Protect Yourself from Emotional Contagion

Whether it’s joy or anger, we’re wired to catch and spread emotions. But with a little awareness, we can inoculate ourselves against too many negative ones.

By Carlin Flora published June 21, 2019 - last reviewed on January 14, 2020

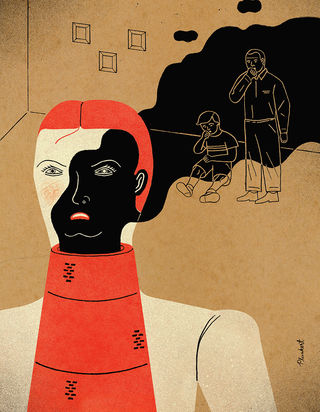

Growing up in 1970s Manhattan, in an apartment where such luminaries as Saul Bellow and Andy Warhol came over for raucous parties, Ariel Leve was often alone in her room at night. Yelling out for the grown-ups to be quiet and let her sleep, she lived at the whim of her narcissistic, volatile mother.

“I had no choice but to exist in the sea that she swam in. It was a fragile ecosystem where the temperature changed without warning. My natural shape was dissolved and I became shapeless.”

Leve’s story, recounted in her acclaimed memoir, An Abbreviated Life, is a heartbreaking portrait of how vulnerable we are, especially as children, to the force of others’ turmoil. She was subsumed by her mother’s feelings, desperate to anticipate the waves before they hit, and careful not to make them stronger when they did.

“When somebody’s mood can shift quickly,” says Leve, now 51, “you’re always on your toes and you’re always on guard, which means you can never really relax. And as a consequence, as an adult, I find that I absorb the mood and energy of other people very intensely, so I need a lot of time alone to decompress.”

Because of her emotionally volatile upbringing, Leve is all too aware of the effects of the emotions of others, especially since writing about her lifelong struggle to put her own equilibrium before that of others. But we are all constantly (and beyond our awareness) catching and giving each other feelings—joy and excitement, yes, but also emotions that are a detriment to our well-being. We live in an age where negative emotions can spread to hundreds online in the time that one unhappy family member dampens the spirits of a household.

Emotional Epidemiology

Elaine Hatfield, a co-author of a pioneering academic book Emotional Contagion and a professor of psychology at the University of Hawaii, defines “primitive” emotional contagion as the “tendency to automatically mimic and synchronize facial expressions, vocalizations, postures, and movements with those of another person and, consequently, to converge emotionally.”

The phenomenon happens, she argues, in three stages: mimicry, feedback, and contagion. Primitive emotional contagion is a basic building block of human interaction. It helps us coordinate and synchronize with others, empathize with them, and read their minds—all critical survival skills.

A review paper Hatfield co-authored in 2014 concluded that many studies had shown that people frequently catch one another’s emotions. Intense negative emotions that are expressed more emphatically are more contagious.

There is also considerable evidence that people feel emotions that are consistent with the facial, vocal, and postural expressions they adopt from others. When we mimic, the body gets feedback about the expressions we’ve taken on; we then feel what the other person is feeling.

There are factors that heighten susceptibility to emotional contagion, Hatfield says. These include seeing a connection between oneself and another person, being especially good at reading nonverbal behavior, engaging in frequent mimicry during the interaction, being a good judge of one’s own internal states, and being reactive to one’s own emotional experiences.

And sometimes, instead of matching another’s anger, we get scared, just as Leve responded to her mother. Hatfield calls this “counter-contagion” and theorizes in her review paper that anger is indeed “caught” in these cases, but it is quickly swamped by fear, out of self-protection.

Repeatedly catching negative emotions from the people in our lives can create a miasma—preventing us from seeing the contagion or its cause. Instead, we sense we’re in an unhealthy environment. And in worst-case scenarios, emotional contagion leads to harmful actions.

Gary Slutkin, a physician, epidemiologist, and founder and CEO of the nonprofit Cure Violence, sees emotional contagion—anger that erupts into violence, in particular—through the lens of public health. He says that this kind of emotional and behavioral contagion spreads in communities, not unlike a virus, through four mechanisms that involve the brain: The first engages the cortical pathways for copying, a behavior related to mimicry. “You’re safer when you’re doing what others are doing,” Slutkin explains. “For humans, it amounts to being part of a group instead of being left out on the savanna on your own.”

