Fear

How Playing Baseball in Prison Can Help You Face Your Fears

Lessons from San Quentin on sport psychology

Posted March 5, 2015

Not many people like to socialize with some of the nation’s most notorious criminals. Even fewer challenge them to a competition, and I’d be hard pressed to find any of them whose teammate accidentally pelted one in the helmet with a baseball and lived to tell the tale. But that’s exactly what Chief Revenue Officer of Quarterly and self-described “baseball humanitarian” Aron Levinson did, when he cajoled some friends from his amateur baseball league to challenge the inmates of San Quentin State Prison.

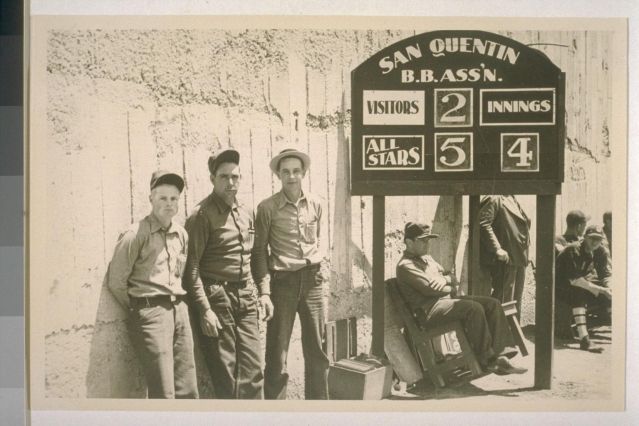

The San Quentin Giants, named after their major-league benefactors in San Francisco who donated jerseys to the prison, have been playing since the 1920s. The prison, California’s only male prison with death row, has been the home of California’s most infamous criminals since it was built in 1852.

Despite the prison’s reputation, the Giants are the oldest in the country and one of the very select few allowed to play baseball with outsiders. And they’ve got a winning record, too.

Levinson was a promising pitcher until he threw out his arm in Little League. 20 years later, he decided to go to the Los Angeles Dodgers adult fantasy baseball camp with his best friend, Juan, to celebrate their 30th birthdays. Since then, Levinson has remained steadfast with his resurrected passion, playing baseball in places like The Q and Cuba.

As a sport psychologist, I wanted to talk to Aron about one of the most critical factors in sport: Fear. It’s one thing to be afraid of your competitor’s talent, it’s another thing to fear for your life.

It’s a dynamic the volunteer coaches of the inmates understand. Eager to win, and get inside the heads of Levinson and his teammates, they were sure to let the visiting team know about San Quentin’s reputation and the grisly nature of many of its inmates’ crimes. It didn’t help that in the middle of the game the alarms went off—all the players were instructed to sit on the ground or risk getting shot.

Levinson, now a catcher, has a unique perspective on the game. He gets to see all the errors and missteps, and the fear mongering certainly worked. He could see it as his team played. And while Levinson’s case is a little extreme, athletes have to effectively deal with the same kind of fear every time they step on the field. Managing it is what separates the good athletes from the great athletes.

But it’s not just fear—of failing, of the other team—that hinders people. Levinson’s perspective is that it’s all about teaching yourself to overcome the fear of the unknown. Whether you’re playing baseball in San Quentin or working with at-risk youth in a dangerous neighborhood, fear keeps people away from new experiences that not only help others, but the volunteers themselves.

From a sport psychology perspective, the sort of emotional and physiological arousal that Levinson and his team faces when playing in San Quentin can be extremely detrimental, or beneficial, for athletes. Emotions like anxiety and fear can help get us “amped up” for the big performance, but can also make athletes crack when they’re overwhelmed by it. Levinson recounts a story in which a center fielder threw the ball to left field instead of 3rd base—that’s over-arousal at work.

In order to reduce arousal, many athletes employ techniques like breathing and other relaxation exercises that have been shown to reduce arousal and the fear response and thus significantly boost athletic performance.

Levinson’s story is certainly incredible. To play baseball in prison is truly an extraordinary challenge. But fear management isn’t just for athletes or athletes playing in prison. In our personal and professional lives, we all face cracking under pressure. It’s examples like Levinson’s that really show how sport psychology can positively impact our life, and not just athletic performance.

For more on sport psychology, follow Dr. Fader on Twitter and Facebook.

References