Chronic Illness

Art-Making and Chronic Illness

A powerful practice to enhance well-being.

Posted November 15, 2022 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

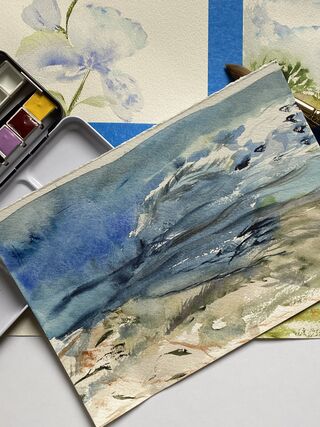

Four years ago, at the beginning of my watercolor journey, I wrote about how making art can be helpful to people living with chronic illness. In my own experience, these benefits have deepened and broadened over time, and I wondered if researchers had investigated whether and how a sustained art practice affects people living with chronic illness. Indeed, they have. It turns out that art-making affects identity and experience in ways that buffer the losses inherent in chronic illness. Broadly, art-making builds self-awareness and self-esteem, which often are eroded by illness. I highlight the specifics below.

Art-making expresses the ineffable.

The illness experience is multi-faceted, ever-changing, and profound. Words often do not do it justice. Visual art “offer[s] a bridge between the conscious and unconscious, and [is] therefore helpful for working through complex, deep seated emotions (Reynolds & Prior, 2003).” Don’t know how to say what you feel? Grab a paintbrush or clay or a piece of fabric or a camera. Don’t think too hard — just do what you are called to do. You may be very surprised by the results.

Art-making occurs in the space between agency and acceptance.

Art-making is full of choices. Color, line, shape — there are no rules except the ones you make for yourself. Simultaneously, materials have their own character and will not yield completely to the artist’s will. Watercolor, for example, is a dialogue between materials and artist, each responding to the other’s influence.

Similarly, we make choices in our lives, even as these choices are circumscribed by the ways illness affects us. We live in a space between healthy respect for those limits and an awareness that the choices we make influence those limits. We are not all-powerful, but neither are we powerless.

Art-making increases mindfulness.

One of the most pleasurable facets of art-making is that it creates a flow state, in which we are utterly engrossed in the present moment — the way releasing a bit of pressure changes a brush stroke, the way two colors meet and blend on the paper, the way we play with what is known and unknown. We notice the smallest details, we are surprised by the tiniest pleasures. We’re fully in the present moment, and our fears and worries about illness recede. We are lighter, more joyful, at peace.

Art-making contributes to a positive self-image.

Chronic illness closes and forecloses aspects of self. A social butterfly finds himself too tired to socialize. A runner no longer runs. A would-be scholar’s academic career is never allowed to begin, as her education continually is interrupted by illness. So to create art in a sustained way — to be an artist — can be a gratifying addition to a sense of self that has felt constrained by chronic illness. “What do you do? Who are you? What is important to you? How do you spend your time?” “I am somebody who makes art.”

Art-making creates community.

As we get more comfortable with making art, we want to feed the creativity we’re nurturing. Perhaps we take a class, join a Facebook group, start following other artists on social media. We go to exhibits, we talk shop with other creative people. Before we know it, we’re connected to other people who share this interest. These connections matter, especially when chronic illness has caused isolation and limited social interactions.

Art-making emphasizes process over perfection.

We keep making art because there’s always more to learn, more to express, more to accomplish. The recognition that we will never do it perfectly can be frustrating, but it’s also freeing. Instead of striving for perfection, we aim to be a little better than we were yesterday. We go through creative slumps, but we hold faith that we’ll eventually move forward by showing up and doing the work.

Similarly, living with chronic illness is process-oriented. There are periods of time when disease is relatively quiet; there are periods of time when it’s not. We learn to respect ourselves for showing up even when it’s not easy. We keep the faith even when it seems that we’re stuck in a rut.

Art-making changes you.

To be a maker of art changes how you see the world. You notice details; you’re more curious; you are engaged with both your inner world and the world around you. This artist’s mindset stays with you even when you’re not actively creating. You look at commonplace objects and think, “How might I use these items to make art?” You see leaves fall and wonder, “How can I portray motion on paper?” You admire other artwork and instantly try to decipher its artistic language: “How did the artist do that? What works for me about this piece? What am I responding to?”

In short, art making reminds us that we are active participants in life. It can feel as if chronic illness acts upon us — limiting our choices, muting our vibrancy. Art-making pushes back on these constraints, helping us reclaim agency and joy.

References

Reynolds, F. & Prior, S. (2003). A lifestyle coat-hanger: a phenomenological study about the meanings of artwork for women coping with chronic illness and disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(14), 785-794.