Copying is one way we learn: The language of the group, after all, is “contagious” to developing babies. The behaviors that are most contagious are those that are the most emotionally engaging as well as the ones carried out by the people who are most relevant to you. Salience is key when it comes to the copying response.

The second mechanism of emotional contagion is the brain’s dopamine system, which works in anticipation of a reward. “Activation of that system puts you down a pathway toward what is important socially and for survival,” he says. If you anticipate that you will be rewarded for responding to someone with anger or violence, you are more likely to get on that behavioral track.

If you veer off or are shut out from getting a reward, Slutkin says, the brain’s pain centers are activated. “A sense of I can’t stand it lights up in the context of disapproval.” That’s the third part of this intricate biological system that keeps you on a path of emulating peers. In the case of the inner-city violence (and even school and other mass shootings) that Slutkin works to reduce, the path might be paved by a group that is thought to expect you to shoot someone who insults or betrays you and rewards you for doing so. If you don’t, you’ll be excluded.

The fourth mechanism is trauma. For people who have experienced serious injuries or abuse, the limbic system and amygdala in the lower brain become hyperreactive. “This causes you to be less in control, which accelerates violent behavior,” Slutkin says. It also makes you more likely to get angry and be quick to react. “Then there’s hostile attribution, another part of what happens with the limbic system by which even small things are perceived as large affronts.” Misunderstandings metastasize until someone gets shot.

Infections Online and IRL

Much recent research on emotional contagion looks at how it plays out on social media. A 2018 study from Tilburg University in the Netherlands found that viewers readily catch the emotions of popular YouTube vloggers. When viewers see a positive post, they react with heightened positive emotions, and the same pattern holds true for negative posts.

Though they were later criticized for their invasive methods, a team led by Adam Kramer, a Facebook data scientist, tested emotional contagion by manipulating the newsfeeds of more than 680,000 users of the platform. Some were given more positive posts and fewer negative ones, and others were given the opposite social media diet. After analyzing more than 3 million posts, the team found that people exposed to fewer positive words made fewer positive posts themselves, whereas those exposed to fewer negative words made fewer negative posts. You feel your feed.

Amit Goldenberg, a graduate student in the department of psychology at Stanford University, looked at online social justice movements and found an “amplification effect,” wherein people like replies that are more emotional than the original tweets.

“I’m trying to understand what type of psychological mechanisms lead some things to be more contagious than others,” Goldenberg says. “Take, for example, the Black Lives Matter movement. People who are active online in these domains not only have certain emotional responses, but they’ll also have certain motivations. They want to express stronger emotions because they believe that such emotions may convince others to join, or because they want to use their emotions to exemplify their true group membership.”

Goldenberg believes that these emotional motivations build up over time, as after repeated cases of police brutality against black people. “So as people get exposed to more and more of these events, they are motivated to express stronger emotions, which increases their propensity for contagion.”

It’s an effect that happens in face-to-face interactions as well. “Imagine your kid misbehaves, and your partner underreacts,” Goldenberg says. “People tend to compensate for their partner’s lack of emotional response by amplifying their own.”

Social media responses are easier for researchers to measure than messy real-life dynamics. Real-life contagion is stronger than online contagion because it exposes us to more modes of emotional expression, such as voices, faces, and body language. There are just more channels for mimicry. One dramatic change in the last 10 years, however, is online exposure to greater levels of angry expression in response to any given situation.

Thousands of online entities screaming at once could, the logic goes, lead us to absorb more negative emotions than one yeller in front of us ever would. But even quiet people in our midst can shape our emotions and motivations. Social psychologist Ron Friedman at the University of Rochester has found that just putting people in the same room as a “highly motivated individual” improves their motivation and performance.

Conversely, when participants were paired with a less motivated person, they experienced a drop in their own motivation and performance. He notes, “Participants performed worse when they were seated next to an unmotivated office mate, even when they avoided verbal communication and worked on totally different tasks.” The effect was detected after just five minutes of exposure.

