If you browse through the profiles of practicing therapists you'll find many who proudly proclaim their methods are "evidence-based," meaning the theories and techniques they use have been studied and proven effective by research trials. The phrase says they're selling a bona fide product, you can find healing with them because science backs it up.

But some in the therapy world give the stink eye to such statements. They claim the studies proving effectiveness are either biased or don't represent real-life problems and real-life treatment approaches.

If you're new to this debate, you may find it interesting that this battle often falls along party lines (yes, there are divisions within psychotherapy that often look similar to political affiliation. Sigh.). The evidence-based crew tend to hail from the Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) camp, a relatively new(er) field embraced by insurance companies because they produce a quick reduction of symptoms, requiring fewer sessions. The detractors are from the older guard, the "talk therapy" (a term I'll use here, but all psychotherapy requires talking) purists who use titles like psychodynamic, psychoanalytic, humanistic, and existentialist to describe their methods. They believe therapy is more complex than a series of techniques to minimize symptoms, it is a relationship that heals because the relationship itself provides the corrective emotional experience to allow for growth and change.

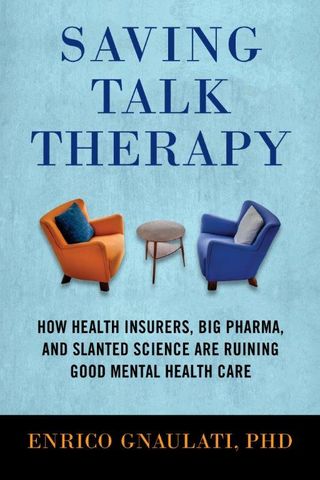

Enrico Gnaulati, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist in Pasadena, California, who adamantly falls in the latter camp, and is quite explicit in his criticism of the former. His recent book "Saving Talk Therapy: How Health Insurers, Big Pharma, and Slanted Science are Ruining Good Mental Health Care" (Beacon Press) is a manifesto of talk therapy and a call to action to protect it. He was kind enough to grant me this interview to help explain his views.

RH: Is psychotherapy dying?

EG: Dying is too strong a word. I’d say, seriously under threat; at least as it applies to varieties of talk therapy that are relatively non-directive, time-intensive, in-depth, and exploratory in nature—typically under the psychodynamic and humanistic umbrellas of care. These are the approaches where clients are allowed ample time and space to settle in and emotionally unburden themselves—to think the unthinkable, feel the unfeelable, and say the unsayable—with a therapist who truly embodies that all-important blend of empathy, patience, discernment, serenity, and forthrightness.

RH: Many therapists consider a designation of “evidenced-based” to be the golden seal of approval for their treatment approach, but you’re skeptical of this. Can you explain?

EG: It’s no secret that “evidenced-based” has become a code phrase for CBT-type, short-term psychotherapies supposedly tailored to reduce the symptoms associated with a given diagnosis. A careful review of the literature uncovers how the effectiveness of these studies has been overrated. Take Cognitive Processing Therapy, a 12-week CBT treatment for PTSD widely disseminated in the Veteran’s Administration. Drop-out rates often exceed 38 percent and upwards of one-half of those completing treatment still retain a PTSD diagnosis. Evidenced-based treatments such as these are problematic because they measure progress strictly in terms of symptom reduction over the short term, not greater social and emotional well-being over the long term.

It turns out that evidenced-based really is evidenced-biased because the bulk of current empirical evidence substantiates that “contextual factors” in psychotherapy are most predictive of positive outcome—empathy, genuineness, a strong working alliance, good rapport, favorable client expectations. And when you survey clients they overwhelmingly want a therapist who is “a good listener” and who has a “warm personality,” not someone skilled in the latest techniques. So, CBT-type evidenced-based treatments should not be monopolizing the field right now in the way they are.

RH: You come out strongly in favor of long-term psychotherapy. What’s the evidence for that?

