Bipolar disorder can carry a host of practical problems for both the person with the condition and those around him or her. But it can also bring with it interesting questions of identity.

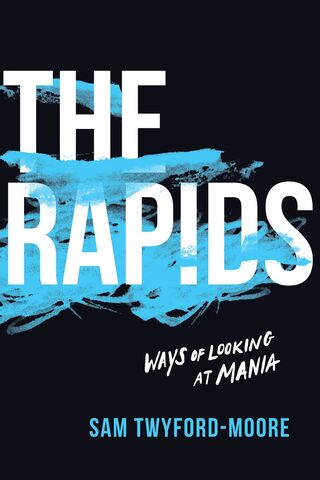

As you note, there is quite a cultural bookshelf on bipolarity. What prompted you to add to it with your book, The Rapids?

The Rapids came out of my own story, of course, but in telling it, I saw an opportunity to take a long view and to investigate how other people had lived their lives with the condition. There was about 100 years between my diagnosis and the term first coming into general use. So I wanted to look at how others had lived with and discussed the same illness—Spalding Gray, Carrie Fisher, Kanye West, and Delmore Schwartz all factor heavily in the telling of my own story.

What do you believe you are adding to it?

I would leave that up to the reader, ultimately—as I am sure any writer would—but I think you can be conscious of the fact that you are adding to an existing body of work, adding a single voice to the chorus, with the hope that that voice helps both strengthen and test what is being said.

What conversation do you hope to start with The Rapids?

I wrote The Rapids in a year that followed a very difficult mixed state episode—meaning I was living with rapid cycling between depression and mania on a daily basis—and so I was writing with that time close to mind. I was thinking a lot about how people had treated me during that period. Some had made that episode much worse, by not slowing down and seeing the illness behind some of my behaviours. I don’t think they were being malicious; I think it can be very confronting and confusing encountering someone in a manic episode. So I was hoping the book would ignite a conversation around visibility and caution.

If creativity is the least interesting aspect of bipolar disorder, what is the most interesting aspect?

I wouldn’t say that creativity is the least interesting aspect of bipolar disorder. I would, however, say the discussion about the connections between bipolar and creativity was exhausted, at least as a subject for me to write on—if only because it’s territory that’s well covered, primarily in Kay Redfield Jamison’s masterful Touched by Fire. To answer the original question, however, I think the most interesting thing about bipolar is how you hold on to a sense of self when you have a condition that distorts and twists the public image of yourself.

When is bipolarity a superpower and when is it a disability?

This duality comes from a lyric on Kanye West’s song "Yikes" from his short record Ye, which was released in 2018. I think the point should be that it is always both—that disability has core empowering aspects, always. The U.K. is, in many ways, the world leader when it comes to disability politics, and they adopt the social model of thinking about disability: I’m not the problem, what is in my way is. I carry around that model of thinking with me always.

One of the side effects of medication is making the illness invisible to yourself. How does that invisibility affect you? Or others?

It’s an interesting question. If you have an underlying lifelong chronic illness, I genuinely believe that illness has to form some part of your identity. So the question becomes, what happens when effective treatment of the illness, as such, makes it “go away”? Is it still there somewhere? Suppression isn’t the same as eradication. I would argue that the treatment and all the changes you need to make your own life are part of the overall condition—so, of course, it’s never really gone. Stability is hard-fought and hard-won and deserves its story to be told too. You can’t make that part of it invisible.

What is mania as a cultural identity?

The book is certainly a pointed attempt to look at what manic-depressive means as a cultural identity. If you live with a lifelong chronic illness, then I do think that factors as part of your cultural identity; I don’t think everyone needs to sign up to that, but I think it’s important in my life. It’s just a matter of saying I live with this, it has impacts on my life, and if you want to know me, you need to know that this informs my person.

Do you believe you have a psychiatric disability? Do others?

I can’t —and won’t—speak for others when it comes to these matters. But certainly, I personally see manic-depression as a psychiatric disability. If we take the meaning of disability as one that limits senses or activities, then that is certainly the case with both mania and depression. Indeed, Dr. Peter C Whybrow, a prominent psychiatrist, writes in his landmark book A Mood Apart that “Depression and mania are disabilities of the mind.”

Disorder, disease, illness, condition—language is important. What do you and don’t you like about each?

In writing a book you do need to find a lot of different ways to describe any single topic—otherwise you get a lot of clunky, repetitive language. So I used all of the above and, I think they all, more or less, fit the bill. Some were a better fit than others. I think illness might be the one to reclaim and rewire, at least when it comes to describing mania, as it can feel the opposite of illness—you feel in extreme health. So maybe illness is a little misleading, and there are few disabilities you would actively call “illnesses.” Still, it has its uses.

Do you think social media have made mania worse?

I do think social media can certainly amplify some of the worst aspects of mania — particularly its tendency to lead to isolation. If, during a manic episode, you are more likely to lash out and say things you would not otherwise, then that is going to be intensified if you can write and record those things online. I wish someone would have taken my phone and laptop away from me during certain episodes. I sent emails that I shouldn’t have. I tweeted some opinions that I wouldn’t have said aloud. There are people who were rightly upset by these instances, but I would hope they could see beyond those moments and understand what was going on in my life and that I wasn’t exactly in control.

What insights about yourself or about your condition/disease/disorder/illness did you get after completing the book?

That’s a good question. I think I’m in the best place I’ve ever been in terms of living with both mania and depression—not only because I haven’t had an episode since writing the book. It’s been three years since I was last hospitalised. I’m extremely proud of that. Not that there is ever any shame in relapse.

If you had to limit yourself to one item, what one idea or insight would you like readers to get from this book?

Take care of yourself and take care of others where you can.

About THE AUTHOR SPEAKS: Selected authors, in their own words, reveal the story behind the story. Authors are featured thanks to promotional placement by their publishing houses.

To purchase this book, visit: The Rapids