Ethics and Morality

Writing the Truth With Empathy and Ethics

What more can we learn from ‘The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks’?

Posted November 26, 2016

“One of the most graceful and moving nonfiction books I’ve read in a very long time…A thorny and provocative book about cancer, racism, scientific ethics and crippling poverty, 'The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks’ also floods over you like a narrative dam break, as if someone had managed to distill and purify the more addictive qualities of ‘Erin Brockovich,’ ‘Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil’ and ‘The Andromeda Strain.’ …Skloot writes with particular sensitivity and grace about the history of race and medicine in America… “It has brains and pacing and nerve and heart, and it is uncommonly endearing. You might put it down only to wipe off the sweat.”

So reads the blurb on the book jacket of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot, first published in 2010. That blurb was extracted from the New York Times book review by Dwight Garner, and if you want to read the sort of review most writers could only dream about, you can read the complete review here.

Last month, I was excited to have the opportunity to hear Rebecca Skloot speaking and attend a half-day workshop taught by her at an author’s retreat hosted by the publisher of my own fiction, She Writes Press. (Such a retreat is likely a first for publishers, who usually do not put their resources into bringing their authors together to learn from each other and from publishing experts).

I had read Rebecca’s book back in 2010 when it first came out, but read it again in preparation for her workshop on story structure. Her dinner talk and her workshop where she used her own book as well as other stories to illustrate the complexities of book structures, multiplied my appreciation of her book and positioned it squarely amongst the very best books that bring to life the humans behind science in a way that is accessible to the general reader.

In my recent Psychology Today posts in this series on books that hover along the blurry boundary between fact and fiction, I have covered historical fiction based on real figures: many are excellent, as in the case of Behave by Andromeda Romano-Lax, (see post ‘Behave! Fictional biographies of famous scientists can educate as well as entertain’), but some are faulty, as in the case of The Other Einstein: A Novel by Marie Benedict (see post ‘The Thin Line Between Fiction and Fact: When is it OK in a novel about famous people to make stuff up?’). In this latter book, the author included invented stories that perhaps added to the book’s commercial appeal but denigrated the historical figure (Einstein).

At the factual end of the continuum from fiction to fact are narrative non-fiction books about people involved in scientific discovery and the scientific discoveries themselves. In this genre it is the author’s opinions and interpretations of the facts that make the content more or less factual and informative. A fine example of such a book is Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life of the Amnesic Patient, H. M. by Suzanne Corkin, published in 2013. This book, whilst accessible to the general reader, is not only the story of the most famous case in medical and psychological science, it is also the story of the research laboratory that studied him. Corkin is the MIT neuroscientist who headed that laboratory, and her book could be described as an autobiography of a laboratory and its scientists and research participants. It is thus is by definition factual, or as factual as any autobiography can be.

In that same Psychology Today post (see post ‘A Tale of Science, Ethics, Intrigue, and Human Flaws. Another look at the New York Times portrayal of a new book about amnesiac HM’) I compared Corkin’s book with another book, Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets by Luke Dittrich, featuring the same patient and neuroscientists, but written by a journalist. His method was to research the facts behind the book, and one of his motivations for writing the book was that he was the grandson of the neurosurgeon involved in the story. Dittrich claimed that his book was based on research, that it was factual. Indeed it is both a good read and informative and factual about the often dark history of medicine, psychiatry, and neuroscience. But Dittrich also allowed his own perceptions and interpretations and imagination to suggest to the naïve reader that some of the people and institutions involved acted unethically when the true facts did not support this.

