Trauma

What Is Somatics?

Interview with somatics therapy practitioner Sumitra Rajkumar.

Posted April 5, 2019 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

I promised a follow-up on my column about somatics and trauma. Readers had lots of questions. This is Part 1 of my interview with somatics practitioner Sumitra Rajkumar. Stay tuned for Part 2, where we get nitty and gritty.

As a practitioner, how do you describe somatics to somebody who’s curious and doesn’t know much about it?

In somatics therapy, we tend to regard the body as the self. Emotions are produced in the body as sensation and interpreted by the brain as stories about how we feel. This gives us our sense of self over time. But, even that isn’t such a straightforward dialectic. Thought, emotions, and sensations are all interconnected and influence one another.

Somatics holds that many of us humans, especially in post-industrial, late-capitalist societies, mistrust our physical self and rely heavily on thinking and rumination, so we walk around in a kind of psychosomatic split, like stressed-out heads on sticks, forgetting we are part of natural life, that we have an animal life. Traumatic events or pressures in our personal history can reinforce the split and make us feel quite unsafe in our bodies too. We may have adopted survival strategies that might have saved our lives at one point but then stick around and replay in our bodies as emotional habits that make us feel limited in our choice of how to be, especially when we’re under stress. Often our emotional responses can catch us by surprise or threaten us and we become reactive and less centered in ourselves, less integrated, less intentionally us.

Somatic therapy engages all those elements through a combination of conversation, physical practice involving breath or movement and also a practitioner’s contact with the body’s connective tissues through table bodywork to open into more range of motion and mood, more choice in emotional reaction, more life.

The goal is for people to actually embody what they long to be, to be who they are more wholly, to heal that split caused by traumatic events or what can be the trauma of living in a very power differentiated society. It’s about transforming to be more alive and act more aligned with one’s values and purpose. And to do all that with a body-based intuition as well not just cognitive self-understanding.

The form of somatic therapy you practice has a political dimension. How does that work? How is it different from therapies that focus primarily on the client or family?

Politics is key to the somatics that I practice. You could call it a politicized somatics. I’ve been trained by generative somatics (lower case intentional) in the Bay Area. I get contracted to teach their courses, engage in their strategy considerations, and receive ongoing guidance and supervision from them.

The moment we have a political awareness that tells us that systemic as well as interpersonal power differentials are a key factor in the shaping of human consciousness and social relationships, then therapy itself has no choice but to adapt to that. But that awareness seems to be missing in a lot of therapy. A lot of therapy is individualistic. The message is to go it alone, go fix yourself and then return and be more useful to the social grind of capitalism. Keep that crazy away. That attitude can be tinged by a lot of sexist, racist, ableist and classist values that we embody as a society too. Therapy can be ahistorical when it focuses on the individual and the family as the only sites of shaping and transformation, rather than acknowledging the impact of society in the shaping of self and relationship.

A politicized somatics regards individuals in dynamic relationships with other humans and to social forces through history. They are connected to collective bodies that they are a part of, whether family or community or society or even larger, seemingly abstract social forces that organize how we relate like patriarchy, racism, and capitalism. I mean that the latter are not just abstractions but are very concrete in shaping people’s bodies, internal development, and their relationships, sometimes through generations.

Human beings have also shaped and created and changed society, so a politicized somatics regards the client as a social actor or agent of her own and other’s transformation, interpersonally as well as structurally. In fact, generative somatics focuses its work with people who are invested in collective action towards social justice, either as individuals or as groups and organizations, people who are accountable to one another and to change unfair practices and structures.

So much of personal trauma comes from an abuse of power—a violation of the body interpersonally, as in intimate violence or the deep stress to physical and emotional health that comes from intersections of poverty, racism, and inequality. The words “trauma” and “trigger” are bandied about a lot these days, and sometimes for good reason. Many of us are living in an increasingly traumatizing world and are more reactive and defensive within it. But we also internalize unjust social values and norms and the self-judgment or shame that can come from them and so people can also feel victimized and triggered in a way that is out of proportion to their actual access, ability, position, and agency.

