerves another. Brain disorders cause certain groups of muscles to be weak while others are surprisingly strong. Matthew's pattern did not fit with any anatomical location.

But Matthew was more than his medical history and clinical examination; he was a person with a life beyond his illness, and in that life I saw other points of concern. Matthew worked in accounting and changed jobs regularly. What made him move on so often? Did moving protect him from something? Did illness do the same? Was he hiding?

A further MRI scan of his brain and spine, the standard test for MS, showed no white spots of inflammation. I set out to check the integrity of Matthew's nervous system. He underwent an electrical study of his nerves. And when the tests were completed, I met with him again.

"I know you are suffering, Matthew. But you do not have MS. The weakness in your legs doesn't fit with neurological disease. Such profound weakness should come with other clinical signs, altered reflexes, or wasted muscles."

"But it feels so real, it can't be nothing."

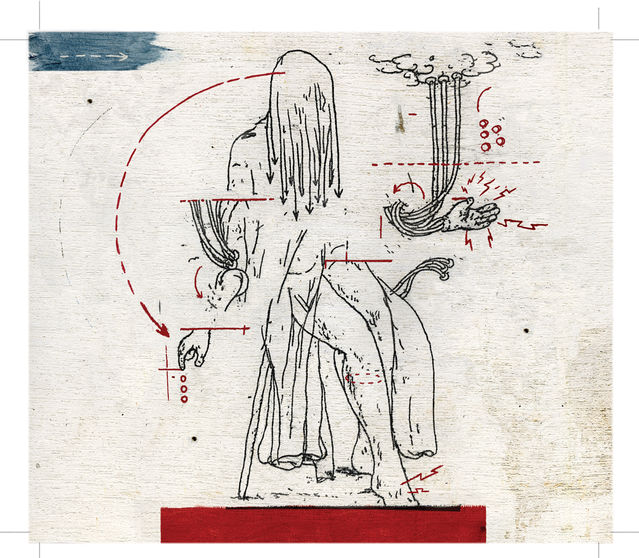

"It feels real because it is real." MRI studies of the brain firmly establish that there is something awry. When the brain activity of patients with psychosomatic paralysis is compared with the brain activity in those who are asked to pretend to be paralyzed, a very different pattern of brain activation appears—establishing without doubt that psychosomatic illness is not pretending. Patients with psychosomatic paralysis have lost the ability to recruit the necessary motor pathways to make paralyzed limbs move. This does not necessarily mean there is a disease present, but suggests the existence of a learned inability to move.

The nature of the disability is usually impenetrable to the sufferer. My patients struggle to accept the power of the mind over the body. They pursue a medical diagnosis and refuse to believe that no organic disease can be discovered.

"Your paralysis is not imagined," I told Matthew, "but that does not necessarily mean that it is a primarily physical disorder. There is some dysfunction in the way the message telling your legs to move is traveling from your brain to your legs. I don't know how that happens. I just know that it can happen and that it may help to see a psychiatrist."

There have been many advances in understanding biological disease, but progress to explain how emotions produce physical symptoms has been slow. We still have a limited grasp of how thoughts and ideas are generated; we are no closer to explaining imagination and no closer to understanding or proving the reality of illnesses that arise there.

In its close relationship with psychosomatic disorders, neurology has conferred on them its own name, "conversion disorders," as if the conversion of distress into paralysis or seizures instead of pain or fatigue is in some way special, when it is not (pain is by far the most common psychosomatic condition). Symptoms that arise through stress or anxiety are produced in the mind and are dependent on what the sufferer understands about the body and disease. Disabilities that arise in the subconscious rarely obey anatomical rules. It is just this rule breaking that makes conversion disorders so out of keeping with neurological disorders.

Telling patients that their disability has a psychological cause creates in them a feeling that they are being accused of lying, faking, or imagining their symptoms. For my patients to recover, I need them at least to consider a psychological cause for their illness and to agree to see a psychiatrist. Even when patients succeed in this, their families often don't. We live in a world where disability that occurs for psychological reasons is considered less legitimate than other forms of disability.

Six weeks later, I was greeted by a transformation. Somewhere in the time since we had last met, Matthew had been converted, or had converted himself, to the idea of a psychosomatic disorder.

"How did the meeting with the psychiatrist go?"

"The psychiatrist explained things a lot better than you did. He said the nervous system is like a computer: My hardware is intact, and the wires are all in the right place, but I have a software problem that keeps my legs from receiving the instruction to move."

Psychosomatic disorders are noteworthy for how little respect they have for any single part of the body. No bodily function is spared or ignored. And how easily these disorders flit from one place to another! Just as one symptom is discovered, it disappears, and another emerges somewhere else. The ancient Greeks thought that the uterus wandered about the body causing symptoms. But it is not an organ that wanders, it is sadness. And it is looking for a way out. Because my own hands shake when I am nervous, I can see logic in the notion that an emotion can be converted into a physical symptom.

