Relationships

Why Anxiously Attached People Can Be Avoidant, Too

How anxiously attached people who want love can also push people away.

Posted January 15, 2024 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- People with preoccupied attachment can have difficulty seeing the roles they play when experiencing rejection.

- Everyone has a degree to which they engage in avoidance—even those with preoccupied attachment styles.

- You can learn avoidant strategies to enact and ways to minimize your role in pushing people away.

One of the most difficult relationship conundrums to understand is: “If I want a relationship so badly, then how could it be that I am the one causing the rejection?” After all, if you want love and are open to people, and they are doing the same thing, then you should find a loving relationship. Right?

Well, there are quite a few ways that you can want love but behave in a way that leaves you being denied that which you desire. It might be obvious for people with high levels of avoidant attachment, because, by definition, they are avoidant of intimacy.

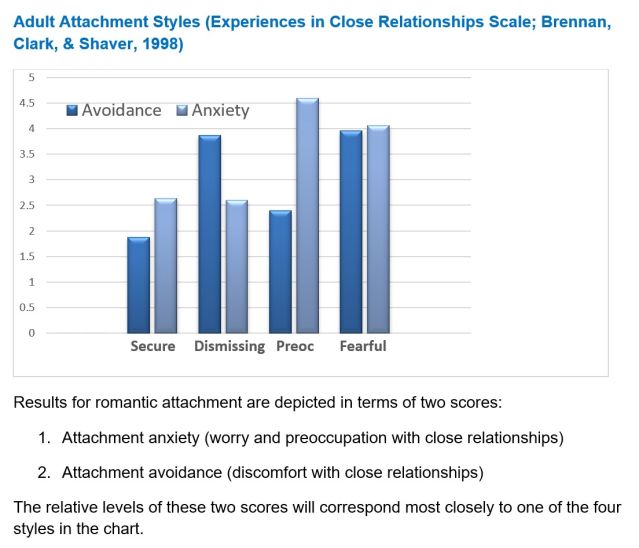

But, what about people with high levels of anxious/preoccupied attachment? They are characterized by moving toward close connection and intimacy. But the fact is that people with preoccupied attachment use avoidant strategies, too. The most frequently used measures to determine Attachment styles are all composed of various levels of attachment avoidance and anxiety. Take a look at the graph below, which is drawn from the averages for each style across multiple studies I have conducted.

Here are some anxious defensive behaviors:

- Being sarcastic and making pejorative comments. People with preoccupied styles can get activated by what seem like innocuous comments, or even when someone is talking about themselves and not showing interest or asking questions. The emotional activation that the preoccupied person feels might lead to an emotional hijacking and knee-jerk reaction that impels them to say something snarky (which can then strike the other person as “off” and lead them to back away).

- Going into stimulus overload and shutting down. Getting activated by something coming from the other person can lead to such a strong emotional activation that the preoccupied person literally shuts down (which is better than blowing up). In these cases, the preoccupied person might stop communicating and not say what they really think or feel.

- Over-elaborating and monopolizing conversations. Anxiety in an interpersonal interaction can make someone “flood the zone” by oversharing/explaining, telling stories, or sounding interesting. When they do this, they can come across as self-absorbed (which they are—preoccupied with their own emotional experiences). Looking self-centered and talking too much can make you look uninterested or not attuned to the other person and back them out of the interaction.

- Rejecting the other person before they can reject you. Nothing is more painful to a preoccupied person than being rejected by someone they are interested in. So, if they start picking up on cues in the relationship (which they might be misreading) that they might be dumped or otherwise rejected, they might reject the other person first as a preemptive defensive strategy. In the short run, this does avoid the feeling of rejection, but this assumes that they were going to get dumped themselves. This is sometimes a misread of the situation or an overreaction based on strong, painful emotions.

- Being easily insulted/reactionary and then becoming pouty or punishing. Being preoccupied means that your brain is always scanning the environment for signs of danger and rejection, and then having very strong emotional reactions when you find it (which you usually do). Being reactionary, making accusations, retaliating, or going off in an emotional outburst are all surefire ways to avoid intimacy with the other person and drive them away. You can’t punish people or “mad” them into loving you more.

You can, of course, add to this list from your own experience. The point is that when they get activated by signs/thoughts of rejection, which can be subtle, anxiously preoccupied people are likely to behave in a way that pushes the other person away. And, because they are absorbed by their own negative feelings (abandonment, anxiety, sadness, loneliness), they may not perceive their own role in these situations, but see only the other person’s rejection.

Here is what to do:

- Stop defending. You can’t prevent rejection by defending against it, so stop trying. (Defending is an “after-the-fact” reaction. This does not mean that you skip setting healthy boundaries to protect yourself.)

- Get a better sense of your timeframes and delay taking action. It is rare that a situation is so serious that you need to respond immediately. Take time (like a day) to let the strong emotions subside and see if you then think differently before taking action.

- Look for alternative explanations and try to understand the larger context. Maybe you found out that the person you have been dating for three weeks has been seeing someone else. You feel betrayed and rejected and make accusations—but what makes you think that you are not the “other woman/man/partner)” and that your dating partner is not looking for a better option (which is you)?

- Don’t make more of your emotions than they are worth (don’t take them so seriously). Emotions are data designed to inform you about a situation. But emotions are not truths in and of themselves. Just because you feel rejected does not mean that you are being rejected.

- Ask questions with a genuine air of curiosity. Show interest in understanding how the other person ticks even when they are making decisions or taking actions you don’t like. If you understood what underlay their choices, their behaviors might make a lot more sense and allow you not to push them away.

References

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.). Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46-76). New York: Guilford Press.