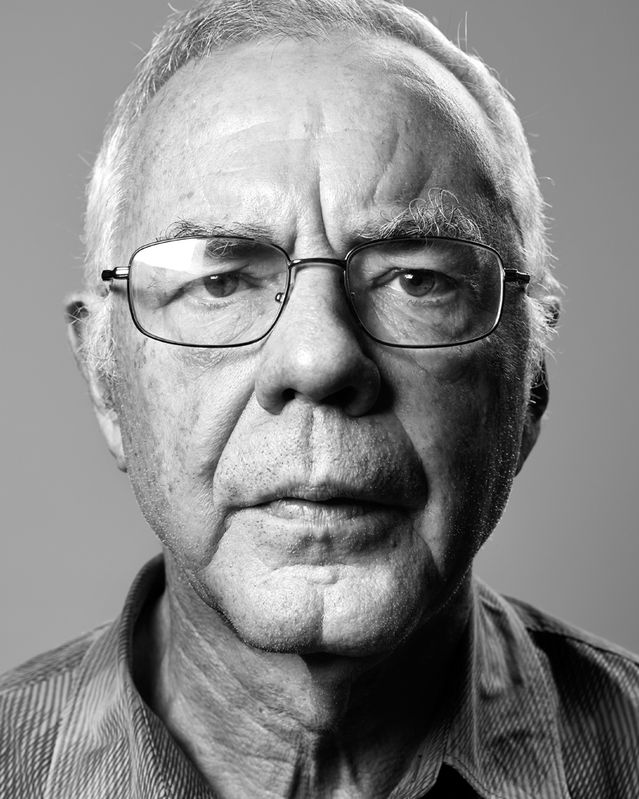

Trivers' Pursuit

Renegade scientist Robert Trivers is lauded as one of our greatest thinkers—despite irking academia with blunt talk and bad manners.

By Matthew Hutson published January 5, 2016 - last reviewed on June 26, 2020

To call Robert Trivers an acclaimed biologist is an understatement akin to calling the late Richard Feynman a popular professor of physics. As a young man in the 1970s, Trivers gave biology a jolt, hatching idea after idea that illuminated how evolution shaped the behavior of all species, including fidelity, romantic bonds, and willingness to cooperate among humans. Today, at 72, he continues to spawn ideas. And if awards were given for such things, he certainly would be on the short list for America’s most colorful academic.

He was a member of the Black Panthers and collaborated with the group’s founder. He was arrested for assault after breaking up a domestic dispute. He faced machete-wielding burglers who broke into his home and stabbed one in the neck. He was imprisoned for 10 days over a contested hotel charge. And two men once held guns to his head in a Caribbean club that doubled as a brothel.

Fisticuffs aside, what propelled Trivers into the academic limelight were five papers he wrote as a young academic at Harvard—including research on altruism, sex differences, and parent-offspring conflict. This work won him the 2007 Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Crafoord Prize in Biosciences, the Nobel for evolutionary theory. The award came with half a million dollars and a ceremony attended by the queen.

Steven Pinker has called him “one of the great thinkers in the history of Western thought.” Yet Trivers has not led the life of your typical contemplative academic. Mental breakdowns, public feuds, and near-death experiences have peppered his career, distracting him from his work even as they’ve nourished it.

No one is quite sure what to make of him, but all agree he is both brilliant and volatile, a sort of Steve Jobs without the colossal second coming. In a new memoir, Wild Life, he contrasts his existence with the “often solitary and intensely internal” one he sees in most scientists. “[That] kind of life,” he writes, “never appealed to me.”

To begin, Trivers’ revolutionary 1970s papers presented no new data. Trivers simply offered entirely novel ways of looking at what was already there, along with new avenues for moving science forward. His dissertation was so strong that when he showed up before the evaluating committee, which included such luminaries as E. O. Wilson and Ernst Mayr, they skipped the charade of making him defend it and simply offered their congratulations. Yet he published little follow-up work. A scientist can build a whole career milking a single small concept, but Trivers has been known to put forth a big new idea and then essentially drop the mic.

Trivers’ first paper, on the evolution of reciprocal altruism, described a theoretical model showing how altruism among strangers could naturally develop—people cooperate with the expectation of similar treatment from others. This model explained a wide variety of feelings and behaviors, from friendship to moralistic aggression. The emotion of gratitude, for instance, evolved to motivate us to return favors, encouraging cooperation. Guilt motivates us to repair relationships we’ve harmed. Anger makes us avoid or punish those who have harmed us. And gossip makes us mindful of our reputations. Trivers suggested that complex strategies of cheating, detecting cheating, and the false accusation of cheating (itself a form of cheating) pushed the development of intelligence and helped increase the size of the human brain.

