Relationships

Common Interaction Patterns Among 3 People

Several patterns tend to repeat in interactions among groups of three.

Posted September 27, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Georg Simmel identified social geometry as common patterns among three people, groups, or entities.

- Threesomes can be all for one, two ganging up on one, or one between two.

- Interaction dynamics can change over time and cross these categories.

This second blog in a series of three explores common patterns that appear when three people interact. The first blog in the series explained why threesomes are the most common form of consensually nonmonogamous group relationships. Interactions among three entities—individuals, groups, institutions—are incredibly common. From two older siblings ganging up on the youngest one to the “theater geeks” and the “stoners” creating an informal coalition to prank the “jocks” in their high school or the United States attempting to broker a peace deal between the Israelis and the Palestinians, common patterns of interaction appear between three units.

In 1890s Berlin, foundational sociologist Georg Simmel hosted cocktail parties and salons where he would observe interactions among the partygoers. Through decades of such observations, Simmel developed his ideas of social interaction on an interpersonal level and created theories about those at the larger social level, including topics like money, fashion, games, and the social life of urban centers. Many of Simmel’s ideas explore social distance and placement, which he called social geometry.

Social Geometry

Simmel’s systematic observations allowed him to identify patterns that later scholars have found useful in other settings—the theoretical version of replication of results. These patterns reappear so often that they function almost as archetypes for interaction, not only among individuals but at every social level.

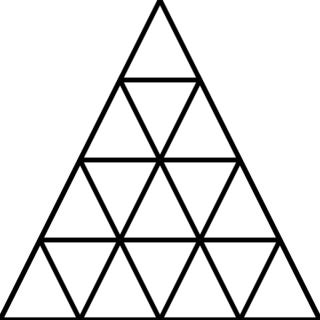

Patterns among three entities take several primary forms: all three united together, two forming a coalition against the remaining one, or one mediating between the other two. If one person leaves the triad, it becomes a dyad; if two people leave, it dissolves completely.

When all three entities are together, they strongly align their ideas, behaviors, and goals.

Triadic social interactions can also produce a dynamic of two against one. In those cases, two of the three collaborate to present a united front against the remaining person with whom they are at odds. In other cases, one member of the threesome will mediate between the other two.

This dynamic appears when there is some conflict between two members of the trio, and the member who has little or no disagreement with either of them (around that specific issue) will act as a conduit for the quarreling members’ communications in an attempt to help them understand each other and reach some agreement.

Polyamorous Applications

These triadic dynamics will vary tremendously in consensually nonmonogamous (CNM) relationships, depending largely on the type of CNM, the people involved in the interactions, the boundaries they have negotiated, and the distribution of power within the threesome.

The dream for many polyamorists is the three-for-all dynamic when every triad member shares a strong agreement about boundaries and goals, and all are equally invested in the long-term well-being of the relationship and its members.

While that level of connection and agreement can be delightful, it can also be quite challenging to establish and sustain—especially if two members of the threesome had an established relationship before connecting with the third.

When two people are together already and then meet a third person, there is almost always a power imbalance, with the two longer-term folks having a stronger coalition than either of them does with the new person. This can contribute to a two-against-one dynamic, in which the established couple has more united power than the new person who entered to create the threesome.

Polyamorous community lingo deems that dynamic couple’s privilege, in which the couple is assumed to be the most important social entity. The third person must follow the couple’s rules and remain disposable if the couple feels threatened.

Some triads create an alternative to the two-for-one dynamic, in which both members of the pre-existing relationship focus on the third person who has joined them. When done manipulatively to get the third person to bond with the existing couple and forsake outside connections, that joint attention might be better understood as love bombing. If it is an authentic attempt to honor and celebrate the newcomer, then a two-for-one dynamic can spur the transition to three-for-all.

Another common expression of the triadic dynamic among polyamorous folks is the one-between-two interaction in which one partner wants to be with two other people, but those people are somehow at odds with each other.

This middle partner—termed the hinge in poly lingo—will often end up in the position of translating one partner’s communications, boundaries, wishes, schedule, or feelings to the other partner and then doing the same thing in reverse with translating the recipient’s response.

Done manipulatively, the hinge distorts information in translation to control the situation. More often, at least in my research data, the hinge feels caught between the two partners, buffeted and pulled rather than in control of the interactions. In many resilient polyamorous relationships, the two partners of the hinge establish a friendly relationship in which they can communicate directly if needed.

Sometimes these partners develop polyaffective relationships, coming to see each other as chosen family members like a sibling, dear friend, and/or co-spouse. Over the years, several of the polyaffective triads in my longitudinal study have transitioned from a congenial one-between-two to a three-for-all dynamic without the sexual relationships changing at all.

With its drive to expansive emotional and sexual intimacy combined with the (comparative) ease of creating groups of three, polyamory lends itself especially well to creating triads. However, most triads in my longitudinal research do not match cultural expectations of what a threesome looks like, and the next and final blog in this series explains why.

References

Spykman, N. J., & Frisby, D. (2017). The social theory of Georg Simmel. Routledge.