In that sense, somatics is a key factor in social movement building itself. Not to be cheesy, but it really is about reclaiming hope and love in action and social movement. Like in the David Bowie and Queen song, “Under Pressure,” which I think is a great summary of somatics. “Love dares you to care for the people at the edge of the night. Love dares you to change our way of caring about ourselves.” That’s it really, isn’t it? Of course, David and Freddie would have the ultimate prayer of love.

I know learning somatics happens largely through practice—for both practitioners and clients—and I’m looking forward to getting concrete about that in Part 2 of this interview. In the meantime, how did you become interested in somatics? What kind of training was involved in becoming a practitioner?

To start off, I found myself having to learn it as part of my job. I was hired as a political education coordinator in an organization called Social Justice Leadership that trained organizers in leadership development and political strategy. They were into connecting personal and social transformation. They were also in partnership with generative somatics, which, as I’ve said, is where I got and continue to get my training and support.

Initially, I was skeptical of somatics. I was concerned it might just be some hokey New Age thing, some bland and typical Orientalist American appropriation of healing modalities from around the world. I really got hooked when I realized how deep, pragmatic and effective somatics was, how it acknowledged its syncretic and at times yes appropriative lineage, but leveraged these for change rather than being stuck and made small by those contradictions.

I noticed how much people felt impacted by the work and how it seemed to support collective group dynamics to be more communicative, less conflict-averse, more connected and resilient and therefore more brave and drama-free. We need to build democratic power in this country to push back against incredibly repressive and unequal forces in structures and in individuals who embody those structures too. We need to build each other up to embody more transformative values.

Arguably, I’m still in training. My main teachers whom I should shout out are Staci Haines, Spenta Kandawalla and Richard Strozzi, all of whom are incredible human beings and mind-blowing teachers. It’s hard for me to express how grateful I am to them. There are many others I’ve learned from and practiced or taught with. Most of us have been all up in each other’s tissues, so to speak. I’ve trained alongside them to develop my skills as a practitioner and bodyworker. I’ve also had my own one on one work with practitioners over the years and I try to stay connected through supervision. As a practitioner, I work mostly with community organizers and social justice workers. I teach generative somatics courses sometimes, but really I love to be a student whenever resources allow me to do so.

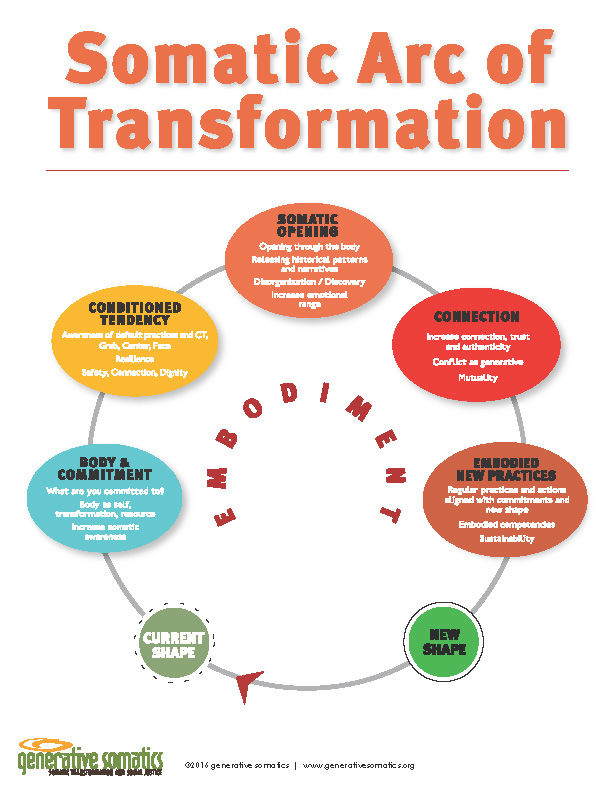

As a practitioner, I abide by key frameworks such as the arc of transformation, which leads people through a process and practice of self-awareness of default habits and conditioned tendencies and into opening and shifting towards a more intentional way of being, an embodied selfhood that is more congruent with their values and social purpose.

