Psychiatry

Going Full Circle in Precision Psychiatry

Navigating the path of precision: Insights into modern psychiatry

Posted February 26, 2024 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Treatments in medicine have for a long time been directed by the diagnosis of the patient. With an increasing understanding of the heterogeneity frequently seen among patients with the same diagnosis, there is an increasing wish to subclassify patients within a diagnostic category, to be able to apply treatments that are directly aimed at the core of the biological disturbance to achieve superior efficacy in the subset of patients.

This insight has led us into the field of personalized medicine, or precision medicine, that is transforming medicine. Much of the work started in oncology, driven by the insight that some tumors are characterized by biological changes that are relatively easy to detect, and to which specific treatments can be developed.

A good example can be seen in the field of breast cancer. Approximately 15 percent to 20 percent of breast cancer tumors have increased levels of a protein known as HER2. The tumors can be analyzed using laboratory tests to determine if the cancer cells have a high level of the HER2 protein. Such tumors are referred to as HER2-positive. These cancers tend to grow and spread faster than HER2-negative breast cancers. However, they are much more likely to respond to treatment with drugs that target the HER2 protein. Several such drugs have been developed, based on monoclonal antibodies that bind to the HER2 protein, or kinase inhibitors that block the enzymatic activity of the HER2 protein. Thus, the intervention is specific to the biological disturbance.

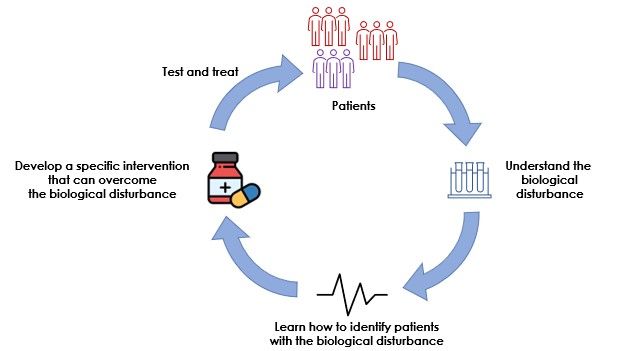

The oncology community has thereby been able to go full circle to make precision medicine a reality, by first characterizing the biological disturbance, then finding a way to detect it in patients, then developing a treatment, whereafter patients with breast cancer can be tested, and if found to be HER2-positive, receive a personalized treatment, which will improve the prognosis.

On the brink of transformation

The personalized medicine approach has for obvious reasons gained much interest in other areas of medicine, and the interest in precision psychiatry is blossoming. However, the challenge is different in psychiatry, where some of the more common disorders, with a relatively strong heritability, do not seem to be attributable to mutations in one or a few genes. Instead, much work is focused on understanding patterns in large datasets from patients. Sources for the information can be genetic, epigenetic, proteomic, etc., and even be based on physiological measurements of brain activity, heart rate variability, and potentially also on cognitive and psychological tests. Today, we are collecting data from patients at a pace never encountered before, and progress in the way the datasets can be analyzed suggests that psychiatry is on the brink of a transformation, similar to the one we have seen in oncology.

In the development programs underway at the company where I work, we try to go full circle with our programs, since this is necessary to achieve the desired benefits for patients.

It is of course commendable to try to identify subsets of patients with biological commonalities as some of the colleagues in the precision field are doing since this can be the start of new development programs that will allow for more specific treatments and better outcomes in subgroups of patients.

As an example of what we do, in one of our programs, we have started with the insight that a subgroup of about 30 percent of depressed patients have a disturbance in the stress management system, sometimes referred to as the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenals axis (HPA axis). This is the signaling system used by the brain to direct the production of the human stress hormone cortisol from the adrenals. In healthy individuals, this system is in a fine balance with feedback mechanisms that prevent it from being activated for a long time. However, in the subset of depressed individuals with a disturbance, the system is hyperactive and relatively insensitive to feedback inhibition. It is believed that the hyperactivity is caused by an increased signaling by vasopressin, a small peptide hormone. Thus, we have an understanding of the disturbance and would like to have a tool to overcome it.

Since hyperactivity of vasopressin has been implicated as an important part of the problem, it is natural that inhibitors of vasopressin have been developed by the pharmaceutical industry. Such were in clinical development more than a decade ago but did not convincingly show a benefit, despite some clinical data showing statistically significant efficacy. Since the disturbance appears to occur in less than a third of the patients included in these studies, it is not so surprising that efficacy signals were diluted by patients who had no problem with the HPA axis. Thus, there is a tool to overcome the disturbance, if only the appropriate patients could be identified.

The hyperactivity in the HPA axis can be identified using a physiological challenge test, which however is too complex to introduce in normal clinical practice. A research team at the Max-Planck Institute in Munich nevertheless conducted the physiological challenge test in a large group of depressed individuals and could identify the subgroup with signs of HPA-axis hyperactivity. Thereafter a genetic signature that was seen in this subgroup was identified. It is based on several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and is a genetic test that can be conducted after a single blood draw, and easily be included in normal medical practice. Thus, now there is a way to find the patients that should benefit from the intervention.

Therefore, we are now going full circle, evaluating the efficacy of the vasopressin V1b inhibitor together with the genetic test in a clinical trial with depressed individuals in eight European countries.

We aspire to not only identify a novel treatment with meaningful benefits for a subgroup of depressed individuals but also to demonstrate that psychiatry has finally entered the precision medicine era.