I have also written about the potential ethical issues facing authors who write novels in which the main characters, while clearly fictional, are to some degree based on well-known people. In The Man Without a Shadow by Joyce Carol Oates, the same patient, HM, is used as her basis for her main character, and she also draws on Corkin’s book when writing about the fictional laboratory in her novel. The issue here is that some naïve readers may not realize that the real characters and laboratory procedures that informed aspects of the novel were not unethical like the fictional characters and laboratory! (See post ‘Can Novels Influence Our Beliefs About Reality? A novel loosely based on amnesiac HM portrays women scientists as unethical’.)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is in the same genre as Dittrich’s book. Of course it was written six years before Dittrich’s book was published, and it appears to me that Dittrich modeled his book rather closely on Skloot’s book. There is nothing wrong with that, and indeed it is a smart move given that Skloot’s book has been on the best seller lists ever since it was first published, has won numerous prestigious awards, and has over 26,000 text reviews and 355,000 ratings on Goodreads with an average rating of greater than 4 out of 5. But Skloot’s work is a hard act to follow, and having heard her speak about her process in writing it, the reason for her book’s success—and which few other books, including Dittrich’s recent book have not equaled—becomes clearer.

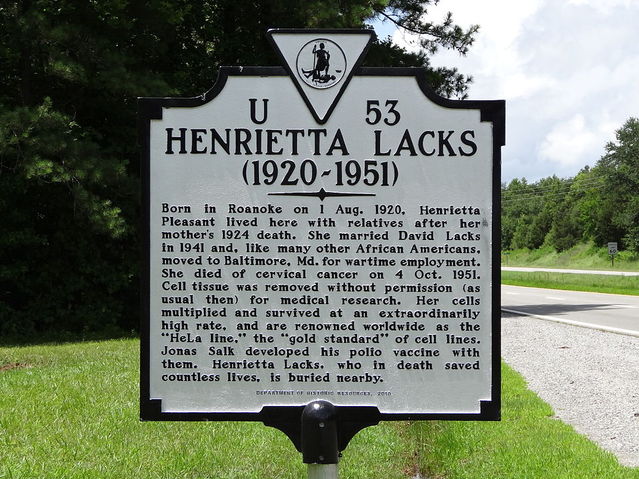

The basic story goes like this: In the 1950s, Henrietta Lacks, a poor Southern tobacco farmer from Virginia, was diagnosed with a very virulent form of cervical cancer. She was treated unsuccessfully at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where samples of her cancerous cells were taken as part of her treatment and indeed for research purposes as was common in a research hospital. These cells were cultured without Henrietta’s knowledge or permission (also as was common in the 1950s), and to the excitement of the medical scientists her cells—unlike all the other samples from patients and various cancers they had attempted to keep viable in test tubes—continued to divide indefinitely, in contrast with normal human cells which divide about 40 to 50 times before dying. Henrietta’s cells thus became the first immortal cell line cultured by scientists. They were named HeLa cells (the first two letters of Henrietta’s first and last names, a standard means of protecting the donor’s identity in the same way that being known only by his initials ‘HM’ protected the amnesiac patient while he was alive). They were used for medical experimentation and made available throughout the world to medical scientists for their research. They are still being used (and on the negative side have contaminated many other cell lines used for experimentation), and it is estimated that today all HeLa cells strung together could circle the earth 3 times, and they would weigh 50 million metric tons or the equivalent of 100 Empire State Buildings. HeLa cells were vital for developing the polio vaccine and have added immeasurably to our knowledge of cancers, viruses, and the atom bomb’s effects and have been a factor in important advances in cloning, gene mapping and in vitro fertilization. Since the 1950s they have been bought and sold by the billions.

The story of the HeLa cells is one of the three main stories in Skloot’s book. The under belly of this spectacular tale of science is that Henrietta Lacks and her family and living descendants knew nothing of the importance of the HeLa cells until journalists sought them out, and they benefited not one iota from the use of those cells. Henrietta was buried in an unmarked grave and her family lived in poverty and had no health insurance when Skloot contacted them to ask if she could tell their story.