EG: First off, the incentives in the field almost exclusively favor conducting research on short-term psychotherapies. We are oversaturated with short-term CBT-types evidenced-based treatments because they are far less expensive and logistically complicated to conduct, and because they typically last 12 weeks, not two years, can be converted into publishable studies sooner, which matters most for academic tenure.

There are some underreported, outstanding studies on long-term psychoanalytically-oriented psychotherapy that have impressive results. One of them is the Tavistock Adult Depression Study (TADS). In this study of chronically-depressed patients it was discovered that 44 percent of those receiving 18 months of weekly psychoanalytically-oriented psychotherapy at the two-year follow up had fully recovered, compared with 10 percent who had received treatment as usual (medications and/or short-term CBT treatments).

RH: You claim there’s a psychotherapy “drop-out crisis,” because studies show that over 50 percent of clients discontinue therapy before receiving 5-10 sessions. However, don’t many clients get what they need out of therapy in a few sessions?

EG: When you measure client progress not in terms of symptom reduction, but in terms of improved social and emotional well being, there really is a positive dose-response curve. In other words, the more therapy received the better clients get. Given that only about 9 percent of clients attend twenty or more psychotherapy sessions—a number which in itself is much less than what the average anxious/depressed client needs to fully recover—to me it is indisputable that we have a psychotherapy drop-out crisis.

RH: What explains this drop-out crisis?

EG: I think graduate programs are too caught up in educating and training psychotherapists to employ evidenced-based techniques, than helping them acquire the clinical relationship-building skills that enable them to effectively reach clients and keep them in psychotherapy. There’s also the matter of insurance companies under-reimbursing psychotherapy, thereby shifting the cost over to clients who deny themselves needed psychotherapy for economic reasons.

RH: Many modern therapy-seekers have come to expect a quick solution for their problems, and may balk at the prospect of a year or more in therapy. How do you teach them the benefits of long-term work?

EG: In my experience, when I come across with clients as a careful, caring, devoted listener, dedicated to their emotional welfare, who grounds the therapy in everyday talk about problems in living and existential dilemmas that are the real source of clients’ emotional suffering, questions about the length of treatment, surprisingly, become irrelevant. We forget how psychotherapy can become a cherished life support system for the self with clients whose histories of over-accommodation to the needs of others, attachment traumas, and emotional neglect deprive them of a viable self.

RH: What is the difference between the human expertise you employ with clients and the technical expertise that graduate programs emphasize?

EG: Approaching clients with human expertise means engaging the client as a fellow human being who shares the same human condition as you and whose agonizing life stories, while unique, are familiar enough. These days, early-career therapists almost have to de-educate themselves of the need to be busy and productive in the room employing techniques, just to settle in, be present, draw clients out and identify enough with their life problems and dilemmas.

RH: You claim that the individualized practice of psychotherapy is beneficial to the greater society. How is this?

EG: Psychodynamic-humanistic approaches to psychotherapy warrant special consideration for the health of any democracy because they privilege the attainment of authentic selfhood as a treatment goal—freeing participants from passive over-compliance to authority and tradition, so that they can be free to truly think, feel, and act as individuals. Democracies need large numbers of individuals—psychologically speaking—who can think and act both with and against prevalent authority and tradition. These psychotherapy approaches tend to produce such levels of psychological individualism. In-depth psychotherapy also serves as a cultural corrective to corrosive extrinsic-materialistic values because a core dimension of the work is reprioritizing intrinsic values—improving our ability to cultivate loving relationships and meaningful work, and identify and pursue sources of genuine enjoyment, as ends in themselves.

RH: What can therapists start doing today to save talk therapy?

EG: Don’t succumb to fear and accumulate training in so-called evidenced-based treatments out of some false assumption that you will be rendered obsolete, or professionally marginalized for refraining to do so. Abide by time-honored, humanistic principles and practices in the field—that are backed up by mountains of empirical evidence—and double-down on acquiring greater skill at building rapport, showing sustained empathy, and being genuine with clients as they settle in and tell their agonizing life stories in their own way, at their own pace.