Next, in Trivers’ second paper, he hypothesized that a single factor drives sex differences across all species. He argued that differences in parental investment—the energy and resources invested in an offspring—lead the sex that invests more (females, in most species) to focus on mate quality and the sex that invests less (males) to seek quantity. So in humans we expect choosiness in females and aggression between males as they vie for females. The theory has tremendous explanatory power, from justifying the brightly colored feathers of male birds to illuminating why sexual jealousy is a leading (and, until recently, legally defensible) cause of homicide—men prize their mate’s fidelity above all.

In another paper, Trivers conceptualized offspring not as passive recipients of parental investment, but as independent actors, generating the theory of parent-offspring conflict. A child wants disproportionate attention and resources for him- or herself, but a parent wants to spread the goods equally between all offspring. And so we have kids who bawl until they get what they want, siblings who maintain lifelong rivalries, and parents who try to instill equality no matter how selfish the kids’ tendencies. It was for these three papers, plus another two, on insect colonies and on parents’ ability to vary the sex ratio of their offspring, that he won the Crafoord.

In each paper, he found a simple, clear idea, and took it as far as it would go, wrapping diverse and widespread phenomena together in one neat package. You might not have made the connections before, but once you see them, they’re quite clear. “Trivers has answered some of the most profound questions about the human condition,” Pinker told me. “Namely, why are our relationships with other people such complicated mixtures of cooperation and conflict? He did so with a simple, though nonobvious, analysis of the patterns of overlap and nonoverlap of our long-term genetic interests.” According to David Haig, a geneticist at Harvard and a longtime friend and collaborator of Trivers, “Bob has a great ability to see questions as simple and not be distracted by details.” Richard Dawkins praises him for applying economic ideas to biology “with greater clarity of mind than any biologist since R. A. Fisher,” the knighted geneticist.

In their own books, E. O. Wilson and Richard Dawkins drew heavily on Trivers’ papers, although he has not always had positive things to say about his popularizers. “Richard wrote a beautiful book,” Trivers says about The Selfish Gene. “I was not about to take the time to do it.” But as for Wilson and Sociobiology, “He played the old Harvard game of becoming the father of a field by becoming the father of the name of a field.” (Wilson told me his own work on the sociobiology of insects actually influenced Trivers.)

After writing papers addressing how we treat strangers, friends, lovers, parents, and children, Trivers offered a no-less-powerful theory on how we deal with ourselves. In a sentence in the foreword to Dawkins’ book, he proposed that self-deception evolved to facilitate the deception of others. Trivers says he’d planned to flesh out the theory but didn’t get around to it because he was “smoking too much strong herb.”

Trivers also made a mark with the 2006 textbook Genes in Conflict, for which he and Austin Burt spent 15 years integrating thousands of papers on genetic competition within organisms. A reviewer for Nature Genetics called it “meticulously assembled, thought-provoking, and sometimes deliciously speculative.” According to Trivers, “We created an entire field, the evolutionary dynamics of within-individual genetic conflict. So first, I worked on social theory between individuals, then I dropped one level lower.” Proudly showing me its color inserts, he pointed to what appeared to be a drumstick. “Looks like a piece of chicken, right? No, it’s the only transmissible cancer known. That’s a dog dick. He punches it into a female, the cancerous tissue breaks off and starts growing inside her pum pum.”

My early emails with Trivers attested to his mercurial nature. He lavished praise for a hypothesis I’d suggested, then scolded me for failing to answer a question he’d written. After some back and forth, he agreed to an interview and last spring met me at the train station in New Brunswick—he’s currently a professor at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. Wearing a wool hat with a weed leaf on it, he grumbled at my not finding the right station exit. He warmed up as we drove to his disorganized apartment—a mattress remained in the middle of the floor from a visit by his son. One wall displayed photos of his family, a former girlfriend and her family, and a lizard. We cracked open beers, and he soon offered me a puff of his joint as we got down to business.

The son of a diplomat, Trivers grew up in Maryland, Denmark, and Germany. At age 12, he knew he wanted to be a scientist and took a liking to astronomy, then to math. He spent two months mastering a calculus textbook and another two months mastering the next volume. He studied pure math as a Harvard freshman, but as a sophomore he realized it wasn’t likely to yield many applications, so he briefly looked to physical science. He didn’t have a knack for physics, however, and hadn’t learned much chemistry or biology. (His college roommates once showed him pictures of a hippo and a rhino and asked him to identify which was which. He picked wrong.) “So, I literally said, ‘Well, if it’s not truth I’m going to devote myself to, then it’s justice.’” He identified with the civil rights movement and decided to become a lawyer. Unfortunately that meant plodding through a major in U.S. history, which he found to be “an exercise in self-deception and self-glorification.”

