Fear

How Magazines’ Advice to Parents Has Changed Over a Century

Views of children shifted from capable and responsible to the opposite.

Posted March 17, 2022 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

I have previously written much about the decline, over decades, in children’s freedom to play and explore independently of adults and how that has contributed to well-documented declines in children's mental health, creative thinking, and internal locus of control (e.g., here, here, and here). Recently I came across a book that documents brilliantly how adults’ attitudes about children’s competence, duties, and responsibilities have changed over the past hundred years. I wish I had discovered it earlier, as it was published 11 years ago and would have been a great reference for some of my writings over the past decade.

The book, entitled Adult Supervision Required, is by Markella Rutherford, an associate professor of sociology at Wellesley College. It is based primarily on her systematic qualitative analysis of 565 articles and advice columns about childrearing that appeared in popular magazines—especially in Parents and Good Housekeeping—from the early 20th century on into the early 21st century. Here, under separate headings, are four of her main conclusions.

1. Children’s public autonomy declined greatly.

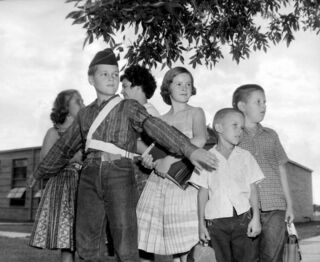

If you are considerably younger than I, you might be amazed to read articles for parents written prior to the 1970s, in which the prevailing assumption is that children, even young ones, will spend much of their time outdoors away from adults. Here are three examples from Rutherford’s book:

• An article in Parents, in 1956, expressed approval of a mother’s decision to acquiesce to her 5-year-old’s desire to walk to school by himself, about four blocks from home. The article made it clear that a child old enough for kindergarten is old enough find his or her own way to and from school and can be trusted to make that trip without an adult. The article implicitly judged the child’s desire for such independence to be healthy and normal, something the parent should encourage.

• Even toddlers once enjoyed freedom to play outdoors in the yard, without an adult immediately present. For example, an advice column in Parents, in 1946, described the case of a child “not yet two years old” who liked playing in the yard when her mom was with her but would cry and want to be taken inside if mom went in to do her work. The mom figured out that the child cried not from fear of being alone outdoors but from fear that she could not get into the house by herself if she wanted to. The problem was solved by lowering the door latch so the child could open and close the door herself. The result, according to the author, was that “now she plays happily in the yard for hours, on good days.” What I like about this example is that the solution lay not in protecting the child as if she were fragile, but in empowering her, so she herself could decide when to go out and when to come in. The mom played to the child’s strength, not her weakness. [I'm guessing that the yard was a safe one and the mom frequently looked out the window.]

• A 1966 article in Good Housekeeping proposed a set of guidelines for children’s public autonomy as follows: “A six- to eight-year-old can be expected to follow simple routes to school, be able to find a telephone or report to a policeman if he is lost, and to know he must call home if he is going to be late. A nine- to eleven-year-old should be able to travel on public buses and streetcars, apply some simple first aid, and exercise reasonable judgment in many unfamiliar situations.”

In contrast, Rutherford notes that after about 1980, articles stopped focusing on the value of children's independence and started focusing on the need to guard and monitor them. A prototypical example is a 2006 article in Good Housekeeping with the scary title, “Are You a Good Mother?” The article made it clear that the answer is “yes” if you closely watch and supervise your child pretty much all of the time.

Rutherford (2011) summarizes her conclusions regarding attitudes toward children’s public autonomy as follows (pp 61-62): “Early twentieth-century parenting advice showed evidence of a strong emphasis on children’s need to develop independence and competence apart from parents. … In depictions of children in advice texts from the first half of the twentieth century through the 1960s and 1970s, children are described as moving relatively unhindered through various public spaces. For example, children walked unaccompanied to school, roamed around and played in neighborhoods alone and in groups, rode their bikes all over town, hitch-hiked around town, and ran errands for their parents, such as going to the corner store or post office. These descriptions of freedoms to roam have disappeared from contemporary advice. Instead, parents today are admonished to make sure that their children are adequately supervised by an adult at all times, whether at home or away from home.”

2. Children’s autonomy at home in some ways increased.

Rutherford found that although children’s freedom to do things by themselves, especially things that might involve some risk, became ever more restricted at home as well as in public, there were some ways in which children gained autonomy at home. Early in the the 20th century, advice to parents often emphasized the need for parental authority over such things as what the children ate, when they went to bed, what they wore, and how they were allowed or not allowed to speak to adults in the house. Throughout the 20th century there was a gradual increase in parental permissiveness regarding these things, and advice shifted in the direction of supporting children’s rights to have choices in these personal matters. So, it is not the case that children’s freedom declined in all ways. It declined only regarding children’s opportunities to do things away from adult supervision.

3. The expectation that children contribute to home economics declined.

In the first half or more of the 20th century, parents were frequently encouraged to involve their children in regular household chores. Here's an example, from a 1946 Parents article: “The fundamental objective is to provide the child with a home, a family circle, of which he feels himself to be a cooperative member. … The more he plays on the home team—the more he runs errands for it, makes beds for it, cooks for it, mows the lawn for it, really cooperates—the more it will mean to him. Therefore, he should not be spared chores.” Toward the end of the century, however, such advice declined, as the focus turned more toward supporting children’s homework and extracurricular activities and less toward children as integral, contributing members of the family.

4. Messages regarding children’s responsibility became increasingly mixed.

Advice to parents earlier in the 20th century was quite clear about children’s capacities for responsibility. Children were largely responsible for getting themselves to places where they wanted to go; parents weren’t expected to take them. Children were responsible for their own schoolwork; parents were not homework monitors. Children were responsible to do their part in taking care of the household. They were responsible for their own choices and safety during the large periods of the day when not supervised by adults. They were seen as responsible enough that if they wanted and could secure a part-time job, such as a paper route or babysitting or mowing lawns, they could take that job and enjoy, for themselves, whatever money they earned.

Later in the century, advice regarding children’s responsibility became much more mixed. In Rutherford’s words, “Although popular advice explicitly reminds parents that it is essential to teach children to be responsible, it implicitly sends the message that parents should maintain relatively low expectations about children’s capabilities and that ultimately parents shoulder responsibility for children’s work.” As parents increasingly assume responsibility for carting their children around, helping them with schoolwork, overseeing or excusing them from chores, protecting them from real and imagined dangers, and providing spending money so children don’t have to earn their own, they reduce their children’s opportunities to develop the understanding that they are capable of being responsible themselves.

-----------

And now, what do you think about this? … This blog is, in part, a forum for discussion. Your questions, thoughts, stories, and opinions are treated respectfully by me and other readers, regardless of the degree to which we agree or disagree. Psychology Today no longer accepts comments on this site, but you can comment by going to my Facebook profile, where you will see a link to this post. If you don't see this post near the top of my timeline, just put the title of the post into the search option (click on the three-dot icon at the top of the timeline and then on the search icon that appears in the menu) and it will come up. By following me on Facebook you can comment on all of my posts and see others' comments. The discussion is often very interesting.

References

Markella Rutherford (2011). Adult supervision required. Rutgers University Press.