Education

The Majority of Girls Face Sexual Harassment with No Hashtag

The outrage over sexual harassment doesn't extend to the girls now at risk.

Posted October 30, 2017

Over the last three weeks, millions of people, mostly women, have bombarded social media with the acknowledgment that they had been sexually harassed or assaulted at some point in their lives. The #MeToo social media movement has been one of the largest trends online—over 1.7 million tweets from at least 85 countries.

For most, the reports of Harvey Weinstein’s behavior toward young actresses weren’t shocking. Few of us are aspiring movie stars, but most women can relate to that feeling of being creeped out by someone, yet not having enough power to tell him to get lost.

Our visceral familiarity with this feeling reflects a lifetime of fending off sexual harassment. Indeed, as I have written about here before (Why Title IX Matters), research shows that girls become targets of unwanted sexual attention by about sixth grade when they are barely even old enough to see a PG-13 movie. Most girls face sexual harassment, not in swanky hotel suites, but in school hallways.

Title IX used to protect them. Yet, with little fanfare, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos recently rescinded that major source of protection against sexual harassment and assault facing girls in schools. No public outrage seemed to follow.

Sexual harassment, which includes unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other unwanted verbal, nonverbal, or physical sexual conduct, begins for girls in late elementary school. By the sixth grade, more than one-third of girls have been sexually harassed by a boy, and by middle school, almost all students (95 percent) have witnessed sexual harassment happen at school. My research with Professor Campbell Leaper has shown that, by the end of high school, 90 percent of girls have experienced sexual harassment at least once, with 62 percent being called a nasty or demeaning name, 51 percent receiving unwanted physical contact at school, and 28 percent being teased, threatened, or bullied by a boy. For the girls who attend college, their risk of being sexually assaulted increases, and 1 in 4 will be sexually assaulted while in school, usually by an acquaintance.

To be sure, boys also face sexual harassment and assault, but girls’ experiences are often more severe, physically intrusive, and intimidating. The consequences for girls are especially damaging (at least compared to straight, cis-gender boys). Like the actresses who recounted their fear and anxiety after their experiences, adolescent girls report that sexual harassment leads to trouble sleeping, difficulty studying, embarrassment, anxiety, fear, depression, substance abuse, and suicidal thoughts. One-third of girls who experience sexual harassment report not wanting to go to school. Absenteeism spikes. It is not surprising that girls want to avoid the place where they are made to feel objectified, self-conscious, and vulnerable. Of course, this is the same place where they are also supposed to learn algebra and chemistry.

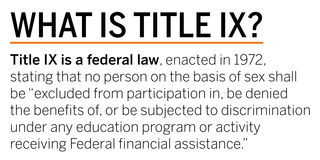

Because of the pervasiveness of sexual harassment in schools, and the lifelong damage born of those experiences, the Obama administration urged schools to increase their protection of their students. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 prohibits sex-based discrimination in educational institutions that received federal funding (and this doesn’t just mean that schools should offer girls’ volleyball).

In 2011, the Obama administration issued guidelines for implementing Title IX regulations, referred to as the “Dear Colleagues” letter, that explicitly stated that “sexual harassment of students, including sexual violence, interferes with students’ right to receive an education free from discrimination.”

In other words, since 2011, schools had to protect students from sexual harassment and assault to be in compliance with Title IX.

To do so, among other things, schools were required to investigate accusations of sexual harassment and assault, regardless of whether it was being prosecuted or not, and to determine the validity of the claim based on a “preponderance of evidence.” These guidelines are important because 95 percent of sexual assault cases by students are never reported to the police, and when reported, the cases are rarely prosecuted. Sexual assault is difficult to prove in court because it requires “clear and convincing evidence,” and even 14-year-old perpetrators know to harass and assault when no adults are present. Schools were also required to increase awareness and education about sexual harassment and assault, and to provide support services for victims, including letting a student change classes if her rapist is in her class. The law rarely protected girls, but at least their schools were supposed to (For an eye-opening description of this, read Missoula, by Jon Krakauer).

Despite the need for these protections, as of September, thanks to the long-promised actions of Betsy DeVos, those guidelines have been rescinded. Schools are no longer required to actively protect students from sexual harassment and assault. The reason for stripping away those protections was because it was presumably unfair to the accused, who according to DeVos had their lives “ruined.”

Now, with the removal of these school-based protections, victims are left to be silently victimized. The actresses victimized by Harvey Weinstein who kept quiet all of these years are no different than the girls in our research studies. Most girls simply put up with the harassment and assault. They often report trying to smile or laugh to act like it didn’t bother them, despite feeling hidden fear, anxiety, shame, and depression.

The removal of Title IX school protections reinforces an idea that girls should just smile and look pretty and let the boys in power stay in power. In the absence of national outrage or federal protections, each of us should reach out to our local schools and make sure every student, boy or girl, feels safe. Ask about what protections local schools offer to victims of sexual harassment and assault. It shouldn’t take a movie star and a social media movement for people to recognize and advocate for the safety of girls in schools.

References

Krakauer, J. (2015). Missoula: Rape and the Justice System in a College Town. Penguin Random House.