During his junior year at Harvard, Trivers had a mental breakdown. After five weeks of mania—little of which he remembers besides insomnia and feelings of grandiosity—he checked himself into the hospital and stayed for 11 weeks. Doctors diagnosed him with bipolar disorder. When he returned to school, he thought it might be a good idea to take courses in psychology—though not abnormal psych because, as he likes to say, “I had a special advantage in it.” But he soon decided psychology in its then state was not a real science.

The field at the time had three strands: First was work on conditioning, pioneered by Ivan Pavlov and B. F. Skinner. Skinner “was stupid enough to think you could build up a whole theory and system of logic about human psychology based entirely on learning,” Trivers says, “and specifically the kind of stimulus-response learning that’s studied in the lab.” Trivers didn’t see how, for example, the brain could pick up the complexities of language this way without some genetic scaffolding. Then there’s Freud, who had some keen insights into self-deception, Trivers says, “but he wedded them to a completely corrupt view of human development” characterized by the anal, oral, and Oedipal stages. “He just invents it out of whole cloth while snorting too much cocaine.” Third was social psychology, which Trivers saw as too dependent on self-reports. “You cannot build up a science based on a whole series of correlations between how people answer questionnaires,” he says. “By definition it can’t work, if only because we don’t know most of what’s causing us to do things, and second, we don’t necessarily tell the truth.” Trivers considered psychology “a joke.”

So he stuck to justice and applied to law school. He selected the progressive law school at Yale, with Virginia as a backup, but neither accepted him, in part because of his mental health. “But for his mental illness,” says William von Hippel, a friend and collaborator at the University of Queensland, “he would not be the famous scientist that he is. He’d be a well-to-do lawyer.”

Suddenly without a clear path, Trivers heard about a job writing children’s books. He took his writing sample, an account of his breakdown, to Jerome Bruner, the Harvard psychologist running the project. “I was hired. Strange, eh?” He was assigned to write about biology, a topic he knew nothing about (hippo or rhino) and to work under the wing of the naturalist and bird expert William Drury. Together they would sit in the woods imitating bird sounds so they could watch avian courting, clashes, and cooperation. Under Drury’s tutelage, Trivers decided to become an evolutionary biologist. Upon discovering evolutionary logic, he says. “I knew I had found where I wanted to be.” He has called Drury “the man who taught me how to think.”

Trivers headed back to Harvard to earn a Ph.D. in biology, studying under Ernest Williams, a herpetologist. Trivers decided to study lizards in Jamaica and became enamored with the island—not least because he finds dark-skinned women attractive and says that at that time a white man couldn’t roam Boston with a black woman on his arm. “So I always felt free down there in a way that I never felt here,” he says. He has lived in Jamaica on and off since 1968 and frequently falls into Jamaican patois, speckling his speech with its slang (pum pum, raas huol).

He has many tales to tell of Jamaica. One is a memorable stickup in an East Kingston club. That story begins when he visited the establishment after a hiatus, curious to see if things had gotten as bad as he’d heard. When he entered, two men put guns to his head as three more gunmen stood by. They pulled the money from his pocket and pushed him against a wall next to a man bleeding from the head. When the next victim arrived, Trivers dashed out the door. After reporting the robbery to police, he learned that they and the community had sanctioned the ambush as a form of extrajudicial punishment for the johns. But as a white man, whose death would have caused major scrutiny for the area, he was a surprise inconvenience. The robbers had let him flee. According to Trivers, one woman who saw him running down the road later said to him, “Massah, me nebber know white man could fly, until I see you go by.”

Trivers also nurtured a family in Jamaica. He has two Jamaican ex-wives, five children, and eight grandchildren. One daughter is now the principal of a charter school in Harlem.

After finishing his Ph.D. in 1972, Trivers joined Harvard’s faculty. In 1977, he sought tenure, but the decision was pushed back three years because of his mental health issues. Instead of waiting, he decamped to the University of California at Santa Cruz with his wife and son in tow.

