Career

Pay vs. Flexibility: The Decision-Making Conundrum

It’s a matter of trade-offs and how much of each is important.

Posted August 3, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Many recent articles pit flexibility against pay, falsely treating them as an either/or desire.

- Many of these articles claim workers value flexibility more than pay, but these claims are unfounded.

- Workers' decisions about both pay and flexibility are made within the context of their larger life demands.

- The discussions that occur on these topics should be much more nuanced than they presently tend to be.

In the last two years, it’s been rare for a month to pass without some popular press article claiming something akin to the following: Flexibility is now more important than pay [1]. The argument is generally grounded in some recent poll or survey results, arguing that these results indicate that workers view flexibility as more important than pay when it comes to job seeking.

But the claim is flawed because it oversimplifies the potential tension between pay and flexibility, eschewing any sort of nuance in favor of clicks. But there’s nuance when it comes to this issue, some of which becomes apparent when (1) looking past the headlines and into the data, and (2) considering how both issues relate to the broader context of work-life balance.

Looking Into the Data

The evidence that flexibility is more important than pay is based on the percentage of people who indicated that flexibility was a priority when compared to those who indicated pay was a priority.

The Sherr (2022) article from which I pulled the claim above reported on a survey conducted by Microsoft. But the survey results didn’t indicate that workers valued flexibility more than pay. What it indicated was that more workers who had quit their jobs had cited flexibility rather than pay as a reason for leaving [2].

Nowhere, though, do the survey results claim that pay was less valued than flexibility. Instead, pay may be insufficient to retain some employees when they perceive a poor fit with other contextual aspects of the work environment.

Even when survey results do indicate that more workers report valuing flexibility over pay [3], this doesn’t mean workers value flexibility more than they do pay. Instead, when looking at various sources, such as Qualtrics (2022) or Chapman (2022), it becomes easy to see that workers would generally prefer greater flexibility than they currently have over a higher salary than they currently earn.

Mayne (2023) reported that 56 percent of workers would even be willing to take a pay cut to garner greater flexibility, though it didn’t indicate how much of a pay cut respondents would be willing to accept. I did find a piece by Freedman (2023), which indicated that workers would be willing to sacrifice between 2.6 and 5.1 percent of their salary for increased flexibility. But without understanding how much money and how much flexibility those folks began with, it is difficult to put those results into any sort of meaningful context [4].

The takeaway from all this, I argue, is that most workers don’t necessarily value flexibility more than they do pay. Instead, (1) they value increased flexibility instead of a pay raise, most likely only if they are earning a sufficiently satisfactory salary; and (2) when push comes to shove, some workers will choose a slightly lower-salaried position if it comes with a desired level of flexibility. But there are limits to all this, which shouldn’t be surprising because both financial resources and time and energy are important components of an effective work-life interface.

Pay, Flexibility, and the Work-Life Interface

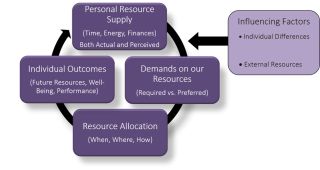

As I’ve written about in the past, money, time, and energy are basic personal resources that allow people to manage demands spanning both their work and nonwork lives (Figure 1). How well people manage their resources plays a role in how many resources they have for later, their overall effectiveness in responding to life demands, and their overall well-being.

Work is often framed as a drain on time and energy that inhibits workers from pursuing other interests [5]. In other words, the demands of work life often serve as a barrier that limits workers’ ability to allocate time and energy toward desired or required activities in nonwork life. Work also often comes with very specific time and place constraints—most workers have a schedule of some kind that requires them to be in a certain location at a certain time to allocate their energy toward demands deemed important by their employer. That means they tend to have limited control over the when, where, and how of resource allocation.

But work also provides the principal (if not the sole) source of financial resources. Without those financial resources, managing other life demands becomes impossible (as many non-work life demands require the expenditure of money). The expectation is that the employer provides the financial resources in exchange for the allocation of time and energy toward the achievement of goals that benefit the employer. As such, there is a trade-off: workers agree to allocate time and energy to an employer in exchange for financial resources (and other perks [6]).