Because psychosomatic symptoms arise in the subconscious, their manifestation depends on what else lives there. Our subconscious is filled with memories, with past experience of illness, what we know about the body, and what lessons life has taught us. That is what we draw on. Society, culture, and superstition plant ideas that mold our concerns about our bodies and that help to determine what counts as an acceptable public manifestation of distress.

There is no single solution to psychosomatic illness. To look for one is akin to looking for the cure for unhappiness. There is no single answer because there is no single cause. Sometimes you just have to figure out what purpose the illness serves, find what is missing, and try to replace it. If illness seems to be helping to solve the problem of loneliness, then treat the loneliness and the illness will disappear. Or find out where the gain lies and address that. Or if the problem lies in maladaptive responses to messages the body sends, that can be relearned: Break the patterns of fear and avoidance. Or if there is a specific trauma triggering illness, then address it.

We all somatize our emotions. Think about laughter. When we laugh our diaphragm contracts repeatedly, air is expelled from our lungs and then drawn back in again at speed. The larynx half-contracts and a rhythmic gasping sound is released. Facial muscles contract and the mouth opens. The skin around the eyes wrinkles. The head goes back. Sometimes the whole body joins in; the hands clutch the stomach, we bend forward at the middle, and our whole body trembles. When the pleasurable emotion goes far enough, water gathers in our tear ducts and releases itself. For a second we can barely breathe, our hearts race, and our faces redden. And it is contagious. The heartier the laugh, the more people around us look at us and join in.

But laughter communicates more than just mirth; it can be triggered by social discomfort or embarrassment, or it can be an expression of negative intent, such as derision. In most cases laughter is involuntary, but it can be faked.

Nobody fully understands the mechanism by which the brain produces laughter. It's likely that laughter is not a single phenomenon, that different laughs have different causes and are generated in different parts of the brain. That is why a laugh of derision is not easily mistaken for one that is heartfelt; they are related but different phenomena.

It was long believed that laughter, like dreams, could betray our secret thoughts. Most of us have laughed when we didn't mean to and so inadvertently allowed people to know something of what we thought. Jokes let us laugh at things that are not socially acceptable, and that in itself is revealing.

Laughter can be therapeutic. Pent-up anger or sadness can be converted to laughter, which releases internal tension. Laughter can distract us. If we are suffering from stress or fear, we might suppress or deny it and seek out laughter instead.

And laughter can go wrong. Sometimes it can be a sign of illness or disease. Inappropriate, poorly controlled laughter is seen in a variety of psychiatric and neurological disorders. In mania there is the raucous laughter that goes too far. Diseases affecting the frontal lobe of the brain can cause inappropriate laughter, where the brain has ceased to be able to distinguish between situations that can rightly be considered humorous and those that cannot. There is also a sort of epilepsy that manifests as nothing more than a mirthless laugh.

How easily we accept the different facets of laughter. Now all we have to do is take a few short steps: If we can collapse with laughter, is it not just as possible that the body can do even more extraordinary things when faced with even more extraordinary triggers?

Suzanne O'Sullivan is a neurologist in London and author of Is It All In Your Head? True Stories of Imaginary Illness

Border Crossings

Psychosomatic disorders testify to the power of the mind—and their very existence is a source of confusion.

The field of medicine increasingly recognizes that almost all disorders involve the mind as well as the body; as a result, the traditional mind-body distinction is gradually giving way to a more wholistic view of illness. Still, some disorders seem to especially straddle the mind-body border in ways that defy attempts to label and classify them neatly.

In DSM-5, the term "somatic symptom disorder" designates a mental disorder that causes physical symptoms similar to those observed in physical disease but for which there is no identifiable physical cause. The classification is controversial because, in addition to "conversion disorder," which involves actual loss of bodily function, as in paralysis and blindness, it includes:

- Illness anxiety disorder, involving persistent and excessive worry about developing a serious illness

- Pain disorder

- Body dysmorphic disorder, marked by excessive concern about and preoccupation with a perceived defect of physical appearance

- False pregnancy—which in the 1940s occurred in one of every 250 pregnancies in the U.S. but is now much rarer—is another manifestation of somatic symptom disorder.

Psychosomatic disorders may affect almost any part of the body, although they usually involve systems not under voluntary control.

Most people with somatic symptom disorder are seen in general medical settings.

Epidemiological studies estimate that 0.1 to 0.2 percent of the general population and 5 percent of those seen in general medical practice settings suffer from psychosomatic illness.

Facebook image: Dragana Gordic/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: Dmytro Zinkevych/Shutterstock