Coronavirus Disease 2019

How to Socialize During a Pandemic

On the continuing right to avoid infection.

Updated September 26, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- The pandemic has forced us to confront mass suffering, loss, and preventable death at an unimaginable scale.

- Post-vaccine stress—tied to socializing during a pandemic—is widespread.

- Low-cost mitigations reduce this stress but depend on practical implementation.

“Modern society has largely exiled death to the outskirts of existence,” wrote Jacqueline Rose in a late-2021 Guardian “Long Read” on the toll of mass suffering, loss, and death from the pandemic. “But Covid-19 has forced us all to confront it…What, then, is the psychic time we are living?”

Though vaccines and antivirals such as Paxlovid have significantly reduced deaths from COVID-19 in many parts of the world, the United States continues to report around 1,500 weekly, virus-related deaths—at least 78,000 preventable deaths annually—as the world closes in on year 4 of the pandemic. “When controlling for population size,” UCLA’s California Center for Population Research calculates, the annual number of excess deaths nationwide rose “84.9% between 2019 and 2021.”

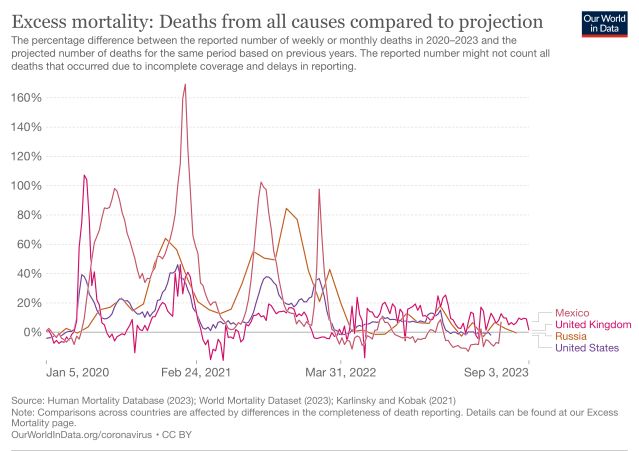

Nor is the United States alone in reporting figures far above comparable, pre-pandemic years. According to a coalition of health care insurers, “Excess mortality, defined as more deaths than normally expected, rose during the pandemic with estimates of 16.8 to 28.1 million worldwide excess deaths from all causes...As COVID-19-related deaths decreased through 2022, excess mortality continued to persist in many countries.”

“To be human, in modern western cultures at least, is to push the knowledge of death away for as long as we can,” Rose observes, but “if the pandemic has changed life forever, it might be because that inability to countenance death—which may seem to be the condition of daily sanity—has been revealed for the delusion it always was.”

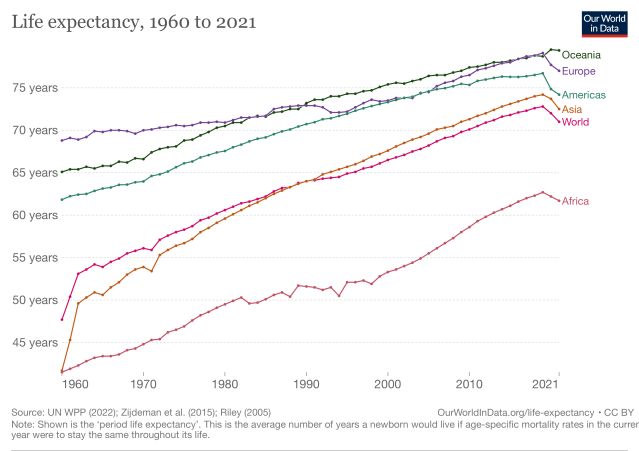

Since during pandemics we are unable to keep death at a safer distance—our standard preference, according to Rose, citing Freud—death keeps intruding, pressing for attention in newspapers and across social media. When combined with the documented sharp drop in life expectancy, post-2020, the numbers put in stark relief the implied value of our lives—one of several reasons the topic can become so volatile.

Examples of mass infection without sufficient mitigation and of government incompetence over routine public health measures help represent the crisis at a macro level (Sweden and the United Kingdom in 2020-2021), concerning a pathogen that since 2020 is known to be airborne and transmitted between people via infected aerosols. Social media, meanwhile, is full of more personal examples of shock at how indifferent others may be about COVID-19 welfare, even or especially when it affects the vulnerable.

One unforgettable example, relayed widely for the COVID-19 community over Med Twitter, outlined a brief exchange between two women who had been good friends for years. One asked her friend please to take greater care during their meetups out-of-doors, a continued source of pleasure to both, since for her younger children she had decided to mask during them. The offended friend replies, “Who do you imagine you are to remain uninfected, when everyone else has been sick with Covid multiple times?”

“Who do you imagine you are to remain uninfected?”

The exchange can teach us a lot about infection, risk, and the sadness of a friendship ending.

From the misplaced idea that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection is inescapable and unavoidable (false on both counts), the responder not only makes repeated infection seem routine and inconsequential, even for children (not by a stretch), but implies that mass infection is all her family and community deserves. In the process, mere steps to avoid infection are prejudged as arrogant. Even the wish to remain healthy is construed in the exchange as hostile to friendship because it is reckoned to be overestimating one’s importance—ultimately, the meaning and value we give our lives.

