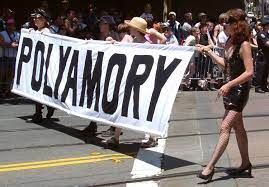

Polyamory

Consensual NonMonogamies and Pride

Why visibility matters for CNM and LGBTQ folks.

Updated June 29, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- The movement for gay pride accelerated in 1969 with the Stonewall riots, which Pride parades commemorate.

- There are controversies over who belongs at Pride, and if CNM counts as queer or not.

- Public visibility brings both awareness and maybe protection, but also backlash and discrimination.

- CNM communities are gaining more public awareness with events like the Day of Visibility on July 15.

In honor of LGBTQ+ Pride month, we breifly interrupt the Untangling NonMonogamies series to explore the origins of Pride celebrations, consider who is welcome at Pride, and the intricacies of Pride, public visibility, rights, and backlash.

The Origin of Gay Pride Celebrations

Pride celebrations grew out of the Stonewall riot in June 1969, when patrons of the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, Manhattan, tired of frequent police harassment and counter-attacked a group of officers who had come to abuse and arrest the Inn’s patrons for their “disorderly” conduct of dancing, kissing, and wearing clothes of “the opposite sex.” Decades of constant raids and beatings had worn thin, and Stonewall patrons fought back in the streets around Christopher Park for six days.

Modeling their protest after BIPOC communities' bid for civil rights — the template for social liberation action in the United States — the Stonewall riots galvanized gay people to build their nascent liberation movement into a larger and more organized effort to draw attention to police abuses and social oppression. Gay people in larger U.S. cities began holding more protests, marches, rallies, and sit-ins to highlight the damages of homophobia and demand fair and just social inclusion.

Who is allowed at Pride?

Over the last 50-plus years these early protests have expanded, and what started as pushback against commonplace abuse of power in New York City has since grown to a celebration of gay pride across the globe. Gay people around the world have made some inroads in gaining access to the same human rights granted to cisegender heterosexual men. With this increased attention and success for some aspects of the gay liberation movement, over the years conservative voices have arisen to decry how bisexual, transgender, kinky, and other more marginalized populations should not be included in Pride celebrations because they make the rest of “us” look bad. This shrinks the definition of who counts as “us” to a select group of gays who decide that they are most palatable to mainstream conservatism. Worse, it ignores the fact that the bravery of gender-nonconforming Black and Latinx patrons of Stonewall like Marcia P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera in the face of police brutality that sparked the entire Pride project.

Pride and CNM

The question of who is welcome to attend Pride celebrations and function as a public face of the LGBTQ+ community for the rest of the world remains fraught with infighting. Some people take a “big tent” approach and include all sex and gender minorities under the largest possible umbrella of relationship, gender, and sexual nonconformity. Others prefer a more selective approach, perhaps fearing that either their smaller group will be overshadowed and diluted in the larger group, or that some of the members of the other subcategories have public personas that are politically disadvantageous for those who wish to fit in more seamlessly with mainstream society.

Are CNMsters welcome at Pride? Do polys count as queer?

Are people in consensually nonmonogamous relationships welcome as celebrants of Pride? It depends on who is asking and who is answering. At the most surface level, everyone who wishes LGBTQ+ folks well is welcome to celebrate as an ally. The issue of attending as a member of the LGBTQ community rests on one's definition of Queer.

Are CNMsters queer? Again, it depends on who is answering and what kind of CNM. Mainstream swinging communities in the U.S. are decidedly not queer, and are in fact known for their strong emphasis on heterosexual or “girl on girl” sexuality and prohibition of male same-sex play among their enthusiasts. Among polyamorists and relationship anarchists, however, same-sex relationships (again, more so among women but not exclusively) and gender nonconformity are routine, meaning those folks might be attending Pride primarily as nonbinary or pansexual persons, while their CNM identity might feel less relevant or important. Research shows that higher proportions of LGBTQ+ populations engage in CNM relationships than do heterosexuals, in part because being lesbian/gay/pan/bi is already branching into sexual or relational non-conformity so why not check out CNM too?

Public Visibility

Aside from the controversies of who counts as queer or who is welcome to march in Pride parades, the underlying issue remains that visibility means taking up public space, and gaining public awareness can help produce accommodations like protection from discrimination and the ability to marry a partner of the same sex. LGBTQ+ pride visibility also gets backlash, like people trashing displays of pride merchandise in big-box stores and state laws targeted at removing access to healthcare based on gender assigned at birth.

CNM is also increasingly taking up public space, which is both politically advantageous and disadvantageous. Greater recognition leads to more awareness and inclusion, but it also leads to more surveillance and control. So far, many CNM families have been largely invisible, anonymous among the ranks of divorced or separated families that have multiple adults, ex-spouses, and new partners clearly evident in children’s lives. Once there is more attention to CNM families, however, they will also be a larger target for retaliation and discrimination, as we have already seen when some polyamorous folks have lost their jobs, kids, and housing.

Brett Chamberlain, chair of the board of directors Executive Director at OPEN (Organization for Polyamory and Ethical Non-monogamy), thinks that the potential drawbacks of visibility are worth it – for some people. Those who are safe to do so can, and maybe even should, come out because it raises awareness and possibly eventually legal rights and protections for people with less social privileges as well. Chamberlain opined: “People struggle to accept what they don’t understand, and it’s hard to understand what you don’t see. Just as with the gay liberation movement of the 70’s onward, the best way to push back against stigma is to help people understand that people from all walks of life practice non-monogamy. We’re your neighbors, your coworkers, your family...in your office, in your church, everywhere you look.”

Building on the strategy of linking visibility with rights and legal protections, groups from across the CNM movement are planning a Day of Visibility for Non-monogamy on July 15, 2023. More than three dozen organizations have signed on as participants in this day of action, which includes posting graphics on social media and planning local events where people can meet each other to share information, support, and CNM pride.

References

Pallotta-Chiarolli, M., Sheff, E., & Mountford, R. (2020). Polyamorous parenting in contemporary research: Developments and future directions. LGBTQ-parent families: Innovations in research and implications for practice, 171-183.