In Santa Cruz, Trivers met Huey Newton, then a Ph.D. student and the leader of the Black Panthers. They became close, and in 1979 Trivers joined the party—for which he says he’s done “an illegal thing or two.” Trivers still refers to himself as “my black ass,” which he picked up from Newton, who told him: “Bob, everyone’s ass is black if you look closely enough.” Together they wrote an article for the magazine Science Digest about self-deception in the pilots of Air Florida Flight 90, which had crashed into the Potomac River upon takeoff in 1982, killing 78. A friend of Trivers, the Harvard butterfly expert Bob Silberglied, had died in the crash. Trivers was also drawn to the cockpit conversation replayed on TV. “You could hear the fear and rationality of the copilot,” he says, “and the overconfidence of the pilot, who showed fear only when they were in the air and it was too late.”

In their article, they analyze the NTSB transcript line by line. The copilot repeatedly expresses concern about snow accumulating on the wings, the need for more de-icing, and what he believes are faulty instrument readings. The pilot brushes him off. Finally, 49 minutes after their last de-icing, they take off. Without sufficient velocity, they pull up, and a few seconds later they stall. The plane grazes a bridge and plunges into the Potomac. “We imagine that presenting a falsely positive front may often have been advantageous to the pilot prior to Flight 90,” Trivers and Newton wrote, “giving him the illusion that skill plus overconfidence works in all encounters.”

The two began writing a book titled Deceit and Self-Deception, but the publishing house closed. Newton, Trivers recalls, “was a master at propagating deception, he was a master at seeing through other people’s deception, he was a master at beating people’s self-deception out of them, and like all the rest of us, he fell down when it came to his own self-deception.” In an interview with The Black Panther newspaper, he called Newton a “heavyweight mind,” in comparison to the many “light- and middleweight minds” he found at Harvard.

Trivers’ most detailed exploration of self-deception didn’t come until his 2011 book The Folly of Fools, where he explains that we fool ourselves in all realms of life—when overestimating our looks or abilities, when justifying our righteousness, when defending our power or privilege, when constructing false historical narratives. It’s all part of advancing our own agendas.

“What I’ve done is found disciplines,” Trivers says. As to self-deception, “I lost a lot by being sooo slow to develop suuch an important idea. Had I written the paper in ’78 like I was supposed to, there would have been a whole science now.”

In 1994, he moved to Rutgers to be closer to his children. There, he has continued to publish on evolution and human behavior. One area of interest has been body symmetry in Jamaican children as a measure of genetic ability to withstand stressors during development. In 2005, he co-authored a paper showing that more symmetrical Jamaican teenagers were rated better dancers. The study was featured on the cover of the prestigious journal Nature.

Later, however, another researcher had trouble replicating the findings, and Trivers took a closer look at the data. He found irregularities and concluded that William Brown, a postdoc and the paper’s lead author, had fabricated data. Trivers sought retraction from the journal, but Brown and Lee Cronk, a fellow Rutgers professor who had worked on the paper, denied any wrongdoing or mistakes. (Von Hippel said Cronk’s position is a classic case of self-deception, because a Nature paper was more important to his résumé than it was to Trivers’.) Trivers self-published a book, The Anatomy of a Fraud, to back up his case. Rutgers conducted its own investigation and came to the same conclusions as Trivers. In 2012, he stood in Cronk’s office and called him a “punk” for continuing to deny the allegations. Cronk claims to have felt threatened, and Trivers was banned from campus for five months. (Cronk declined to comment for this article.) Nature finally retracted the paper in 2013, five years after the initial request. “For me to produce a fraudulent result, know about it, and not do everything to expose it and prove it is anathema to the essence of my identity,” Trivers says.

Trivers’ latest dustup with Rutgers began at the end of 2013, when he was assigned to teach a course on human aggression and he protested that he didn’t know the material. After much back and forth, he showed up in class and told his students the backstory. The university suspended him with pay for bringing students into the dispute, then withheld his pay for three months. “I am one of the most accomplished scientists they have ever had, period,” Trivers says in a characteristic but not inaccurate self-assessment. “Why not treat him well?” he asks. He has taken a dim view of the university and looks forward to a conscious uncoupling. “Honesty is not their strong suit,” he says. “Remember, we’re talking about New Jersey.”

Trivers also had a talk at Harvard canceled once when he made a perceived threat against Alan Dershowitz in The Wall Street Journal letters pages over their conflicting views on Israeli-Lebanese relations. He admits to writing many “strongly worded” letters to people. And he notes: “If I ask you a direct question and you don’t give me a direct answer, I will wheel on you and say, ‘Yes but what about the question I asked you?!’”