Centering is the foundational, building block practice of developing eased up internal room and a home base to return to in the body when we’re thrown off by life or react out of proportion, which happens often, whether we’re traumatized or not. We center through building awareness of muscles and breath and mood in a given moment, inviting people to notice how we habitually hold ourselves, feel or react and move, how that connects to the conditioned stories we tell ourselves about who we are. At the same time, we encourage them to imagine and slowly feel their concrete embodiment of seemingly abstract concepts like a sense of dignity in their bodily length, a capacity for connection in their physical width and time, pace or wisdom in their depth. They acknowledge their mood and connect to their purpose or what they care about or long to embody. When repeated as a practice, this provides an internal structure for a body to come back to and slows down reactions over time. It’s a way of getting people’s actions to be more congruent with their values. The elements and principles of centering also extend to other practices in pragmatic social skills like centered boundaries, requests, and offers or centering in transition or coordination, for example.

These practices and others that a practitioner guides a client in don’t really stand as isolated ones but build on one another as part of the arc of transformation, which can almost be like a plan or a program for a person seeking somatic healing to embody what they long to. We keep training and re-training bodies that the discomfort of feeling more is not necessarily dangerous and that it gets us feeling more of what we really want out of ourselves.

Somatics is relational in its healing. Most people want to trust more, to cherish their own worth, to love better, to be more loved, to be more at ease and worry less, to imagine more for themselves and society. Most have to feel more in order to do that. Some feel too much and in that case long to regulate their emotions more. Feeling can be scary or at least that’s what we’ve been told, or have experienced through violation or violence, and often believe. Traumatic symptoms can make feeling terrifying and unwieldy. So there’s all of that to contend with.

On top of that, you really don’t have to do any of this as a human—you do not have to delve into feelings. Many of us live our whole lives that way, feel safer that way. It’s a choice. It all depends on how much of yourself you want more of and that you want others to engage with more meaningfully. Hence the practice to gently build a home base in the body, to retrain some of those psycho-biological pathways, to gradually shrink our little smoke alarm amygdalas or warning signals in the brain so we can have access to more of who we are and our purpose, even under pressures and extreme duress.

Then there’s bodywork, the crux of somatic opening work, which involves a practitioner working with the connective tissues of a client, softening up any historical protectiveness and armoring, allowing for more release and possibility in the tissues. It’s not massage but happens with the practitioner applying contact while a client is lying down. It can involve breath patterns and conversation as well. There’s active collaboration between practitioner and client while the body is in what we call a more limbic state, more emotionally open. People can have a lot of emotional and physical sensation and memory rise up during bodywork. It opens the body up to more of itself. As Staci says, it’s about working through the body, not on the body. Staci is coming out with a book soon about all of her wisdom on this and the wisdom of many others doing this work. It’s going to be phenomenal. All of us in the field, especially those who have experienced her teaching in courses, are really excited about it.

Overall, somatic practitioner training and development involves a particular development of perception that is part cognitive, aware of interpersonal and structural power dynamics, and very intuitive and sensory. It’s also about getting yourself out the way so you can tune in to bodies and assess the emotional life happening under the skin. It involves training this intuitive listening just as much if not more than one’s cognitive understanding and also cultivating one’s own healing and embodiment as a practitioner.

I regard myself as a student in a very young, syncretic field that has to maintain humility and humor and experiment rigorously in order to do justice to people who seek out emotional healing. I also try to study a range of psychological and philosophical traditions alongside political theory. You’ve been to my office—you know I like to read. I think those of us interested in the lineages and innovations of somatics at this moment in history or in how we galvanize humanity towards becoming a better species-being, as Marx would say, need to stay smart and rigorous and funny and loving all at once to become a collective body that’s a healing force to be reckoned with. I personally like to practice a balance of irreverence and irony with sincerity and principle. It’s solid goth punk witch stuff. I engage wonder and compassion as best as I can with no gurus or silver bullets.