Psychopharmacology

Heart Damage and Brain Damage

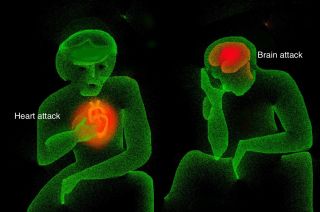

Personal Perspective: How brain attack (psychosis) is similar to heart attack.

Posted March 16, 2024 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Co-authored with Henry A, Nasrallah, M.D.

When I was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 21, I was absolutely convinced that nothing was wrong with my mind. I had been an honors student at the University of Southern California studying biochemistry. In my last year of college, I failed all my fall semester classes. I told myself I was not trying enough and that I could certainly do it again if I tried harder.

But plenty of other warning signs were present. I lost my dorm room and became homeless, meandering around the university campus, completely cutting my loving family along with many friends out of my life. Often sleeping in the always-open library, I showed the staff my expired university identification but never disclosed that I was not a current student.

In January 2006, I began to hear voices. I started hearing a chorus of voices mocking me inside my mind. A few days later, I thought three men were watching me through a window while I was showering, but when I got out of the shower to see them, I found no window. My auditory hallucinations became more intense over many months before bizarre behavior (screaming, shouting profanity, and walking in strange zig-zag patterns) landed me in a psychiatric hospital after being arrested by the police.

When I was diagnosed in the hospital, I thought of schizophrenia as a personal problem, as though it was associated with a “weak personality.” I believed I was too smart, too strong, and “too normal” ever to be mentally ill. I did not know that schizophrenia involves several neurochemical changes (including dopamine, glutamate, and serotonin) as well as dysplasticity and brain tissue loss in several brain regions. It is a serious and complex physical brain condition that affects 1% of young people, usually between 16-25 years (1).

During my first hospitalization, I refused to take medication. The main reason was my unshakeable belief that I did not need it, but I was also afraid of side effects. What I did not know back then was that antipsychotics were the key to enabling me to get discharged from the psychiatric hospital and restore my freedom to live in the community with healthy people.

My first antipsychotic medication only partially reduced the voices I was hearing in my mind, which left me thinking it did not work at all. But I was wrong. While taking medication, I found myself able to ignore the commands of the voices and not follow their prompts to shout profanity (which I had never used in my life prior to the voices.), walk in strange patterns, or hit myself. Because the medication put me in control of my behavior again, my doctors felt I was ready for discharge. I left the hospital and flew to Cincinnati to recover in my parents’ home.

Despite my hallucinations and delusions, I still did not have insight that I was mentally ill, and I believed the medication did not help at all. Then, the side effects appeared. I experienced muscle rigidity, akathisia (extreme restlessness), a voracious appetite, a blunted affect, and excessive sleep (16 hours or more a day). It seemed that even some types of chemotherapy would not be worse than taking the medication. But I was wrong again.

About a week after I discontinued my medication, the command hallucinations, which had been suppressed with antipsychotic medication, returned. I found myself shouting profanity again and hitting myself. After my voice led me to break a valuable violin, which was my most cherished treasure, I was rushed to the hospital. And I then realized that being confined in a mental institution was worse than taking the pills.

With the goal of never being hospitalized again, I became convinced I must adhere to antipsychotic medication. I would be hospitalized one last time a year later, in 2008. Still, over the past 16 years, after my new psychiatrist started me on the most effective antipsychotic drug that works when all others fail, my psychosis completely and permanently disappeared. I have been living in full recovery ever since.

I returned to college, graduated with honors in molecular biology, and then published a book about my re-recovery journey. My psychiatrist and I established a nonprofit foundation to advocate for the seriously mentally ill and to educate patients, their families, and mental health professionals.

I understand why newly diagnosed people with schizophrenia initially discontinue medications. The vast majority have “anosognosia,” which is a condition where they are entirely unaware that they are seriously ill (2). And it is certainly difficult to take a medication with side effects when you don’t believe you even need it.

When I was rehospitalized after breaking my violin, my doctor explained to me the risk of a “brain attack,” though he did not use those exact words at that time. He told me that every time a person discontinues an antipsychotic medication and relapses into another psychotic episode, more brain damage occurs.

Additionally, if one stops, relapses, and then restarts an antipsychotic medication, there is a high chance that “treatment resistance” will develop, and the medication will not work as it did before, even at higher dosages. These two factors (loss of brain tissue and loss of medication efficacy after multiple recurrences due to non-adherence) are what often lead to chronic disability in schizophrenia.

Suppose people with schizophrenia who have just experienced their first psychotic break could be convinced to always take the pills or consent to long-acting injectable antipsychotics (which eliminates the need to take daily pills). Their chances of sustained recovery and returning to their baseline are significant in that case. Unfortunately, pills continue to be prescribed, and the vast majority of people discontinue their medications and suffer multiple psychotic relapses (3).

When a person experiences myocardial infarction, or what is generally referred to as a “heat attack,” most will radically change their lives. This may involve stopping tobacco and drug use, exercising regularly, adopting a healthier diet, and taking various medications to reduce risk factors and various other lifestyle changes.

My psychiatrist, who brought me to full recovery in 2008, called psychotic episodes “brain attacks” because, like a heart attack that destroys part of the heart myocardium, a psychotic episode damages the structure of the brain (4, 5). That’s why people with schizophrenia, with the help of their psychiatric physicians, must do everything in their power to avoid another “brain attack” and avoid further brain damage that can lead to functional disability (6).

I am very familiar with the antipsychiatry movement, where people with schizophrenia are invited and sometimes even pressured to discontinue medication. But I will never go off my antipsychotic medication ever again. Today, I understand the devastating personal consequences of risking another “brain attack.”

Had I lived in the United States a hundred years ago, I most likely would have spent the entirety of my adult life locked up in an institution. But today, antipsychotics have enabled many people like me who would have been institutionalized permanently to be set free and to live a life of joy and purpose.

It is imperative to educate patients about the risks of a “brain attack,” which are likely if they discontinue their antipsychotic. For me, realizing that I would always return to the hospital if I went off meds was a life-changing realization and milestone.

I am grateful that I do not live at a time in history when there would have been little hope for recovery. Today, I hope to encourage more persons living with schizophrenia to understand that antipsychotic medication cannot only enable them to live outside a hospital but can enable sustained recovery and a new start, which may include work, school, volunteering, and meaningful relationships. Undergoing medication trials to find the best medication with the fewest side effects can be discouraging and difficult. But for me and countless others, it has been incredibly worth it.

Today, I am grateful to be living a wonderful new life, thanks to effective medication and faithful treatment compliance.

Henry A. Nasrallah, M.D. is professor emeritus of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the College of Medicine, University of Cincinnati.

References

1. Nasrallah HA and Smeltzer DJ: Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Schizophrenia. Handbooks in Healthcare, Newtown, PA 2011

2. Nasrallah HA: Is anosognosia a delusion, a negative symptom or a cognitive deficit? Current Psychiatry 21: 6-9, 2022

3. Morken G et al: Non-adherence to antipsychotic medications, relapse and rehospitalization in recent-onset schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 30: 8:32, 2008

4. Vita A et al: Progressive loss of cortical gray matter in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of longitudinal MRI studies. Translational Psychiatry 2012.

5. Torres U et al: Patterns of regional gray matter at different stages of schizophrenia: A multisite, cross-sectional VBM study in first-episode and chronic illness. Neuroimage:Cliical 12: 1-15, 2016

6. Nasrallah HA: For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry 16: 4-7, 2017