Alcoholism

A Suicide Prepared for a Long Time

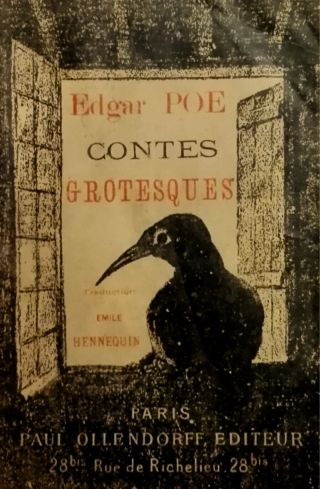

A glimpse into the troubled life of Edgar Allan Poe.

Updated August 14, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- In his mid-20s, Poe lost his first major literary job due to drinking, in a pattern to be repeated often.

- He viewed drinking as a way of fleeing "torturing memories" and "a dread of some strange impending doom."

- In 1847, he believed that the death of his wife was a "permanent cure," but he quickly returned to the bottle.

- In 1849, at age 40, he was found lying stuporous on a street in Baltimore and died in a delirious state.

At the end of the first portion of this two-part article, Poe was in his mid-20s, recently married to his 13-year-old cousin, and though initially acting responsibly, he ultimately resumed drinking. In a pattern to be repeated many times, he lost his first significant scholastic job as an editor at The Southern Literary Messenger. He moved from city to city, working briefly at various newspapers or journals before being let go, and freelanced his stories and poems. His intoxicated appearances in public settings led to notoriety, but his productivity continued, including two stories that may have been the first in the science fiction genre, as well as "The Murders in the Rue Morgue," likely the world’s first detective fiction, and in 1845 "The Raven."

His behavior became more erratic as time passed. On one notable day, he was drunk and failed to arrive for an appointment with President Tyler, who was prepared to discuss the possibility of steady work in the government. He often took to his bed with ill-defined disorders in a manner reminiscent of his contemporary Charles Darwin and sometimes feared that, like his wife, he may have contracted tuberculosis.

After Virginia died in 1847, Poe pursued several other women with great ardor, which remained chaste and usually resulted in new poems about them. At first, he thought he could control his drinking, writing, "I had, indeed, nearly abandoned all hope of a permanent cure when I found one in the death of my wife." His abstinence was short-lived. He often disappeared for days at a time, and the extreme degree of intoxication manifested in public led to rumors of drug use as well. He began to have trouble concentrating and suffered from headaches, which he described in his poetry.

After a particularly notable drinking bout in Philadelphia in 1849, he returned to Richmond. There he reconnected with Elmira Royster, the now-widowed sweetheart of his younger years. He wooed her, and she agreed to become engaged once again, with the stipulation that he stop drinking.

Though he made some efforts, it was not to be. He left for a trip to Baltimore en route to New York but went missing for six days before being found stuporous on the street outside a tavern, wearing someone else’s clothes (he likely sold his own for drinking money). In his final days in Baltimore’s Washington University Hospital, he was delirious, agitated, conversing with hallucinatory figures on the walls, and calling out for "Reynolds" (who has never been identified). He died on October 7, 1849, in what the poet Charles Baudelaire described as "almost a suicide, a suicide prepared for a long time" (1).

Poe’s Thoughts on His Drinking

Poe had been known for his heavy drinking going back to his college days. It had a driven, relentless quality and did not necessarily seem to give him pleasure. He wrote, "I have absolutely no pleasure in the stimulants in which I sometimes so madly indulge. It has not been in the pursuit of pleasure that I have periled life and reputation and reason. It has been the desperate attempt to escape from torturing memories."

Other Substances Besides Alcohol?

Poe’s favorite drinks were whiskey, brandy, and absinthe. His friends were struck by the wildness of his behavior while drinking. The psychiatrist Donald Goodwin (4) raised the interesting point that Poe’s excited, delirious states often occurred during his drinking rather than during withdrawal hours or days later, which would have been characteristic of delirium tremens. He argued that this may have resulted from Poe’s fondness for absinthe, which, unlike most typical alcohol drinks, additionally contains the herb wormwood that can potentially induce agitated delirium and hallucinations during intoxication. Whether the toxic effects of absinthe are related to its very high alcohol content, sometimes approaching twice that of whiskey, or to its herbal constituents remains unresolved.

Whether Poe was also addicted to opium is an ongoing matter of debate (4). On the one hand, his sister and cousin said that he was; on the other hand, two physicians who were well acquainted with him, as well as a number of friends, believed this was not the case. Opium certainly appears in many of his stories, though it has been argued that the effects he ascribes to it do not resemble opium intoxication or withdrawal symptoms.

In those years, laudanum (opium dissolved in alcohol) was a legal and easily available medicine for gastrointestinal disturbances, though, of course, often used recreationally. Goodwin also noted that Poe’s own delirium, agitation, and hallucinations were not typical for opium, which tends to produce "a state of profound passivity" (4). Alethea Hayter, who studied Poe in depth in Opium and the Romantic Imagination (5), believed that whether he was addicted to opium could not be determined. Other authors have speculated inconclusively that a contributor to his final decline may have been toxicity from mercury-laden medication he was given after exposure to cholera in the months before his death.

It is uncertain whether Poe’s description of drinking was a way of fleeing "torturing memories," as he asserted, or whether this represented a kind of romantic rationalization. He may have had a genetic predisposition to drinking insofar as his father and older brother abused alcohol. It’s clear that while intoxicated, he often appeared wild and delirious with hallucinations, which are hard to explain on the basis of alcohol alone. His drinking led to erratic behavior, which cost him his jobs time after time, later affected his concentration, and ultimately contributed to his death at age 40. As such, he is often seen as a romantic, tragic figure.

Alethea Hayter made the intriguing comment that "Everyone who writes about him chooses their own Poe" (5). Some have seen him as driven by a need to please a cold father figure, struggling to come to grips with the untimely deaths of his mother and wife, or being caught between the simultaneous attraction to and fear of women. Like Charles Darwin, he often appeared to be a mirror in which authors see reflections of their own interests or theories. One point on which most can agree, though, is whether by intent or not, he left a legacy of the image of the brilliant but troubled and alcoholic writer.

Portions of this article are adapted from Fragile Brilliance: The Troubled Lives of Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe, Emily Dickinson and Other Great Writers.

References

1. Cavendish, R.: The death of Edgar Allan Poe. History Today, Vol. 49, October 10, 1999.

2. Marsden, S.: Visions of Poe. Knopf, 1988.

3. Letter to George W. Eveleth, January 4, 1848; Delphi Classics, 2011.

4. Goodwin, D.W.: Alcohol and the writer. Andrews McMeel, New York, 1988.

5. Hayter, A.: Opium and the Romantic Imagination. Faber, 1968.