Bias

Scientific Bias in Favor of Studies Finding Gender Bias

Studies that find bias against women often get disproportionate attention.

Posted June 23, 2019 Reviewed by Devon Frye

My prior two posts reviewed every study I could find addressing the issue of gender bias in peer-reviewed science. The first one laid out some general principles and pointed out that the answers provided were a bit more complex than one might assume or expect. The second listed and briefly described every study of gender bias in peer review that I could find. (If you want details, including full references for the studies referred to here, please go to my second essay here.)

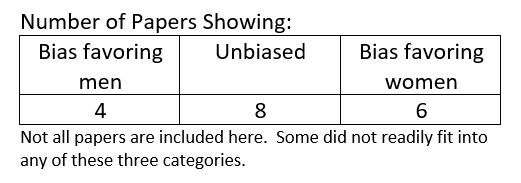

The key findings from that second essay are that there was far more evidence of egalitarian or pro-female bias than there is of pro-male bias. Those findings were reported in several summary tables, and you can refer to that essay for more, but here is one:

This essay explores a related issue. Although there is evidence of bias against women, there is more evidence that peer review is unbiased and/or favors women. Nonetheless, much of the discussion and rhetoric, even among scientists, emphasizes bias against women. Many physicists are certain that pro-male bias is a serious problem. So is the American Association of University Women. So were many of the attendees at the conference sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, as I reported here and here.

"The University of Oregon is arguing in court that there is no gender bias in STEM anymore. I am embarrassed to work for people who would stand behind this." This is a quote by a prominent social psychologist on Twitter, with a link to yet another academic appalled at such a suggestion.

Why is there such rhetoric and such certainty? There may be many explanations, but the one I explore here is bias. Not gender bias, but scientific bias. In short, it is quite clear that papers finding bias against women receive more scientific attention than do papers finding no bias or biases favoring women. Let's explore the evidence for that strong claim.

Background: The Political and Methodological Dysfunctions of Social Psychology

Social psychology is riddled with all sorts of biases and dysfunctions. You can find an introduction to political biases in some of my earlier blogs here, here, and here. See also this book on the wild overselling by social psychologists of "narratives of oppression" such as the supposed (but not actual) power of self-fulfilling prophecies and inaccurate social stereotypes to create social realities; see also this compilation of articles revealing how political biases or social justice activism has led to all sorts of distortions. You can also go to my publications page, which has links to many such articles.

Independent of political biases, social psychology is in the midst of what is sometimes called a Replication Crisis, but which, in my opinion, includes dysfunctions that go way beyond replication.

In this paper, we do a forced march through large swaths of social psychology to show how, even when research is replicable and has not used questionable research practices, the conclusions reached can still reflect unjustified interpretations. Those biases are often not political, and instead often reflect theoretical biases or researcher desires to produce a "wow!" effect (some dramatic supposedly world-changing finding. Few, if any, turn out to be true).

One crucial quality control is sample size. Although the sample size is not the only indicator of the quality of a study, it is an extremely important one, as psychological science reformers Fraley and Vazire described in this paper:

"But if an overwhelming proportion of published research findings are not replicable simply due to power issues (i.e., problems that are under the direct control of researchers and the editorial standards of the journals in which they publish) rather than the uncertainty inherent in human behavior, then people have little reason to take psychological science seriously. In short, compared to journals that publish lower powered studies, journals that publish higher power studies are more likely to produce findings that are replicable—a quality that should factor into the reputations of scientific journals."

Power is a technical statistical term, but, oversimplifying only a little, refers to how capable a study is to hone in on the effect under study. In many studies, power is mostly determined by sample size. This is probably consistent with most people's intuitions about science with human participants: All else being approximately equal, studies with larger samples produce more credible, valid findings than those with smaller samples.

Citations as a Measure of the Impact of a Scientific Paper

Fraley and Vazire's N-Pact factor offers a lens through which to view scientific bias. Do scientists tend to give more credit and attention to studies with large or small samples? One measure of credit and attention is citations. The more work is cited, the greater impact it has had; this is so important that universities have used citations to create all sorts of indices intended to capture how influential their faculty are.

First, some exclusions. Even influential studies take some time to percolate through the scientific community (if, e.g., a study is published in 2016, only papers after that have much of an opportunity to cite it, and many studies take years from idea to publication, so impact cannot readily be evaluated in the first few years after a study has been published. Therefore, I excluded all studies of gender bias in peer review that were published 2016 or later. Put differently, I only included studies if they were published 2015 or earlier. Although I found 18 papers assessing gender bias in peer review, seven were 2016 or later and were excluded. In addition, one (Moore, 1978) was quite old and also had a result I was not sure how to categorize (ingroup bias, men favored men and women favored women). This produced no net bias but it did not seem right to describe this study as finding results that were "unbiased" so I excluded it as well, leaving 10 papers. If you go to my prior essay on this, you will find the 18 studies; remove Moore (1978) and the seven that are 2016 or later, and you will have the pool of 10 included here.

