Relationships

Learning Love and Loyalty in the AIDS Crisis

Personal Perspective: How caring for a former beau taught me what matters most.

Posted April 20, 2024 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Even a difficult romance can lead to a great friendship.

- Love leads us to do what needs to be done for a loved one simply because it's required.

- Putting aside self-interest can let love shine through.

David called me on Saturday, April 23, 1994, to tell me Bill died that morning at 8:35. Now it was over. The inevitability, the feelings of resignation, concern, fear, and despair would all merge into a sense of great loss.

Mostly, I felt calm, even numb. I was glad to know Bill died peacefully and not in pain and that he didn’t suffer a long decline. “But goddamn it!” I wrote in my journal that day. “This was a man I loved a great deal—more than I’ve ever loved another man in a lot of ways.” He was the “icing on the cake” when I decided to move to Washington. He vexed me by breaking up with me regularly and keeping me always guessing what he felt for me. He hurt my feelings greatly at times with unchecked comments.

But we also became great friends and colleagues who delighted in each other’s successes. He told me while he was sick how proud he was that we were colleagues. Coming from a man so highly regarded for his hard work and effectiveness, I took it as a high compliment.

In many ways it was remarkable Bill had survived even this long. He had virtually no immune system to speak of. He’d had pneumocystis pneumonia, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and, most recently, had an IV permanently implanted in his arm to treat cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis. Now, he had brain lymphoma. When David called me with this particular news, we agreed Bill’s seemingly rapid decline could ultimately prove to be a “severe mercy,” to borrow C. S. Lewis’s words, if it meant less pain and suffering and deterioration. Bill had told David the one thing he could not bear would be to become demented.

So we kept our vigil. I visited Bill nearly every day after work while he was at George Washington University Hospital during those tough weeks. Because I arrived around suppertime and Bill became unable to feed himself, I fed him his food. I brought in my electric razor and shaved his face; I knew Bill would want to be clean-shaven.

The clashing images of those April days made for hard emotions and jarred my soul. Evenings, I sat with a young man slowly dying. By day, bright, happy daffodils smiled in the sunshine and danced on the breeze. I felt sad and frightened at the thought of what horrors might yet lie ahead for the man I still loved, even after all this time. Yet I was also aware of a strength within me that enabled me to go to Bill’s hospital room each day after work and simply be there, even when he was mostly asleep.

Witnessing Bill’s decline was the closest I have been to anyone at that extremely advanced stage of HIV disease. I was struck by how terribly grown-up I felt during this ordeal. I knew from my experience of so many losses by then that, awful as it feels, I had to go on anyway. That was what I had learned about post-traumatic growth and resilience even by then. I wrote in my journal, “There’s something almost refreshing about thinking of Bill’s comfort, something that takes me out of my self-interest and self-pity. This is love, I recognize it, and I am serenely happy to know that after eight and a half years of knowing Bill, I am at this place where I love him in such a way as to have no expectations at last, and want only to give of my strength and life to him in his direst hours.”

During his last good weeks Bill and I talked about everything that seemed to be important between us. One evening he kept repeating over and over, “I really do love you.” Was his mind still intact? I wondered. I chose to believe that he was rolling over the thought in his mind, coming at it from different angles and trying to convince me, at last. Or maybe he was astonished that, in the end, it was, after all, true. Either way, we were making our final peace with each other. Our tumultuous years were far behind us. We had moved far beyond mere forgiveness.

In the grand lobby of the American Psychological Association’s office building on Capitol Hill, on Tuesday, May 17, 1994, men and women in dark suits gathered to pay their respects to “the father of the HIV prevention lobby in Washington,” as Bill was described. It looked, for all intents and purposes, like another Washington cocktail reception—like the many Bill had attended in his roles as a co-founder of the National Organizations Responding to AIDS (NORA) coalition and as a board member of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

Everyone was there to honor Bill: members of Congress, hill staffers, scientists from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health, the national LGBT political groups, and a range of national organizations. Rep. Nancy Pelosi, the future speaker of the House, spoke for many when she said, “I can’t find words to say what a loss it was. He was such a happy soul, and persistent. So many lives have been saved because of his work.”

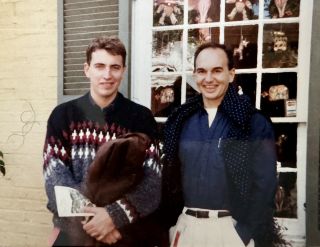

I stood off to the rear of the crowd, listening to the tributes to Bill Bailey, the gay activist and brilliant HIV-AIDS lobbyist. I shook hands and exchanged hugs with friends and colleagues, some I had known for years, most of whom likely didn’t know my history with Bill. In my mind, I sorted through mental snapshots of Bill in earlier, happier times—times like our first visit to Waterford, Virginia, the annual house and garden tour on my thirty-third birthday in 1991, captured in the photograph of the two of us that ran with my Washington Post HIV coming-out story 15 years later.

I remembered a Bill Bailey few of these people knew. He was a gentle soul who loved folk music and A Prairie Home Companion, and in his best Garrison Keillor voice, would call me “you wonderful man.” A man-boy curled up in my arms, asking if I would protect him when he was scared. A man who left a mark on others and whose belief in me I still strive to live up to. “Billy,” I thought to myself. “You broke my heart all over again.”

References

Adapted from “The Cruelest Month: Watching the Man I Loved Die,” in Stonewall Strong: Gay Men’s Heroic Fight for Resilience, Good Health, and a Strong Community (Rowman & Littlefield).