Habit Formation

Your Habits Aren't Bad. They're Just Outdated.

Habits have a half-life. To live well, they must be upgraded or replaced.

Posted May 23, 2023 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Habits are a kind of biological software that one executes to solve problems and complete tasks.

- While everyone knows software programs need to be regularly updated, they fail to apply this logic to habits.

- Obsolete software causes problems and can't keep up with new needs. Obsolete habits have the same limitations.

The next time you turn on your smartphone, power up your PC, or log in to your tablet or laptop, reflect on the frequent ritual you go through to keep the device software updated.

Whether these updates occur weekly or even just once a month, two things are likely:

- The first is that whether it is an operating system like Windows or Safari, antivirus software, or a utility program such as Gmail and Microsoft Office, this update process never ends. The updates may vary in timing and content, but they otherwise just keep coming.

- The second likelihood is that periodic updating is necessary for the device to keep up with current needs and problems. Intuitively, we'd usually prefer to keep using the same old software and programs in their more familiar form. Yet we also appreciate that the hassle of updating software is critical to keeping them secure, correcting errors, and adding desirable new features. Like an Atari video game station or rotary telephone from the 1980s, outdated devices and software may still technically work. Yet they will be increasingly vulnerable to problems and unable to meet the demands of our current lives.

Now consider that habits are simply the equivalent of behavioral software. Just like computer software, our habits can become outdated and obsolete. However, the consequences of the latter can be far more dire.

Habits as behavioral software

How often do you consciously update your habits? Is it as often as your smartphone updates its software, or are you perhaps still operating with "habit-ware" written years ago, perhaps even as long ago as your childhood? If the latter, how well are habits programmed many years ago serving you in the present?

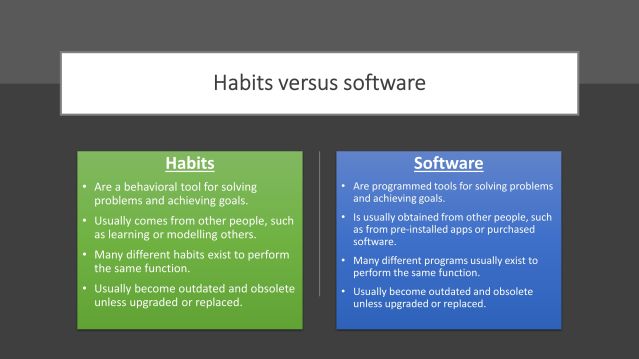

Treating habits like software (See Figure 1 below) is a far superior approach to living with outdated behavior programs. Taking the time to regularly update habits—adjusting them to match our current values, goals, and resources—is one of the most effective tactics people can employ to get out of Sisyphean life ruts, improve physical and mental health, and enjoy lives containing more meaning and growth.

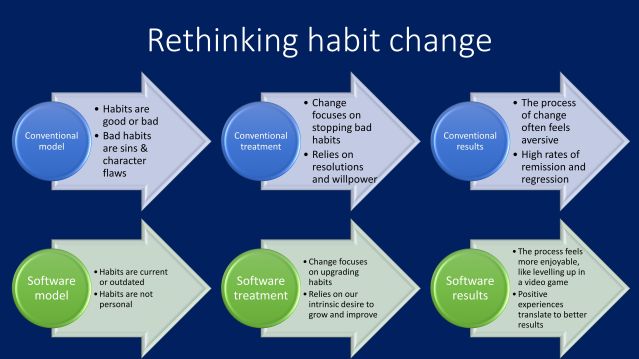

Compared to the conventional good-versus-bad way of thinking about habits, this "habits as behavioral software" analogy offers multiple liberating benefits (see Figure 2 below):

- Once we realize that our so-called "bad habits" are mostly just outdated habits, we can drop the negative emotional baggage. Even habits that are widely maligned—such as smoking cigarettes or abusing alcohol—probably served an original purpose. Smoking may have helped us fit into a peer group, manage stress, or manage weight, for instance. Similarly, a habit of excessive alcohol use may have arisen to cope with pressures during college or the military, after a traumatic experience, or as a way of self-medicating depression or loneliness. Neither the habit nor the person is "bad." Thinking so only makes the person feel worse and likely compounds the problem. Instead, consider that using nicotine or alcohol to address an important life problem is parallel to using a dial-up modem for internet access or riding a horse to get to work. These solutions may have been useful initially, perhaps even the best available option to us at the time. But they've become inferior options in the present and would benefit from an upgrade.

- Habit change becomes less about willpower and more about personal evolution. Most of us have probably experienced the struggle of trying to stop a "bad" habit. It demands self-discipline, resolutions, and the ability to resist temptation, repeated over many days and weeks. Yet how much of this adverse experience is in fact merely a creation of the negative cultural mindset we have about habit change? Does habit change have to be unpleasant? Habit science suggests no1-2. This science instead indicates that successful habit change often results from the process of replacing—not stopping—old behavior patterns with new and more functional alternatives. That is, just like software upgrades, we change habits by revising and improving the former behavior code with updated language to get better results with fewer downsides. This approach to habit changes means less reliance on willpower and more focus on learning. It reduces the burden of guilt and shame while enhancing the emphasis on personal improvement. Habit change is essentially a kind of accelerated personal evolution, where we seek to consciously optimize our behaviors to meet the challenges of our current environment. It can be a rewarding journey based on self-growth instead of an exercise in self-flagellation.

- It gets rid of the quick-fix mentality. Effective habit change isn't a one-time process of replacing outdated behaviors with new behaviors. This common but flawed perception only leads to the new behavior becoming equally outdated over time. Effective habit change, instead, is an ongoing practice of routinely evaluating our behaviors, goals, and circumstances, making adjustments to our habits to meet the moment. From this perspective, habit change is more like growing a garden or managing a business than running a marathon. There is no finish line to the process. It is, in the words of author and speaker Simon Sinek, an infinite game3. As soon as you stop playing the game of habit change, you also stop learning, growing, and developing the behavioral tools to live your best life. If your goal is a great life, the solution is to never stop upgrading your habits.

References

1. Wood W, Rünger D. Psychology of Habit. Annu Rev Psychol. 2016;67:289-314. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417.

2. Gardner B, Lally P, Wardle J. Making health habitual: the psychology of 'habit-formation' and general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 Dec;62(605):664-6. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X659466.

3. Sinek, S. (2020). The infinite game. Portfolio Penguin.