Results

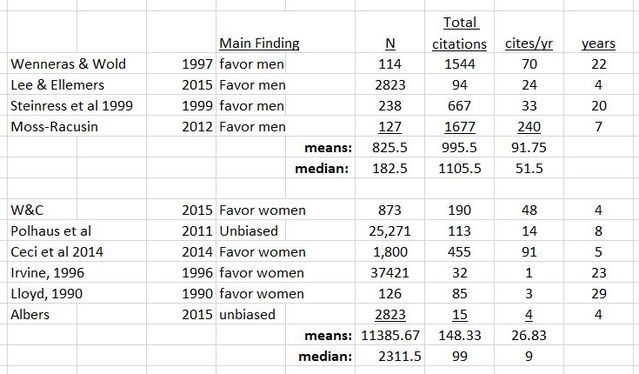

I then tallied the main result, the sample size and citation patterns for each of the 10 studies, as reported here, through yesterday (June 22, 2019):

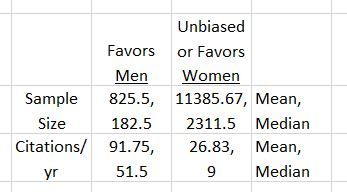

Lots of information there, and I want to be completely transparent how I did this. This table, however, nicely summarizes those data and constitutes key results:

Two things should be immediately and vividly clear from this. The studies showing peer review is unbiased or favors women:

- Tend to be based on much larger samples than studies showing biases favoring men (mean/median sample sizes of 11385.67 & 2311.5 versus 825..5 & 182.5

- Tend to be cited at much lower rates than studies showing biases favoring men (means/median yearly citation rates of 91.75 & 51.5 versus 26.83 & 9.

The overall correlation between citations/year and sample size is -.36 (smaller studies are cited more frequently). Fraley and Vazire (2014) used this type of information to characterize the quality of journals. If used here to characterize the quality of individual articles, by this standard, the quality of articles showing bias favoring men is considerably weaker than that of articles showing peer review is unbiased or favors women.

This can, perhaps, be most easily seen by direct comparisons of pairs of articles that are highly similar in some respects (year of publication, the journal published in, etc.).

For example, both Lee and Ellmers (2015) and Albers (2015) were published in the same year and in the same journal. The only difference is that Lee and Ellemers found gender bias, but when Albers reanalyzed their data, he did not. Consistent with the general pattern, Lee and Ellemers has been cited 94 times, Albers only 15, meaning that at least 79 articles have cited Lee & Ellemers without even mentioning Albers' reanalysis.

Similarly, both Moss-Racusin et al (2012) and Williams and Ceci (2015) were published in the same prestigious journal, The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Moss-Racusin et al former had an N = 127, whereas Williams and Ceci had an N = 873 (W&C also had five studies, whereas M-R only had one). Of course, no one could cite the study until after it came out, so let's only compare citations for 2016 and later Moss-Racusin et al: 1077 and Williams and& Ceci: 156

This means that, after W&C came out, there are still over 800 papers citing Moss-Racusin et al without even mentioning Williams & Ceci.

Now, let's consider the two older experimental studies.

Steinress et al (1999) had N = 238, found bias favoring men, and is cited 667 times.

Lloyd (1990) had an N = 126, found bias favoring women, and is only cited 85 times (although this is one of the few cases where this study actually has a lower N than the bias favoring men study).

Last, let's consider the two older studies examining real outcomes:

Wenneras and Wold (1997) found bias favoring men, has a sample size of 114, and has been cited 1544 times.

Irvine (1999) found bias favoring women (in more recent data), had a sample size in excess of 37,000 and has been cited 32 times.

Conclusions

To be sure, sample size is not the end-all be-all of research quality. Scientists have every right to make an argument for why the studies showing biases favoring men are better and deserve more attention and credibility than the other studies—at which point other scientists can evaluate those arguments for their credibility. What should not be an option, however, is to simply ignore studies that do not fit one's preferred narrative or conclusions.

Overall, therefore, my prior essay indicated that evidence of biases favoring men is weak, and there is at least as much evidence of biases favoring women and unbiased responding.

This essay showed, however, that bias is alive and well, even if gender biases in peer review may be on shaky ground. The bias alive and well is a scientific bias in favor of studies showing biases against women.

I realize gender bias can be controversial. I would be delighted for you to post a comment, but, before doing so, please read my Guidelines for Engaging in Controversial Discourse. Short version: Keep it civil (no insults or ad hominem, no profanity or sarcasm), brief, and on topic, otherwise I will take your comment down.

If you find this essay interesting, feel free to follow me on Twitter, where I routinely discuss this sort of thing.