Codependency

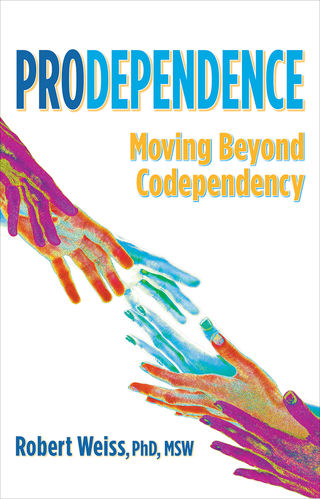

Prodependence: Moving Beyond Codependency

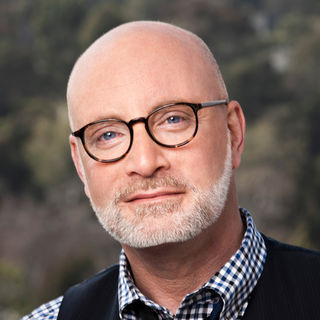

The Book Brigade talks to psychotherapist Robert Weiss.

Posted September 27, 2018

Substance abuse not only has a major impact on the health of the user but disrupts important family and social relationships. Just how much—if any—responsibility loved ones have for the problem has long been a highly controversial topic.

What is prodependence?

Prodependence is a new concept and paradigm in addiction healthcare. It is intended to be an improved method for viewing and providing treatment to spouses and other family members of substance abusers (and other troubled people). The prodependence model, using an attachment-sourced view of dependency, addresses many of the shortcomings of the 35-year old codependency model, which was based in trauma theory.

Codependence suggests that family members of substance abusers need to focus less on the abuser’s challenges and more on themselves. This is in part because their interactions with the abuser are defined (by codependency) as contributing to the addiction. This typically leaves loved ones of substance abusers feeling more confused, blamed, and misunderstood than supported, included, and validated.

Prodependence avoids negative labels like enmeshed and enabling, choosing instead to celebrate and validate a caregiving loved one’s willingness to remain connected with a family member of a substance abuser while teaching the caregiver how to survive and help heal active substance abuse.

The idea of codependency has always been controversial and rejected by science. What is your concern with it?

Intentional or not, codependency applies a pathological sheen to those who love and care for substance abusers. It is a negative label applied to a loving person in crisis, and I see that as unnecessary. More importantly, “codependent” is a label that is often resented and rejected by loved ones of substance abusers in their early healing. They don’t like feeling blamed for the user’s problem. (This was likely not the intention of the codependency movement’s progenitors. Nevertheless, that is where that model has landed.)

The codependence model is rooted in discussions of early-life trauma; it looks at how early-life trauma in the partner of a substance abuser is affecting his/her relationships. Unfortunately, for many loved ones of substance abuser’s (and plenty of therapists), framing a person’s commitment to helping a troubled loved one as stemming from that person’s reignited early-life trauma feels blaming and shameful. It feels as if the caregiving loved one is being pejoratively labeled for “loving too much,” or “loving selfishly,” or “trying to control the substance abuser.”

Why is it a mistake to think of addiction as a disease?

I believe that when applied to substance users, the disease model is not a mistake. When it’s applied to families of users, I’m less enthusiastic. Certainly loved ones act out in relation to the ongoing difficulty of living with an substance abuser, so we could say there is a “family disease” of addiction. But applying systems theory to the disease model of addiction, as so many people do, does not work for me because this has come to mean that everyone in the family—especially the spouse—is in some way contributing to the addiction. I see family members as reacting and responding to the trauma of living with an active substance abuser and their fear of losing a meaningful attachment.

All family members are deeply affected by an addiction, just as all family members are deeply affected by cancer. But codependency implies (while prodependence does not) that the addiction is in some way the fault of the non-addicted family member(s).

Substance abusers use because they want to use. No family member is ever responsible for that.

Why do you think we as a culture are struggling so much with addiction right now?

Unlike the sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll culture of the late 20th century, which contributed to so many problems of substance abuse, online experiences are leading to addiction and related behavioral disorders. Digital media, with its affordable, anonymous, often instantaneous access to pleasurable experiences like gambling, gaming, sex, and spending, is, without question, driving the new behavioral addictions of the 21st century.

What do you mean when you say addiction is an intimacy disorder?

Addictive substances and behaviors are used to self-medicate and self-regulate unwelcome and uncomfortable emotional states. Healthy people turn to other people. Substance abusers, however, tend to cope with stress, depression, anxiety, loneliness, boredom, attachment deficits, and, most of all, unresolved trauma by turning to addictive substances or behaviors. They do this because, for them, unresolved childhood trauma (often preverbal) has poisoned the well of attachment. They fear and feel insecure with emotional dependency and intimacy; thus, they turn inward and isolate, using drugs or behavior to dissociate rather than relying on the support and love of those who might nurture them. For these reasons, I (and many others) conceptualize addiction as an intimacy disorder—people replace healthy human dependency with dependency on addictive substances and behaviors.

And what does that imply about helping those with substance-use problems?

Unquestionably, the most important people in a user’s support network are his or her closest loved ones. When he or she finally learns to trust that loved ones will be there in healthy and supportive ways, there is a secure base that he or she can turn to in the chaos. And that makes staying sober much easier.

The fear, of course, is that caregiving loved ones might (and sometimes do), as a way of keeping the relationship intact, behave in ways that perpetuate the addiction. Nevertheless, prodependence does not see detachment as the solution, with caregivers continuing to love the person but only from afar. With prodependence, the solution is to stay connected and to continue caregiving, but more effectively, with better self-care and boundaries.

Are there relationships that protect people from developing substance-use problems?

Without question, a child who experienced meaningful attachment to loving, supportive caregivers (parents) is far less vulnerable to addiction than someone who grew up with relational unpredictability and trauma as the norm.

Who is your audience for this book and why?

I have written this book for two primary audiences: 1) therapists, and 2) loved ones of those struggling with addiction. Codependence was first written about for and by therapists, but the concept quickly grew into a cultural phenomenon (for better and for worse). Unfortunately, while there have been many new models and paradigms created over the past 35 years related to the treatment of addiction, when it comes to loved ones of those struggling with addiction we have but one model—codependency.

I want people to understand that codependence is not the only way to think about those in relationship with a a substance abuser. I want to depathologize caregiving. I want readers to understand that causing loved ones to feel that they are in some way contributing to the addiction, as codependency does, is not useful in treatment. In fact, I as a concept it has done as much harm as good.

Thus, we are long overdue for a model driven more by attachment and love than judgment and pathology. We are long overdue for a paradigm that is more welcoming and positive, with an approach that celebrates and values a caregiving loved one’s willingness to support and stay connected with an addicted family member. That model is prodependence.

What is the single most important point you want readers to take away from this book?

You can never love too much! You can love ineffectively, you can love inadequately, you can love in less than helpful ways. But love too much? No way.

Essentially, I want readers to understand that even behaviors considered problematic, like enabling and rescuing, can be reframed as expressions of love (albeit misguided). As such, we should not blame, shame, or investigate the motivation of loving caregivers, because doing that alienates them. Why not just validate their love while redirecting it in more effective ways?

About THE AUTHOR SPEAKS: Selected authors, in their own words, reveal the story behind the story. Authors are featured thanks to promotional placement by their publishing houses.

To purchase this book, visit:

Prodependence: Moving Beyond Codependency