When I asked Trivers how much blame he should take for the drama that surrounds him, he says, “I know I’m a hard man.” But he doesn’t see himself as violent. When he was kicked off campus for calling Cronk a punk, Rutgers sent him to a psychologist for threat evaluation. “After an hour and a half, the psychologist says to me: ‘You know something, Dr. Trivers? You’re not a danger to anyone, including any of your colleagues. Your problem is you call stupid people stupid, and if they have power over you, you get blowback.’” Trivers told me this not a minute after framing an off-the-record comment with: “Please, I will get violent if I see this in print, and I’m not joking.”

But this hard man is trying to change. He relies on strategies he developed years ago for managing his emotions, including something resembling prayer. He put religion aside at around age 13, “because math was a hell of a lot more interesting than ‘begat begat begat.’ And there was this little contradiction between religion and 13-year-old girls.” Now, he wishes he hadn’t neglected it so much. He doesn’t believe in a god who listens: “How does God have any time left for my moaning and groaning? It’s insane.” Instead, it’s more a meditation. “I pray to keep my anger under control, to be more compassionate, for forgiveness, but I regard myself as talking to different parts of my own psyche.”

Trivers sees himself doing another five to ten years of research, but he describes his current contributions as more humble. He pumps out papers on lizards and knee symmetry in runners, which he admits, were “designed to fly me to Jamaica at someone else’s expense.”

Yet one recent idea emerging from his interest in self-deception appears to have real significance: Research shows that older adults are biased toward paying attention to and remembering the positive over the negative and that they don’t dwell in negative moods, a phenomenon called the aging positivity effect. There’s been no functional explanation, and it would seem that such a bias could be dangerous by blinding people to hazards. But Trivers notes that positive moods improve immune function, and older adults have a greater need for a strong immune system to fight off tumors and other ills. So maybe we’ve evolved to cheer ourselves up as we age just to boost immunity.

He suggested the idea to von Hippel, who didn’t buy it. Why would natural selection shape old age, after we can no longer reproduce? But, Trivers argued, you can still help raise your grandchildren, who carry your genes. Von Hippel ran a test that found that in older adults, a greater positivity bias correlated with stronger immune function. So they published the findings in 2014 in Psychology & Aging. Now they’re working on a longitudinal study to see if positivity predicts later immune function.

Trivers refrains from making grand predictions about the future of evolutionary theory, but he has certain interests. David Haig’s work on genetic conflict excites him, as does von Hippel’s work on aging. And he’s just applied for a yearlong fellowship at Harvard to study honor killings. “How in the world,” he wonders, “do you select for, if indeed you do, murdering your own daughter?” He also has a lifetime interest in homosexuality—another genetic conundrum—and plans to write a review paper. “I enjoy trying to think through those kinds of problems,” he says. “As a theoretician you’re attracted, or you ought to be, to precisely those phenomena that seem to contradict your theory, and the deeper the better.”

Eating dinner at a Thai restaurant with Trivers, I mentioned that a colleague of his had painted him to be something of a badass. As evidence I noted the time he stabbed the home invader in the neck. “That’s a badass?” he inquired between slurps of soup. “That ain’t a badass. That’s someone protecting his f*cking life. I came an inch from being killed, man.”

Fair enough. But hurting his case, he went on to describe his response to the criminals’ lenient sentences. “I chased down both of them, because I had to,” he says. “Since the police aren’t disciplining them, I will.” One morning he spotted one of the men and pulled his car over. “‘Listen,’ I say, ‘If you want to rob me, you rob me at the roadside. Don’t rob me in my own home. That’s where my children live, that’s where my guests are. I will kill you three times over. In fact...’” As he started to get out of his car, Trivers says the man ran backward. (Helpfully, Trivers boxed in boarding school at Andover; but still, during one separate altercation, he ended up with an ice pick to his hand.)

Today, Trivers retains vitriol for those who don’t see the legitimacy in his work and the research it’s spawned. According to von Hippel, people reject evolutionary psychology for ideological reasons. Those on the right fear that it absolves us of responsibility, while those on the left fear that accepting inherited differences hinders the goal of social equality. Trivers says that many feminists and cultural anthropologists regard him as “the devil.” In return, he calls them “feebleminded” and “stone nuts.” More genes are expressed in the brain than in any other tissue, he notes, and to ignore the partnering of nurture with nature is “ludicrous, if you have any serious interest in reality or science.”

Trivers feels grateful for everything evolutionary biology has given him. It’s taken him around the world to wild and often unwelcoming places, and it’s given him the tools to analyze what he’s seen, from lizards to lovers’ quarrels to leftist movements. “In short,” Trivers writes in his memoir, “I signed on to a system of thought that allowed me to study life and live it, sometimes very intensively.”

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. For more stories like this one, subscribe to Psychology Today, where this piece originally appeared.