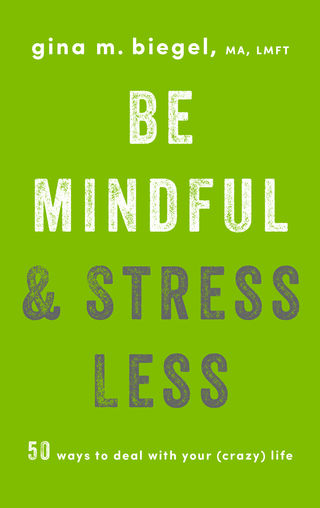

Mindfulness

Be Mindful and Stress Less

The Book Brigade talks to psychotherapist Gina Biegel.

Posted July 19, 2018

Stress is ever-present in our lives. We can’t change that. But we can change how we manage it. A great deal of evidence suggests that mindfulness confers stress-hardiness and allows us to approach challenging situations more directly, without adding to the difficulty.

There are lots of books about stress. What makes this one different?

What makes this book unique is its breadth. It is waist-high in solutions—50 of them to be exact. People talk a lot about problems—lamenting and ruminating about stress—but it is a different thing to get into action, to do something different, to get out of the poor-me attitude. This book offers readers a roadmap to kicking stress to the curb.

There are also many books about mindfulness. What makes this one different?

This book is what I consider “mindfulness plus,” the plus being positive neuroplasticity. Mindfulness is about paying attention, but it is also about deciding what to pay attention to. Do you attend to that stressful to-do list or keep that depressing song on repeat, or do you attend to things that nourish and support your mood? Do you engage in self-care, take in the good, surround yourself with people who foster your needs for safety, satisfaction, and connection? Leading-edge research shows that the brain responds to how you use it, to learning or experience. By choosing to attend to positive or pleasurable experiences (instead of our automatic tendency to tilt toward the negative), you can create neural connections that tilt toward the positive. I look to my mentor Rick Hanson, who reminds me that doing more that is good for you is better—mo bettah, as he puts it.

What does it mean to be mindful?

Mindfulness is about becoming more deeply aware of the moment as it is unfolding, to notice what is already here to be noticed—the experience of your senses, your thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations. Take, for example, when you are looking all over for your phone before you leave for work. Being mindful is knowing where your phone is to begin with or catching yourself while you are looking for it and noticing that you were so caught up with making your kids lunch that you forgot you had put it in your pocket. Mindfulness gives you the opportunity to be present to your life—even the painful moments. When you aren’t being mindful, you tend to be tuned out or on autopilot. Noticing when you have tuned out and tuning back in is being mindful because you have attended to that particular moment.

Is there something about mindfulness that most people do not understand?

I think that many people don’t understand that mindfulness is about being present to everything, not only the good or pleasant but also the ugly, embarrassing, and shameful. It is about walking through life witnessing what is without jumping on the train of thoughts or giving more energy to pain than you need to. Mindfulness isn’t about levitating, enlightenment, or being a blank slate—it is waking up to what is. It is a way of living, not a state of being you sit in for 20 minutes at a time.

What is the evidence that mindfulness is a good approach to stress?

Research that I have done with adolescents, and that many of my colleagues have done with adults, statistically points to mindfulness as a significant stress reducer. Beyond peer-reviewed journal articles, anecdotal evidence points to the efficacy of stress hardiness and improved perceptions and appraisals of challenging situations. I find that when people change their views of other people, places, things and situations, their stress can lessen. More often than not people can right-size stressful situations without adding to them. That isn’t to say people aren’t going to encounter stress in their lives; what changes is the way they manage it.

What makes it so good?

You aren’t a passive observer to your life as it is unfolding; instead, you are in the driver’s seat. You get to choose how present you want to be to your life. You have control; and for teens, who don’t have control over many areas of their lives, that can be very empowering.

What is the most challenging situation you ever faced that was helped by mindfulness skills?

I have been working to bring mindfulness to people, more specifically the adolescent population, for the past 15 years. I have seen boundless positive effects time and again for the large number of those I have worked with. I have seen many have significant Aha! moments arising from a simple sticker in my office that reads “Don’t believe everything you think.”

What is the relationship between mindfulness and mood?

Mindfulness and mood inform each other. When you are mindful, you are often more aware of your mood—your feelings and emotional state. When you are experiencing feelings, you can often (1) become more quickly aware of and tuned into them and (2) engage in mindfulness and positive neuroplasticity practices. Self-care and knowing what your needs and wants are and having them met can adjust a mood when the desire is for it to be changed.

Why is self-acceptance important to mindfulness?

Rather, is it that mindfulness and self-acceptance can converge? The aspect of mindfulness that I think coincides with self-acceptance is looking at things more objectively. Self-acceptance is about being with your gifts and flaws, or what I refer to as being perfectly imperfect. Similarly, when you are steeped in mindfulness practice, you tend to look at things objectively.

Have we become too reactive to our experiences?

We can be! Being reactive rather than responsive often happens when you aren’t noticing what you are doing as you are doing it. You might snap at your kid when he or she was just trying to ask you a question, or you hit send on a text that you immediately wish you hadn’t sent. To counteract reactivity, you can engage in micro-pausing, taking a mindful moment, putting pause on your remote of life, and then proceeding. We have so many opportunities every day to take a mindful pause, even if for a microsecond. We then can choose how we want to respond instead of reacting. We can bring awareness of such choice to the decisions we make and the actions we take.

Who is the target audience for this book, and why?

Although I am most known for my work with teenagers and those who work with them, this book is for the everyday person—someone working construction, a janitor, a stay-at-home parent—the person who wants to bring mindfulness into his or her life in concrete and easily accessible ways. My perspective is that not everyone wants to spend an hour a day practicing formal mindfulness; not that there is anything wrong with that, but it isn’t a requirement. There are myriad ways to bring mindfulness to everything you are already doing—informal practice. Such activities as walking your dog or riding on an elevator can be brought to the forefront when you are bringing mindful attention to what you are doing as you are doing it.

What is the single most important message you want readers to get?

Self-care, self-care, self-care! It is imperative that we treat ourselves as well as we treat our devices, our pets, and our best friends. I choose these three because most of us charge our phones and keep them in pretty good shape so that they work, give love to our pets, and give wise advice to our friends. If you can offer yourself charge—physical and emotional—love, and cogent advice, you are on the right path.

About THE AUTHOR SPEAKS: Selected authors, in their own words, reveal the story behind the story. Authors are featured thanks to promotional placement by their publishing houses.

To purchase this book, visit: