Relationships

Why Do Many of Us Love Quiet Novels?

In spite of the rhetoric that to be commercial a novel should surprise and shock

Posted April 22, 2018

Lately I have been thinking about quiet. Quiet time thinking and dreaming, quiet time reading, quiet time writing, quiet time when I wake in those hours before dawn when sleep is still craved but the mind has other ideas.

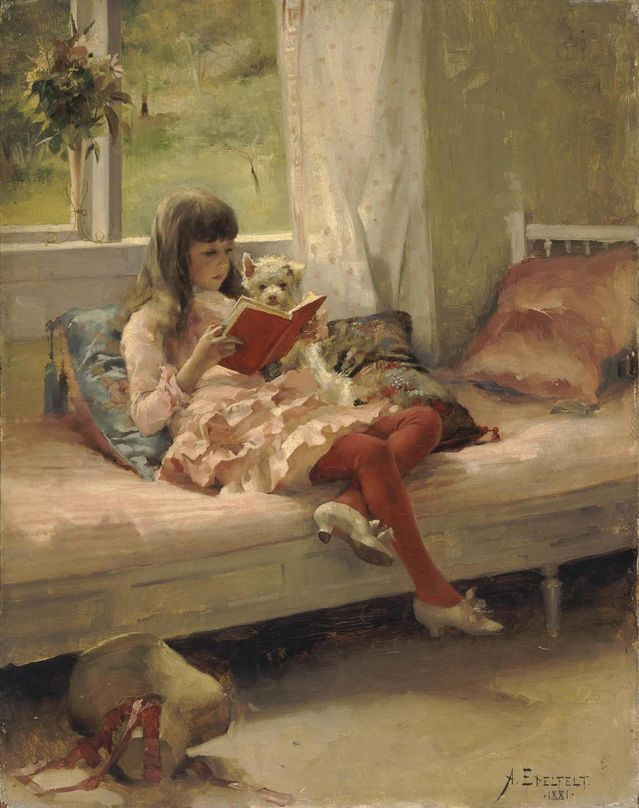

I am luckier than most in that I live on an off-grid island near a spectacularly beautiful beach which more often than not I can have to myself. I have always loved being alone, ever since I was a child and was bedridden every winter for a number of years. A ‘sickly’ child I suppose, although I don’t recall feeling sickly very often. I had plenty to occupy my mind while my legs lay still beneath the covers. My mother and I would listen to the fifteen minute soaps on the radio mid-morning—along with a cup of tea and a home-baked goodie—while we waited for the doctor’s daily visit. My father would bring me eighteen books every week, collected by the local librarian to keep me content. Then I had my imagination with at least two serialized stories to choose from in which I was the protagonist. It is only now, thinking back, that I realise that my stories were set in wild, quiet or crazy places where my body was always moving and my main companions included a German Shepherd, a horse, an elephant and a parrot. In one, single handed I ran an enormous back country station where I could be snowed in for the entire winter, and rode across raging rivers to save stranded sheep. My parents were absent, and I don’t think I dwelt on this too much. Perhaps they needed to work elsewhere; perhaps they had died in tragic circumstances. My other story that lay waiting for new chapters to appear, usually when my reading light was out and the rest of the household and world were asleep, was my life in a circus. I had the same suite of animals in this story, but at least there were also a few eccentric humans; lion tamers and the like. It was a roving life, the circus life. A life where the excitement was in the daily living; taking down the circus tent and putting it up again, playing with lion cubs!

Yet I am not an introvert, and most people who know me would say that I am almost the opposite. Loving to be alone, needed quiet, is not about being an introvert. I think we all need quiet some of the time. Perhaps for some it would be a quiet time with others rather than being alone, but I believe it is a human need. In today’s crazy world quiet is hard to find, but find it you must. And for me, one way to do this is to read quiet books. Anyone can read quiet books occasionally. It is not always necessary for a book to shock or startle, to rack up tension on every page. My debut novel (forget the previous ones that still sit in the drawer) has recently taken off up the charts again, two years out from its publication ( a slow burn I guess) and the reviews tumbling in from readers comment on its gentleness, its quietness, how it brought them to tears, how the small community of people on the remote tropical island where it is set remain in their minds long after they close the book (or turn off their Kindle!) This warms my heart because I am acutely aware of the rhetoric around what makes a successful commercial novel. Don’t wander from the main story, tension on every page, get that inciting incident in early because if you don’t most readers will give up before they get to the end of the first chapter. I agree that suspense is important, even essential, in good stories, but suspense can be quiet and even peaceful. All it needs is a question in the reader’s mind; how is this going to get resolved? Quiet books can and often do have loud emotions, big questions, be set in terrible situations—war zones, refuge camps, a blizzard, a psychiatric hospital, a cancer ward, a dysfunctional family—and have periods of dramatic action, but they are woven through with comtemplation and evocative descriptions of place and thoughts and connection.

At a 2017 UK literary festival Lisa Milton, the head of a large publishing imprint, commented that in her opinion empathy and kindness was the fiction theme set to explode over the next year. (Even empathy and kindness ‘explode’ in the commercial world of publishing.) Quiet books are often labeled as ‘literary fiction’ but they can be in many genres. Even full-throated thrillers can have quiet passages, and surely should do so as every reader needs a chance to catch their breath and go and make another cup of coffee. But the sort of quiet books I am talking about are those stories that gently meander along, taking time to savour the small, quiet moments of simply living, the often small cast of characters in the story taking their time to get to know the others in their lives and to learn more about themselves. This is how the reader becomes involved in their most intimate moments and discovers, quietly, not only about the characters in the book but about themselves. When a reader is immersed in a quiet book, smiles, chuckles, and almost always at some point of the book, tears, are normal responses. Quiet books are the ones you want to read again, perhaps years later. And every time you read it, you will find more to think about, more connections with your own experiences, and your throat will ache afresh.

So this is a plea to you to look for some quiet novels to read. Do it for your health, both mental and physical. Do it for your pleasure. There are many out there, but often they are not the big-name best-sellers, the commercial successes. You will find many published by small independent presses, and self-published. Thankfully there is however, a library of wonderful and well-known authors who have the skill and courage to write quiet books. Some of my most loved ones are ‘One True Thing’ by Anna Quindlen, ‘Lots of Candles, Plenty of Cake,’ a memoir and also by Anna Quindlen, ‘Crossing to Safety’ by Wallace Stegner, ‘Stoner’ by John Williams, ‘The Poisonwood Bible’ by Barbara Kingsolver, and ‘Salvage the Bones’ by Jesmyn Ward. Each of these books is stunningly different from all the others, in story, location, and cast of characters. Wallace Stegner and John Williams died many years ago but their novels are as current now as they were then. It is not the plot or the time during which it was set that makes a story current, but the way it can connect with our contemporary lives and our ancient souls.