How could being physically near someone change our feelings, motivations, and behaviors? “Humans are social animals. We are constantly regulating each other’s nervous systems,” says Lisa Feldman Barrett, University Distinguished Professor of Psychology at Northeastern University. “I can text someone halfway around the world. They don’t have to see my face or hear my voice, and I can affect their breathing, their heart rate, and the amount that they sweat. I can affect the functioning of their entire nervous system and immune systems, for better or for worse, with a few words.”

In her research, Barrett makes a scientific distinction between affect and emotion. “Affect refers to simple feelings of pleasantness and unpleasantness, feeling worked up or feeling calm, that derive from the inner workings of your body,” she says. “Your brain is always regulating your body, and so you always have affective feelings, whether you are emotional or not.”

“Emotion is a specific way that your brain makes sense of what caused the sensory changes in your body that you experience as affect. Your brain uses past experiences of emotion to figure out what sensations mean and what you should do about them,” she adds. “A specific bodily change like a racing heart is not inherently emotional. It becomes part of an emotion when your brain links it to the surrounding situation, as your brain makes its best guess about how to act to keep you alive and well. This meaning-making is also something that humans can communicate and pass on to one another.”

Save Yourself and Protect Others, Too

Gary Slutkin’s antiviolence program is a roadmap for interrupting contagion. (Policing practices, he says, frequently accelerate it.) “We know how to reverse contagion,” he says. “It’s done by using very credible, accessible, trusted peers who are trained to cool people down; this deals with the traumatic part of it and buys some time.” Most people, after all, are not aware of emotional contagion and how susceptible they are to it in the first place.

The peer counselor then allows those who are susceptible to “catching” violence-inducing anger to feel that they will be okay and accepted even if they don’t act. That’s why the peer must be someone they respect. “Then, if you have a critical mass of people saying, ‘You’re fine to not do it,’ the individuals at risk get into a meta-state that allows them to step off that path and onto a different one.”

Raymond Chip Tafrate, the author of Anger Management for Everyone: Ten Proven Strategies to Help You Control Anger and Live a Happier Life, is a clinical psychologist and professor in the criminology department at Central Connecticut State University who also works with people at risk of lashing out after catching negative emotions.

Tafrate, however, stresses that people might be “catching” something that is not there to begin with. “We are wired to pick up on threats in the environment, which makes us susceptible to interpreting situations negatively.” We also create our realities with our beliefs, he says. If we go into an ambiguous interaction believing the worst of someone, we tend to act in a way that makes the other person more defensive or even antagonistic, confirming our original view.

Tafrate tells people to approach situations with a “plus-two mindset.” On a scale where negative 10 means a person is definitely a threat and positive 10 means the person is definitely a friend and ally, add two points to the initial assessment to set the stage for a better interaction. “Emotional contagion is an autopilot phenomenon. We encourage people to get off of autopilot and learn some skills.”

Choosing your company is one way to protect yourself from catching negative feelings. “Ask yourself,” says Tafrate, “‘With whom do I feel good? Who reinforces my strengths and best qualities? With whom am I the best version of myself?’”

It’s not that you should keep only perennially sunny friends. “The ideal person is not someone who is ‘positive’ as much as someone who is level-headed and willing to engage with you, including with your darker thoughts,” says Neel Burton, a psychiatrist who teaches in Oxford, England.

As for the people we are more or less stuck with, Burton points out that we have the power to cheer them up. “One of the best ways of avoiding contagion with people who are down is actually to engage with them. Talk through things, take a walk, and generally be supportive. Do things with them that will lift both their mood and yours,” he says.

When a person is upset around her, Barrett sometimes applies the trick parents use on their newborns—synchronizing breathing with an upset baby. “I have one friend who is pretty easily worked up,” she says. “Being around her can be stressful because our nervous systems might coordinate. Asking her to calm down is not so helpful. What I do instead is match my breathing to hers, and then I slow my own breathing down. Then her breathing slows, and she calms down.”

Barrett agrees that we need to take more responsibility for our emotions. Rather than make assumptions, we might try to “be more curious and less certain about what other people are feeling.” Your brain, she says, runs a metaphorical “budget” for your body, and we’re all more susceptible to catching bad moods if we’re running a deficit. “Eating well, getting enough sleep, and exercising are simple ways to inoculate yourself against affective contagion.” And online interactions, with their ambiguity, can be particularly taxing on the body’s budget, she warns.