As long as the amount of financial resources provided is considered sufficiently satisfactory to justify the time and energy they allocate toward work demands (i.e., workers earn a satisficing salary), many workers will maintain the status quo. But when a consistent discrepancy occurs one way or another, workers are more likely to be motivated to alter that status quo (Warr & Inceoglu, 2012).

In the case of pay, there are two potential issues at play, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive. First, if work demands increase (thus requiring the allocation of more time and energy) without a corresponding increase in financial resources, there is an increased likelihood that workers will find the trade-offs to be less worthwhile. This, unfortunately, has been occurring since the recession, caused by the financial meltdown (Andres, 2018), was exacerbated by the one that occurred as a result of the pandemic (Christian, 2023), and led to expectations of a Great Resignation [7].

Second, if nonwork financial demands increase such that the financial resources acquired through one’s current work are no longer sufficiently satisfactory to make ends meet, then workers may once again find the exchange to be less worthwhile. This, unfortunately, has likely been the case for many workers as a result of rising inflation.

In the first case, the issue is often one of work demands exceeding what workers consider to be reasonable given their current salary. Even if a corresponding increase in financial resources occurs, the increasing work demands may reach a point where workers would prefer either a reduction in those work demands or an increased ability to control the when, where, and how of their resource allocation toward those work demands [8]. These workers are likely the ones motivated to seek additional flexibility over increased pay.

In the second case, the issue is one of the financial resources provided by work being insufficient to effectively respond to nonwork financial demands. This can lead workers to seek alternative or, in some cases, additional employment to make ends meet (Ozkan et al., 2020, Park & Min, 2020). If they seek alternative employment, they are likely to prioritize increased pay over flexibility (Jones, 2022) [9]. If they seek additional employment, that additional employment may require consideration of flexibility in addition to pay to ensure it is compatible with the workers’ existing life demands.

The Takeaways

For as much as the media seeks to portray the pay versus flexibility discussion as a simple dichotomy, it is anything but [10]. Workers’ decisions about pay and flexibility are made within the context of their larger life demands. These life demands become a large part of their frame of reference for decisions they make about their work.

The pandemic and the prompt shift to remote work admittedly altered the frame of reference for many workers (and many employers) around the topic of flexibility (Grawitch, 2022). For many workers, flexibility has become a priority, but it doesn’t mean pay is no longer valued. But the discussions that occur on these topics should be much more nuanced than they presently tend to be.

References

Footnotes

[1] This one is specifically taken from Sherr (2022).

[2] I was unable to locate the actual reporting of survey results from Microsoft, so I’m sticking with the second-hand report of it.

[3] Most actually don’t. Instead, they show that pay is still a priority for more workers than is flexibility. In fact, I had a difficult time finding any official polls indicating that flexibility was valued by a larger percentage of people than pay.

[4] I wouldn’t be surprised to find people making upwards of $200,000/year are more willing to sacrifice a percentage of their pay than people making less than $50,000/year.

[5] This was already an issue pre-COVID, but it has become a much more common theme in popular press writings as remote work and flexibility have become more prominently discussed.

[6] Other perks like vacation time, insurance, and development opportunities become a part of this trade-off. An increasing number of workers, though, are choosing to confine the exchange strictly to financial resources by choosing to work in the gig economy.

[7] Some of those expectations came to pass, but resignations were largely limited to a few industries (Grawitch, 2022).

[8] As it could be a way to help reduce costs, such as commuting or childcare costs. This may be a strategy employed if workers don’t expect they would receive sufficient financial compensation.

[9] This is not to say flexibility would be undesirable, but that when push comes to shove, workers are likely to default to a job whose pay is satisficing, with less emphasis paid to flexibility.

[10] And I haven’t even truly scratched the surface of the issue here due to space limitations. My goal is simply to show the reader that there is a lot more nuance here than the media would like to portray.