Gender

Why "Using" Gender Can Make a Big Difference Part 2

Even when we don't mean to, our words can shape children's gender stereotypes.

Posted March 4, 2014

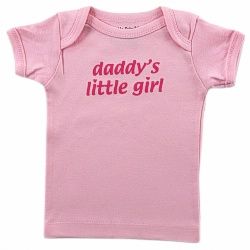

In the previous post, I tried to point out all ways that we label and sort kids based on their gender. Infants and children in preschool are the ones most likely to be color-coded and talked about with some reference to their gender. Unfortunately, this is the worst possible age to focus on gender so intensely. This is the age when children are highly focused on adults so that they can learn about the world.

Most people assume that labeling and sorting by gender doesn’t really matter, that it doesn’t lead to big differences between boys and girls, as long as you treat children equally. That argument makes sense.

We are always taught that it is how you treat a person that counts. This is a key tenet in every religious and moral code in the world, some version of “Treat others how you want to be treated” (and, of course, we all want to be treated with kindness and fairness).

That assumption--that labeling and sorting children based on gender doesn’t really matter as long as everyone is treated fairly--would hold true if children only paid attention to the more overt, obvious messages we adults send.

If children only listened to our purposeful messages, parenting would be easy. Most (but not all) parents and teachers take great effort in treating their children fairly, regardless of gender. Parents don’t need to say to their daughters, “You probably won’t enjoy math” or say to their sons, “Real boys don’t play with dolls.” Most parents wouldn’t dream of saying these blatant stereotypes to their kids. But research has shown that when we label (and sort and color code) by gender, children do notice. And it matters—children are learning whether you mean to be teaching them or not.

Someone really paying attention should ask, “How do you know that using gender to label and sort is so important to children?” In real life, it is hard to know what about gender is so important because it so ever-present in society and is something we are biologically born with. Maybe children latch onto and stereotype based on gender because it is a biological trait that is important for later reproduction and mate selection.

Carefully designed research studies have helped explain thus. In a series of studies spanning a decade, Professor Rebecca Bigler and colleagues found that children would form stereotypes about each other just like they do with gender. Amazingly, children do this even when the groups are completely made up. For example, they gave elementary school children either a blue T-shirt or a red T-shirt to wear throughout the school day for six weeks.

Teachers treated those color groups in the same ways they would use gender. Teachers said, “Good morning, blue and red kids!,” “Let’s line up blue, red, blue, red.” Kids had their names on either a red or blue bulletin board and had either a red or blue name card on their desk. But again, teachers had to treat both groups equally and not allow them to compete with one another. They simply “used” color in the same way many teachers “use gender.”

After only four weeks, children formed stereotypes about their color groups. They liked their own group better than the other group. Red-shirted children would say, “Those blue-shirt kids are not as smart as the red-shirt kids.” Just like they do with gender, they said that “all blue kids” act one way and “no red kids” act another way (this differed based on which group they were in). They began to segregate themselves, playing with kids from their own color group more than with those from the other group.

They were also more willing to help kids in their own color groups. Children walked into a classroom in which we had staged two partially completed puzzles. We had surreptitiously draped a red shirt across one puzzle and a blue shirt across the other. When given the option, children were more likely to help out the child they thought was in their group.

In all of these studies, there was always a very important control group—in addition to the group of students who wore colored T-shirts, there were classes in which the teacher who didn’t talk about the color groups. She didn’t sort by color or use the color grouping to label each child. In other words, it was like being in a class of boys and girls where the teacher doesn’t mention or sort by gender; she simply treated them like individuals. In these classes, children didn’t form stereotypes and biased attitudes about groups. If the adults ignored the groups, even when there were very visible differences, children ignored the groups too.

So what does all of this really mean? The importance of this series of studies, and why they are a staple in most developmental psychology textbooks, is that these colored-shirt groups are completely meaningless.

There is no socialization on television, no parental messages about the groups, and definitely no innate or hormonal differences that drive us to associate with only red or blue T-shirt kids. It wasn’t akin to the old assumption that boys like boys and girls like girls because they are born that way. The answer is definitely not in our biology!

Instead, it seems that children pay attention to the groups that adults treat as important. When we repeatedly say, “Look at those girls playing!” or “Who is that boy with the blue hat?,” children assume that being a boy or girl must be a really important feature about that person. In fact, it must the single most important feature of that person. Otherwise, why would we point it out all the time?

If children see a difference, they look to experts in the world (us grown-ups) to see if the difference is important or not. Don’t forget that they see plenty of differences in people. For example, they see differences in hair color. We come in brown hair, black hair, blond hair, red hair, and gray hair. But no adult ever labels this visible category, saying “Look at that brown hair kid.” “Okay, all the brown-haired kids and black-haired kids over here. All the red- and blond-haired kids over there.” Children ultimately learn to ignore these as meaningful categories, but they still notice they exist. If I ask someone’s hair color, a child can tell me. It just isn’t a meaningful category. They don’t develop attitudes about what it means to have red hair or brown hair (even the occasional blond joke isn’t constant enough for children to notice).

But with gender, children notice the difference and adults make it meaningful. Children see the category. We made sure of that with our pink or blue shirts. Also, the experts in the world, their parents, always label the category. We put a figurative flashing neon arrow on gender and say “Pay Attention! Important Information Here!” And guess what, they pay attention.

Excerpted from Parenting Beyond Pink and Blue: Raising Kids Free of Gender Stereotypes