Anxiety

Our Hierarchy of Needs

True freedom is a luxury of the mind. Find out why.

Posted May 23, 2012 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

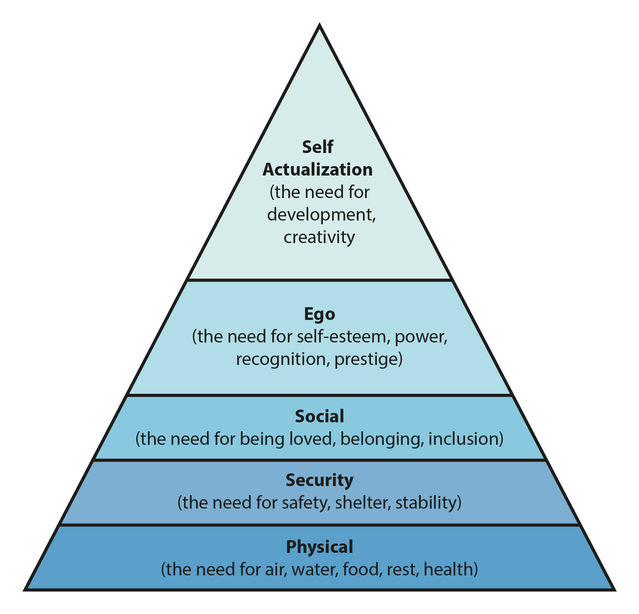

- Maslow’s so-called "hierarchy of needs" is often presented as a five-level pyramid where the bottom four levels are "deficiency needs."

- "Deficiency needs" in Maslow's hierarchy of needs do not create a feeling when they are met, but result in distress when they are unmet.

- In Maslow's hierarchy of needs, the fifth need is a "growth need" of self-actualization, or fulfillment of one's true human potential.

[Article revised on 21 October 2022.]

In his influential paper of 1943, A Theory of Human Motivation, the psychologist Abraham Maslow proposed that healthy human beings have a certain number of needs, and that these needs can be arranged in a hierarchy, with some needs (such as physiological and safety needs) being more primitive or basic than others (such as social and ego needs).

Maslow’s so-called "hierarchy of needs" is often presented as a five-level pyramid (pictured), with higher needs coming into focus only once lower, more basic needs have been met.

Maslow called the bottom four levels of the pyramid "deficiency needs" because we do not feel anything if they are met but become anxious or distressed if they are not. Thus, physiological needs such as eating, drinking, and sleeping are deficiency needs, as are safety needs, social needs such as friendship and sexual intimacy, and ego needs such as self-esteem and recognition.

On the other hand, Maslow called the fifth, top level of the pyramid a "growth need" because our need to self-actualize obliges us to go beyond our individual, limited selves and fulfill our true potential as human beings.

Once we have met our deficiency needs, the focus of our anxiety shifts to self-actualization, and we begin, even if only at a sub- or semi-conscious level, to contemplate our bigger picture. However, only a small minority of people are able to self-actualize because self-actualization calls upon uncommon qualities such as independence, awareness, creativity, originality, and, of course, courage.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has been criticized for being overly schematic, but it presents an intuitive and potentially useful theory of human motivation. After all, there is surely some truth in the saying that one cannot philosophize on an empty stomach.

Many people who have met all their deficiency needs remain unable to self-actualize, instead inventing more deficiency needs for themselves, because to contemplate the meaning of life would lead them to entertain the possibility of its meaninglessness and the prospect of their own death and annihilation.

A person who begins to contemplate her bigger picture may come to fear that life is meaningless and death inevitable, but at the same time cling on to the cherished belief that her life is eternal or important or at least significant. This gives rise to an inner conflict, and the inner conflict to existential anxiety.

Existential anxiety is so disturbing that most people avoid it at all costs, constructing a false reality out of goals, aspirations, habits, customs, values, culture, and religion in a bid to deceive themselves that their lives are special and meaningful, and that death is distant or delusory.

Unfortunately, such self-deception comes at a heavy price. According to the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, people who refuse to face up to "non-being" are acting in "bad faith" and living out a life that is inauthentic, that is contrived, constrained, and unfulfilling.

Facing up to non-being can bring insecurity, loneliness, responsibility, and consequently anxiety, but it can also bring a sense of calm, freedom, and even nobility. Far from being pathological, existential anxiety is a necessary transitional phase, a sign of health, strength, and courage, and a harbinger of bigger and better things to come.

For the Harvard philosopher and theologian Paul Tillich, refusing to face up to non-being leads not only to inauthenticity, as per Sartre, but also to pathological (or "neurotic") anxiety.

In The Courage to Be (1952), Tillich wrote:

He who does not succeed in taking his anxiety courageously upon himself can succeed in avoiding the extreme situation of despair by escaping into neurosis. He still affirms himself but on a limited scale. Neurosis is the way of avoiding nonbeing by avoiding being.

According to this striking outlook, pathological anxiety, although seemingly grounded in threats to life, in fact arises from repressed existential anxiety, which itself arises from our uniquely human capacity for self-consciousness.

Facing up to non-being enables us to put our life into perspective, see it in its entirety, and thereby lend it a sense of direction and unity. If the ultimate source of anxiety is fear of the future, the future only ends in death; and if the ultimate source of anxiety is uncertainty, death is the only certainty.

It is only by facing up to death, accepting its inevitability, and integrating it into a life that we can escape from the pettiness and paralysis of anxiety, and, in so doing, free ourselves to make, and get, the most out of our lives.

This esoteric understanding is what I have come to call "the philosophical cure for fear and anxiety."

Neel Burton is author of Heaven and Hell: The Psychology of the Emotions.