Relationships

Are You Afraid of Darkness?

Does opera have a happy ending — ever?

Updated July 26, 2023 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Claude Debussy based his 1902 opera Pelléas et Mélsande on the play by Maurice Maeterlinck. You would not describe it as the work of two happy campers. Called an overlooked masterpiece, on many levels it’s a master-mess of theatrical pleonasm (i.e. Mélsande sobbing and singing, “I am unhappy” when sobbing alone would have done the job very well), redundancy, lack of any meaningful character development and heavy-handed symbolism. So, what did polymath director/scenic/costume/projection designer Netia Jones do with the material in the new production at the Santa Fe opera?

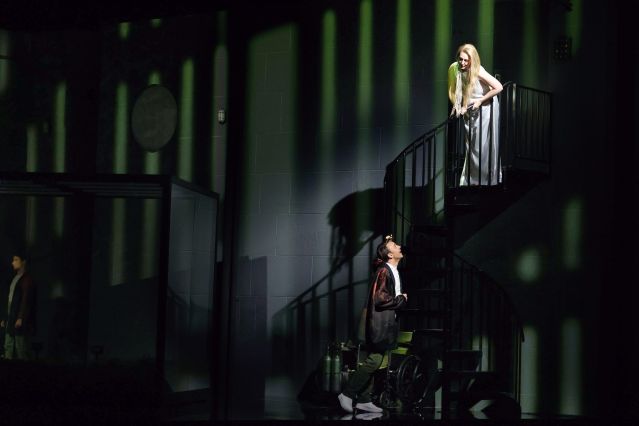

She gave the story a contemporary feel by placing it in a deterministic universe or, more accurately, multiverse. Interestingly, the characters singing onstage are replicated by non-singing doppelgängers who look and act like the characters and suggest that human behavior repeats over and over again in other times, other places. The piece postulates that we are all actors in a drama written by the hand of fate; it starts when we take our first breath and continues until our last. The characters are controlled by an ever-repeating cycle of life that spins around like the huge fans we see onstage. Just as they move air around, humans try to force fresh air into stagnant and doomed lives.

In this production, we have no free will, and nothing we do changes our destiny. From the moment we are born, we are doomed to be sad creatures who thrash around, suffer, perhaps have a few moments of happiness, and are not responsible for our actions, no matter how heinous. And like the fan blades, the story is always the same and endlessly repetitive. All we can do would be to enjoy the few moments of freedom and joy — expressed through impossible love — and know we are in the shadow of death.

You may find such a conceptual opera intriguing, or you may be repelled and search for works that offer hope, are upbeat, and entertaining. It depends upon what satisfies you in art. Perhaps you do not mind or are even attracted to dark works. They may correspond to your view of life, or they may allow you to feel your own feelings of depression, despair, and sadness in a darkened theatre space, when they are happening to someone else. There is a relief in being able to see and hear the deep unhappiness of others without having to live it ourselves. It may make the darkness in our own lives bearable.

In the story, Mélisande is a young woman who is as mysterious as she is beautiful. No one knows or ever learns anything about who she is, where she comes from, or what has traumatized her so much that she wants no one to touch her. She magnetizes men who try to control her (i.e. her husband, the hunter — and his sport defines his aggressive, hurtful, and ultimately homicidal character), vampirize her life force, or actually love her even if they know nothing about her. The opera is strewn with references to her lips, long hair, and hands, and every man wants to touch she-who-does-want-to-be-touched. Even the king, her husband’s grandfather, who is infirm, almost blind and on a fast track to death, begs to touch her, to get an infusion from her of youth, beauty, light, and innocence. He is like the blind prophets of ancient literature who see the future and know the truth, but that doesn’t stop him from wanting to get a hit of hope by pawing a young woman. In a sense, Mélsande is a tabula rasa upon which everyone projects their own needs, fears, and desires.

The plot, reduced to bare essentials, is this: Mélsande, a lost, depressed young woman hides in a dark and menacing forest and is “saved” by Golaud. He marries her and brings her home to his grandfather’s palace where she feels imprisoned in a joyless, dark, airless life. She falls in love with his brother Pelléas, and although it is never consummated, it is pure and youthful. There is hope, until Golaud kills his brother because, well, he just can’t help himself. He seems to feel guilty but then decides it’s fate’s fault. After the murder, Mélsande lies, weak and ailing, and Golaud drives her to death by hounding her relentlessly as he tries to find out if she slept with his brother. She dies. And the rest are soon to follow.

Throughout the story, a doctor is onstage, and his medicine seems largely to consist of delivering oxygen to all the characters as they descend into illness and crawl or careen towards death. There is no oxygen, no freedom, no happiness in the palace, until Pelléas and Mélsande experience their brief forbidden love before dying.

When Mélsande first meets Golaud, she observes that he has a few gray hairs. When asked where she comes from, she answers that she is cold. She comes from youth, is alarmed at aging, and feels the coldness of death in the future. She even sees a future doppelganger who floats, dead, in the water before her. It is a short leap from birth to death. And if a baby is born in light, it quickly moves into the darkness of life, the occasional sharp brightness of blazing sun, and then back into the shadows. Life to death. Light to darkness. That is the rhythm of the opera.

There are two other stories heavily referenced in the opera: first, the doomed love of Romeo and Juliet, and second, Rapunzel, the princess who lowers her long tresses to save herself and her love. In Rapunzel there is a happy ending, but for Romeo, Juliet, and the rest of us mortals, we are lost, hopelessly wandering around in a dark forest whose only exit is death.

The second half of the opera is more compelling than the first, the music is less jumpy and disconnected and more satisfyingly dramatic and dynamic under the baton of Harry Bicket. The performers are well-cast and put body, soul, and beautiful voices into their roles. But the question remains: is this how you want to spend a few precious hours of your life?

The answer depends on what you need, want, and expect from art, and how much you want to avoid darkness.