Hearing Skloot talk about the ten years of research and writing and revision that went into this book and her creative and innovative methods of bringing the book to the attention of reviewers and readers, provided a window into why this book has been so acclaimed and so successful. Skloot first became intrigued with the topic as a schoolgirl when she learned that the woman who unknowingly donated the most important cells in medical science was a poor young black mother who died soon after her cancer was diagnosed. The research Skloot went on to do took over her own life, and became her passion. The second major story in her book is that of Henrietta and her family, their lives as poor blacks, and their exploitation in the name of science. This, of course, highlights a much wider story about these discomforting issues in the US and many other countries in the recent past. In her mission to understand the story from the Lacks’ family perspective, Skloot gradually and with enormous effort, persistence and empathy became a trusted friend of most of Henrietta’s family, and especially of Deborah, her daughter. As Skloot later wrestled with the complex structure of her book, the story of her own developing relationship with the Lacks family and with Deborah in particular became another story strand. The final book comprises three elegantly interwoven stories; the story of the Lacks family, from Henrietta—dead long before Skloot knew of her existence—and her living descendants; the scientific story of the HeLa cells and the scientists and institutions who made medical breakthroughs because of them; and the story of the journey of Skloot’s research and her developing connection with the Lacks family.

That is the power of the book, and what gives it such universal appeal. It is a story of science, of race, of discrimination, of ethics, of recent American history, of the writer’s research process, and of human relationships. It encourages the reader to consider the importance of bioethics and the control we have over our own body parts and their use, whether we are alive or dead. It allows us to contemplate the threats to our privacy that science poses, and our own feelings about the levels of privacy we wish for our own bodies. Some of us may believe that giving our bodies to science (with our consent!) when we no longer have need of them is a fine thing, and it may not concern us if our identity is known via our DNA, for example. Others will hold intermediate or opposite views.

It is horrifying to note that in March 2013, three years after Skloot’s book was published, scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory sequenced the full genome of a HeLa cell line and published it online without first seeking or gaining consent from Henrietta’s family. The issue with this is that aspects about the genetic makeup of Henrietta’s living descendants could be inferred from the HeLa genome. The European team apologized and took their HeLa genome data off-line after hearing from the Lacks family (who were now confidently able to stand up for their rights as a result of Skloot’s book and her championing of their cause). This demonstrates how difficult it is to get ethical messages heard even by today’s scientific communities, let alone the general public, even when those issues are clearly illustrated and much publicized by a best selling book like Skloot’s.

In the ten years since Skloot’s book was published, as far as I can ascertain there have been no proven claims that it is in any way factually inaccurate. This is a remarkable achievement and compliment to Skloot’s painstaking and careful research and writing. It is probably the most significant reason why her book stands head and shoulders above Dittrich’s book, which was criticized as factually inaccurate and unethical in its inferences about some of the scientists and institutions it portrayed. An article in STAT, the news site of Scientific American, discusses both the science community’s critiques as stated by MIT and also conveyed in a letter to the New York Times signed by more than 200 highly respected scientists from around the world, and Dittrich’s responses to those critiques.

Dittrich’s downfall was that he was unable to connect in a genuine way with those scientists and institutions he wrote about when he was researching the book, and thus his writing became increasingly fictional. To be fair, Dittrich worked hard to try and make those in-depth connections, as did Skloot (who is also a journalist), but for reasons unknown, he was unable to convince them to trust him sufficiently to allow him to obtain an accurate and fact-based understanding of some of the people and science that made up part of his story. In contrast, his stories about his grandfather, the neurosurgeon whose ethics were very suspect even in the 1950s when he was performing more lobotomies than any other surgeon, were insightful and horrifying, allowing him to explore and describe the terrible treatments psychiatric patients were forced into during those years. To discover who his grandfather was and what drove him was Dittrich’s real passion, and his book would have been much finer if he had not attempted to widen the story and increase its commercial (and controversial) appeal by embellishing the other story, the one he did not research as carefully as he should have or could have; that of HM and the scientists who studied his amnesia.

The moral of this tale of books that tell page-turning stories that are factual but have wide general readership appeal, is perhaps that the authors must be passionate about the people and stories they are writing about, persistent in their research and journey to discover the facts—as well as attempting to understand the personalities involved— and dedicated to telling their story accurately as well as beautifully, without bowing to controversy for the sake of making the book more commercial. There will be few who achieve this daunting task, but let us hope many will try and some will succeed, as books like these are treasures.

Please subscribe to my monthly e-newsletter!