“Never take anything personally” on social media, Burton adds. “People have their issues and they have nothing to do with you. Do not encourage or even engage with bad behavior online, or anything that doesn’t ‘feel right.’ Bad behavior breeds bad behavior: If you send out calm, positive signals, you are less likely to attract negative people.”

Hatfield takes lessons from insightful novels that inspire her to decode people rather than passively adopt their moods. “I’m reading Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, and he is a master at providing a sympathetic understanding of why obnoxious people act as they do. This doesn’t mean approving of a monster or letting yourself get pushed around. It’s simply that understanding helps us.” A cool, analytical distance shields us from emotional contagion, she adds. “There is research showing that if people have to view a horrific film, they feel less if they view it from an intellectual, anthropological perspective than if they just respond emotionally.”

Changing the behavior of an adult who thrives on negativity is unlikely, says Hatfield, and that attempt—again and again—can wear you out. If you’re dealing with an angry boss or anxious father, take time for yourself, especially if you’re a sensitive person who is “wonderful at understanding and dealing with others, but needs to recover.”

Ending contact with her mother (whom she could not change, after all) did provide some relief to Ariel Leve. She still struggles with managing her anxiety, but since she wrote her memoir, some underlying beliefs she had about herself have shifted. She used to think that love wouldn’t be sustainable and that she couldn’t have the life she wanted. Now, she has more faith in the future.

In raising stepdaughters, Leve has found a balance between “being herself,” or expressing emotions she couldn’t express when she herself was a child, and regulating or downplaying her reactions for the sake of the children.

“Growing up, I couldn’t have peace unless my mother was at peace,” she says. “So, her peace was paramount. And I have recognized that, as an adult, my peace is paramount. I’m not looking to others to set the tone for how I will feel now. I lovingly disconnect and allow others to have their moods.”

Leve grew up in a Manhattan penthouse and went to an exclusive private school, facts her mother dangled over her head when she felt her daughter wasn’t grateful for all she had. But of course, what young Ariel wanted was an emotionally stable environment. In one passage in her book, she writes: “I had friends whose families lived in walk-ups on narrow streets in darkened neighborhoods and whose bedroom windows faced brick walls. When I visited them, what I envied was a chance to spend time in a home without feeling on edge. Serenity was affluence. Consistency was opulence.” That absence of negative emotion—peace—was precious.

On the other end of the spectrum, there is lunch with a friend whose smile erases your terrible morning, or, better yet, mass positive contagion: the warm happiness that spreads through the room after a touching wedding speech, a funny scene made 10 times more hilarious by the raucous crowd in a movie theater, the explosion of pride in a stadium when an underdog triumphs. In those rare moments, when we amplify each other’s good emotions, it feels great to be human.

Control Yourself!

How not to contaminate others with your bad mood.

Realizing your power to color a room via contagion—especially in your own home—can be a strong incentive to keep emotions in check. Here are some tips for safeguarding colleagues, neighbors, and loved ones from your moodiness.

Inoculate yourself first: Make yourself less susceptible to bad moods that you can easily pass on to others. This includes the basics—get adequate sleep, eat well, exercise, and cultivate a sense of purpose.

Cope by compartmentalizing: You might think you have every right to be cranky, but if you consider how it imposes on others’ right to hum along in a content state, you might set aside your negative thoughts and emotions. Consider putting your bad mood up on a shelf when it’s time to interact with people. (You can always wallow later.)

Ask for feedback: Within long-term relationships, show self-awareness by asking your partner whether you’re too often setting a bleak tone. If so, work to regulate your sadness, anger, and anxiety with therapy, mindfulness, cognitive reframing (looking at a situation from different perspectives), or by modifying your expectations.

Incite positive contagion: James Fowler, a professor at the University of California, San Diego who has extensively studied social networks and how moods like happiness spread through them, says he started playing upbeat pop songs on his way home from work so he could greet his two sons in a giddy state. Think of ways to proactively boost your loved ones’ moods.

Quarantine yourself: If you’re really irritable, consider hiding away, says psychiatrist Neel Burton. “You might avoid going to that dinner party and just go to bed early instead.”

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the the rest of the latest issue.

Carlin Flora, a former PT features editor, is the author of Friendfluence: The Surprising Ways Friends Make Us Who We Are.