The psychic time in which we’re living

“What, then, is the psychic time we are living?” asks Rose, as many of us grapple with social incidents and exchanges close to those described above. (Disclosure: Rose chaired my Ph.D. in the 1990s.) Along with the daily risk assessments—stressful in themselves—over indoor gatherings that may include seminars and movie theaters, gyms and dance clubs, are calculations others are making about their safety, using criteria that may be altogether different from ours.

Even so, that shouldn't be insurmountable. Mitigations help us work out risk reductions in ways that enable us to socialize more safely, with a lower risk of infection, thereby reducing the risk of injury by infection to ourselves and others.

Part of the phenomenon of “lockdown divorces” involved partners who turned out to have insurmountable differences over COVID-19 safety. They help expose the larger stakes over life expectancy, longer-term health, and the need to lower the risk of infection. Once again, they put front and center how best to do so—with vaccines; indoor masking, which reduces inhalation of infected aerosols; eating and exercising outdoors; and low-cost HEPA filters that clean the air, removing airborne pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 that can cause long COVID and worsen health outcomes after repeated reinfections. Reinfections leave the immune system weaker, not stronger.

For all these reasons, postvaccine stress—tied to socializing while the pandemic is still ongoing—remains widespread and a thing. Declarations that “the pandemic is over” contribute to the stress. They imply that mitigations should end even as cases have started to rise countrywide—in some cases dramatically, as shown by wastewater data.

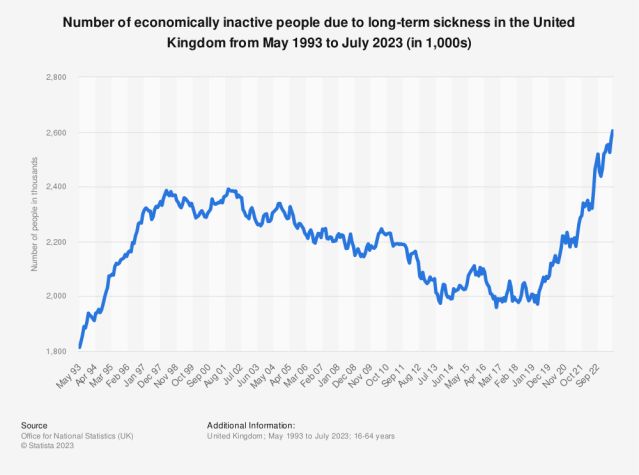

Advocates for a “return to normal” must ignore that increase and convince everyone that it doesn’t matter. Yet, after a well-documented lag, rising cases drive longer-term sickness and higher rates of disability from COVID-19, and help explain the significant numbers of physicians and nurses (one in five) falling sick from Long Covid. Meanwhile, hospitals and health care settings across the United States are not mitigating for the airborne pathogen. Earlier this year, their leaders pushed instead for an end to masking in health care settings.

Just as the pandemic has provided ample examples of disinformation at its most intransigent, it has also given rise to different ways of socializing, indoors and out, to accommodate a range of needs and varying levels of risk, accessibility, and disability. Across most of the country, gathering and teaching can be done successfully online. Masks remain an option when other forms of mitigation involving ventilation and air filtration are not available, or not yet in place.

The pandemic itself has forced us to adapt, to make socializing more flexible. The compromises extend to adjustments such as “lockdown relationships” and “lockdown marriages,” where extended proximity and an adjusted home/work balance have turned out to be sustainable.

For those, the negotiations and risk assessments weren’t insurmountable. They likely involved discussion of risk and harm reduction, including “negotiated safety,” a concept popularized in the 1990s to help control the spread of HIV. Then, as now, risks to personal safety combined with concerns about reduced life expectancy and weaker public health. Tied to the principle of harm reduction, negotiated safety aimed to extend life expectancy and strengthen public health, including through more resilient community ties.

Particularly because there is now a range of low-cost, low-effort, highly effective mitigations available to reduce exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in offices and schools, universities and hospitals, airports and bus stations, freedom from infection must remain a crucial goal.

First, do no harm—the oath that all doctors swear to uphold. Anything less would be an abdication of responsibility and public health—in the control of a serious, still-fatal infectious pathogen—when we can in fact mitigate it and reduce transmission. The crucial point is to reduce the inhalation of infected aerosols.

The issue is mostly one of implementation. We need a better plan to end this.

References

The C-MORE/PHOSP-COVID Collaborative Group. (Sept. 22, 2023). Multiorgan MRI findings after hospitalisation with COVID-19 in the UK (C-MORE): a prospective, multicentre, observational cohort study.” Lancet Respiratory Medicine Open Access [Link]

Leblanc NM, Mitchell JW, De Santis JP. (Jul. 2017). Negotiated safety—Components, context and use: An integrative literature review. J Adv Nurs 73(7):1583–1603. doi: 10.1111/jan.13228. [Link]

Rose, J. (Dec. 7, 2021) “Life after death: How the pandemic has transformed our psychic landscape.” The Guardian Long Reads. [Link]

Skipworth, W. Covid Drug Paxlovid Now Less Effective Than In Early Trials—But It’s Still Great At Preventing Death. Forbes. September 21, 2023.

Bailey, D. Insurance industry coalition forms non-profit to study baffling excess mortality. Insurance Newsnet. April 10, 2023.

Greenhalgh J, Simmons-Duffin S. Life expectancy in the U.S. continues to drop, driven by COVID-19. NPR. August 31, 2022.

Sibonney C. One in Five Doctors With Long COVID Can No Longer Work: Survey. Medscape. August 31, 2023.