Happiness

Playing the Game; Do You Care If You Win Or Lose?

Happiness is linked to the values of love and family, not money and status.

Posted May 13, 2018

If you were asked to look inside yourself and honestly say what you cherished most in your life, what would it be? Making lots of money, rising to the top of your career, getting top in your college courses, making the top sports team, buying the latest iPhone, the biggest and best house, the most expensive fashion item so you could impress your friends?

Or would you say being loved and loving others, spending quality time with friends and family, simply being in a beautiful environment, having fun with your dog, creating an artwork or writing a story because it gives you joy and takes you away from the stresses of everyday life, running along a beach for the pure pleasure of feeling your body moving and the wind in your face, getting lost in a moving book or movie, dancing (as if no-one was watching!), preparing or eating delicious food with people whose company you enjoy, having the chance to help someone who needs help, doing voluntary work, meditating, listening to music or making music, spiritual experiences, new experiences, working in the garden, walking in the hills, playing in the snow, helping save a plant, an animal, a coral reef from extinction, seeing a new mother or father with their first baby, remembering how your first sight of each of your own babies felt, celebrating feeling and being healthy, being happy.

My guess is that 90% or more of you will find that these last values are way higher up your list of what is deeply important to you than those values listed in paragraph one.

And this is what the research shows as well. Professor Niki Harré, a New Zealand community pychologist, has for many years being carrying out research and leading workshops on the values that are important to us and that not only make us happier but make the world a better place for everyone. This week she published a new book called ‘The Infinite Game: How to live well together’ that explains her thinking, her influences, her research results, and provides practical suggestions and guides on how each of us can enrich our lives, the lives of others, and our world. It is a book that is thought provoking, clearly written and will engage anyone who is interested in being happier.

At an earlier stage of her research, Niki shared with me two Word Clouds that she and her colleagues had compiled from the responses of 1000 or more people from all walks of life. The first Word Cloud, reproduced above, is the sum of the responses of workshop participants when they asked to list three infinite values; things that could be defined as ‘Sacred, precious or special; of value for their own sake. They make the world truly alive. Things of infinite value can be of any dimension: an emotion, a relationship, part of the natural world, a quality or an object. In Word Clouds, a bigger font indicates more people listed that word. Few if any of you will be surprised to see that LOVE is the value listed by the most people, followed by FAMILY. The reason you will not be surprised is because you too would likely have listed those values or some of the others close in size to these two words. When I look at this word cloud I realise that the books I most cherish and the movies that make me happiest (whether it is laughing or crying or both) embrace many of these values.

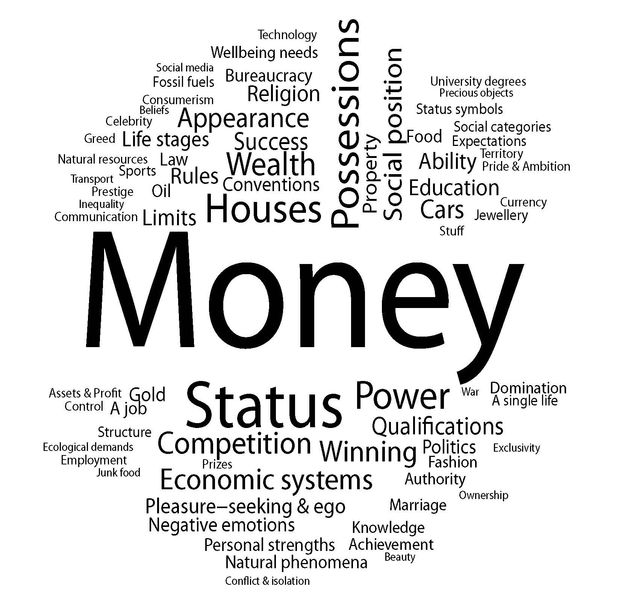

The other Word Cloud is a compilation of the three things these same people listed that in their opinion had the most finite value (not necessarily to them personally, but to society as a whole). Finite values were defined as those things that have worth because of what they signify or enable. They may be of value only to a particular group if people who deem them so. They can be in any dimension: an emotion, a relationship, part of the natural world, a quality or an object. And the finite value most listed was MONEY, with STATUS in second place. (Both Word Clouds were originally published under a Creative Commons License and are free to use for non-commercial purposes with attribution.)

Niki believes that we play two games as we journey through our days and lives; infinite games and finite games. As a metaphor for these life games she uses a sport; the playing of cricket—formal cricket and beach cricket. For those of you who live in countries where cricket isn’t much played, any game played in the Olympics or in a World Series that families and friends also play when on holiday will serve the same purpose! The formal game of cricket is strictly rule bound, and only those invited to play because they are good at playing are on the team. Beach cricket is open to anyone; the more the merrier, and rules be damned. Players can come and go as they please and no-one minds. There is so much laughing that sometimes the game becomes more of a party than a game. At the end it may be impossible to know who really won because players can change sides whenever they like. Those games are what we remember with a smile when we think about our holidays once back at work.

So how can we live our lives more happily most of the time and not just when we’re ‘relaxing,’ given that these infinite and finite values are so tied to our ways of being? Niki conceptualizes our living ‘strategies’ as games, just like the formal and fun ways we can play cricket: one game based on infinite values and the other on finite values. Guided by the 1980s research and writings of James P Carse, a philosopher who first suggested that we play these games, Niki and her colleagues have modified and further developed fifteen statements that describe where these two games differ. For example, the first pair of statements says the purpose of the infinite game is to continue the play, whereas the purpose of the finite game is to win.

In Niki’s book she takes each pair of statements and explains what these mean in real life and how we can change the balance in our own lives. Why? Because the infinite game is fun and makes us and the other players happy, whereas the finite game is restrictive and while often useful and necessary (eg: the game of training doctors is finite and useful) does not have to dominate our lives. Most of us, even if we choose to concentrate on playing finite games, and perhaps even encourage our children to join in by competing with their peers because of the silver cup and status and power it gives them (and us), are unlikely to experience long-term happiness by playing these games. If they encouraged their kids to play because of the fun and pleasure it gave them (and us), even to the extent that they were challenging themselves (and not so concerned about rating thenselves against others) then happiness would surely follow. Balance between necessary finite games and all-inclusive and open-ended infinite games is important of course, but discovering and understanding why you want to play a finite game may give you ideas about other ways you can embrace the values you cherish without playing to win. Money, goes the cliché, does not necessarily make happiness. Fame certainly doesn’t, going by the young entertainers who die tragically and alone. And then there is the saying that no-one ever said on their death bed that they wished they’d spent more time at work! Clichés often contain a large dollop of truth.

This is a very simplistic introduction to Niki’s research and its application to communities and the individuals that make those communities rich, but if you are intrigued, and if you can access it from yor location, do listen to this NZ Radio interview with Niki, or read her book.

References

Harré, Niki. (2018). The Infinite Game: How to live well together. Auckland, NZ: Auckland University Press