Social Learning Theory

Is Your New Habit Not Sticking?

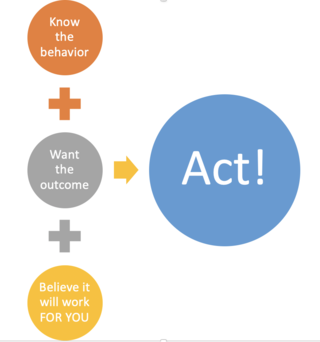

Bandura's social efficacy theory identifies three components to action.

Posted January 13, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Physics has gravity (it's not just a good idea, it's the law).

Psychology has learning theory. The basic ideas behind learning theory are deceptively simple:

- If you are rewarded for something you will do it more often.

- If you are punished for something, you will do it less often.

- If something bad is happening and it stops, you'll repeat whatever stopped it.

- If something good is happening and it stops, you'll be less likely to do that in the future.

B.F. Skinner's work on reward and punishment taught us a lot about both animal and human behavior. Learning theory is so well established, psychologists rarely study it anymore. We just use it. I use it when I train my dog. It's basic to parenting and management classes. It's foundational to special education.

Learning theory is easy to define, but difficult to apply effectively. (A true story illustrating this point is here.) It is also quite subtle. For example, it varies with age, with teens being relatively more sensitive to short-term rewards and less sensitive to punishment than older people are.

Social Learning Theory and Efficacy

Skinner worked mostly with animal models. Albert Bandura's social learning theory gave us even more insight into why we don't always behave in the way that Skinner would have predicted. Bandura worked specifically on people and how we learn from each other. Introducing cognition (thinking) to the basic ideas of reward and punishment is a critical component of learning theory, and marks the change from learning theory to social learning theory.

One of the important lessons of social learning theory is that we learn from watching others being rewarded and punished. If I see someone do something and succeed, I'm much more likely to try it myself. I learn from their reward vicariously. If I see them punished, I'm less likely to do it.

We are also most likely to learn from others like ourselves. For example, girls are more likely to emulate the behaviors of their mothers than fathers. The less like me the person I have knowledge of is, the less likely I am to learn from their experience.

Why do we do we what we do? Three components of action

When my students go into the classroom, they know how to act as both students and professors, but act as students. Why?

This is where the social efficacy part of Bandura's social learning theory comes in. He argues that several things have to happen for us to enact a behavior.

1. Want the outcome. Let's take biofeedback as an example. Research suggests that biofeedback and other forms of stress reduction can make it easier to cope with anxiety and can reduce anxiety over time. That desired goal increases the likelihood that you'll try biofeedback.

2. Know the behavior. Second, you need to know the behavior. If no one teaches you how to do it, you won't use it, even if you want to.

That's pretty basic. You're not going to do it if you don't want what it gets you or if you don't know how to do it.

The third component is more complex.

3. You need to believe it will work for you.

Let's unpack that.

3a. First, you need to believe that biofeedback is an effective stress reduction technique. Plus, you need to believe that stress reduction is helpful in reducing pain in general.

If you don't think stress reduces anxiety or if you don't think that biofeedback reduces stress, you aren't going to use biofeedback even if you've been taught how to use it.

Reading about how the amygdala reacts to stimuli, for example, might increase your belief that stress influences anxiety, even if that connection isn't immediately obvious. Knowing that, in turn, might increase your belief that stress reduction might be helpful to you. Further reading on biofeedback or studies of its efficacy might also increase your belief that biofeedback is an effective technique. Knowing people who have used it and found it helpful could also help.

Bottom line: You need to believe something will help in order to do it. If you don't think it will work, you won't

3b. Finally, you need to believe that biofeedback will work for you. If you believe that you're not the kind of person who meditates, or that biofeedback works for some kinds of anxiety, but not for yours, or if you think it's something that some people can do, but you just have no talent for, you're not going to try.

Why? Because although you believe it may work for others, you don't think it will work for you.

That's what efficacy means: believing something will work. Self-efficacy means believing it will work for you.

Stuck? Diagnosing the problem

If you're having trouble starting a new habit and keeping going, look to see where the problem might be.

Do you really want the goal? You've thought about exercising more or getting out of bed earlier. It's not happening.

Ask yourself:

- Is this really a goal you want? And, if so, do you want it more than the effort you think it will take to get it? (In other words, what's your cost-benefit analysis?)

- If yes keep reading. Identify your sticking point.

- If you want it, but think it's too 'expensive', evaluate. Is there any way to make it easier to reach all or part of your goal? In other words, can you make the reward worth the cost?

- If no, don't worry about it. Focus on the goals that are more achievable or will make you happier.

- Do you have the skills? A lot of times goals are complex and we don't know where to start. Or they can feel overwhelming because there are so many things you can do that you don't know where to start.

- Start somewhere. If there is one thing you think will help and you know how to do, start there.

- If you don't know how, learn. Want to try biofeedback and don't know how? Try YouTube. Skills are the easiest things to pick up.

- Do you believe it will work? Physical therapists have a problem. People are injured. PTs prescribe an exercise regime. It hurts (punishment) and it's boring (more punishment). PTs know from lots of research, that doing the exercises will help. The problem is that almost no one does the exercises.

Why? Clients don't believe it will help. It just seems stupid. It's too simple. And it's hard. And it's boring. So they don't do it.

If you know there's something you should be doing and you know how to do it and it's not getting done, ask yourself: Do I really believe it will work? And, if so, do you really believe it will work for you?

If not, you're probably not going to do it. You will have to ask yourself. Why? And what next?

All of this is hard. If something isn't working for you now, figure why. Do you really want it (more than it costs?) Do you know how to get there? Do you think you can do it?

Building habits require action that we can only do ourselves.