SSRIs

How to Discontinue Antidepressants Safely: A Book Review

Several new studies address a widespread medical problem.

Posted December 20, 2021 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- One in six U.S. adults is currently prescribed psychiatric drugs at least once in a year, in 8 of 10 cases for long-term use.

- Studies repeatedly indicate that antidepressant withdrawal is a widespread, understudied medical condition.

- Recent books describe a history of drug makers and opinion-makers minimizing the problem as “mild” and “self-resolving.”

- How can patients end antidepressant treatment safely?

“There is currently no place,” writes Giovanni Fava in his recently published Discontinuing Antidepressant Medications (Oxford, 2021), “for providing competent healthcare to people who suffer from the consequences of antidepressant tapering and discontinuation.”

The roots of the problem are tied to medical thinking and assumptions, the book argues, with marketing also a major driver of prescribing rates.

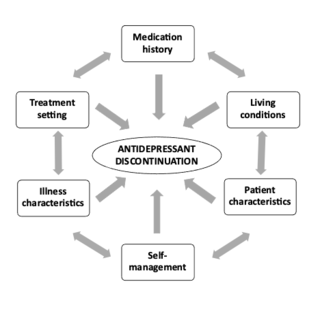

Starting medication is the easy part, Fava shows; ending it frequently much-more difficult. Yet prescribing for “unmet need” and “subthreshold” conditions has eclipsed an equal, medically necessary focus on deprescribing for treatment to end safely. Without that counterweight, large numbers of patients are effectively stranded, lacking the guidance, tools, and support to discontinue appropriately through slow and measured tapering.

With one in six U.S. adults currently prescribed psychiatric drugs at least once in a year, in 8 of 10 cases for long-term use, and comparable or higher ratios reported in the UK and across Europe, the matter of how to end antidepressant treatment safely remains of pressing concern for the tens of millions of patients affected worldwide. As Fava notes, “Dependence on, and an inability to stop taking antidepressants, represent a major, silent health emergency that has not received appropriate attention from national health services and research agencies throughout the world.”

As with Fava’s earlier writing—among the first to reckon seriously with antidepressant withdrawal in clinical settings—his unflinching focus on the condition ensures that his investigation carries weight and requires full consideration.

Fava is now Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Buffalo, New York. But in the early 1990s, he set up an Affective Disorders Program in northern Italy, bringing his psychopharmacological knowledge to bear on his clinical experience, and his patients’ difficulties in withdrawing from SSRI and SNRI antidepressants to bear on his therapeutic approach. The latter, he notes, soon collided with a psychiatric context in which both classes of antidepressants were championed as “solving” a problem of withdrawal besetting earlier, first-generation antidepressants such as the tricyclics. As Fava writes of a narrative that also first seduced him, SSRI antidepressants were seen as “powerful remedies” for the treatment of depression and anxiety, with “chronicity” in the drugs largely recast as “essentially a consequence of inadequate diagnosis and treatment.”

As we learn in the book, that overriding narrative—building on similarly misleading claims about the drugs correcting a “chemical imbalance” in a “broken brain”—was soon challenged by clinical experience.

“In the nineties,” he writes, “quite a different picture emerged with the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). We started being confronted with withdrawal syndromes that ensued with their tapering and discontinuation.”

The first of these was, in Fava’s case, a “wake-up call.” An adult male trying to taper his antidepressant treatment per instructions called to warn him, “I cannot make it another night this way.” The patient was frankly “terrified” of the adverse events he was suffering, among them “severe vertigo, gait instability, malaise, muscle aches, and visual hallucinations.”

“What is going on here?,” he asked of symptoms quite unlike those that had led him to seek help. Fava’s response is characteristic of his entire approach: “I felt we had the moral and intellectual obligation to provide an answer, no matter what the personal costs might be.”

The two-step sequencing program described in the book blends alert responsiveness to side effects with candid recognition of blind-spots in scientific knowledge. It dovetails with Fava asking himself such questions as “What was I missing?” and “What will be the long-term outcome of their disturbances?”

In the 1990s and 2000s, he explains, referencing multiple early responses to discontinuation problems (preferred terminology at the time), the pharmaceutical industry systematically “urged the downplaying of withdrawal manifestations upon discontinuation of SSRIs and SNRIs. The commercial plan was to expand the[ir] use ... from depression to other psychiatric disorders (particularly anxiety disturbances) and to prolong their administration to the longest possible time.”

As Fava notes, drug makers were “quite successful in minimizing these clinical events”—steps that in themselves “inflated” the drugs’ overall effectiveness from a “selective reporting of positive trials.” In scouring the literature for “medical help and competence” for his patients, Fava is “struck by the fact that the reviews that were available were characterized by a selective use of the literature, with a strong commercial bias (and indeed most of the authors had major financial conflicts of interest).” Among leading psychiatrists, the consensus at the time was that symptoms that did arise from discontinuation were “mild” and “self-correcting” after 1-2 weeks—language and timing it has since taken years to update and correct.

The theme of selective reporting and inflated results builds in the book, leading to some of its strongest statements: “By virtue of their financial power and close ties among themselves,” Fava writes,

members of special interest groups may systematically prevent dissemination of data which may be in conflict with their interests. Corporate powers have fused with academic medicine to create an unhealthy alliance that works against objective reporting of clinical research, that sets up meetings and symposia with the specific purpose of selling the participants to sponsors, and that substantially controls journals, medical associations, and related foundations (through direct support and/or advertising). Such phenomena operate in all branches of medicine, including psychiatry.

The narrative that sugarcoats antidepressants for med students and trainee psychiatrists is in turn an influence on their prescribing patterns and decisions. Fava put this well in an interview last year with Psychiatric Times when stressing: “If you teach a psychiatric resident that symptoms that occur during tapering cannot be due to withdrawal, he/she is likely to interpret them as signs of relapse and to go back to treatment (exactly what “Big Pharma” likes).… These clinicians actually perceive a state of distress in their patients but have been taught only to think in terms of harmless medications. They are often unaware of the major advances that have been made in psychotherapy in the past decades, far superior to the pharmacological ones.”

In the book, these assumptions can seem so omnipresent and overwhelming that they sometimes lead Fava to conclude that he is “swimming against the tide of pharmaceutical propaganda.”

Nevertheless, his insistence on tackling “long-term outcomes” for drugs that psychiatrists and other physicians continue prescribing in large numbers means that he is in a position to address such pressing related matters as: drug tolerance and risk from higher dosage; the poor fit between SSRIs and anxiety disorders; and why pharmacological interventions can “trigger cascade iatrogenesis,” or multiple adverse events downstream, including emotional blunting and a syndrome now recognized as post-SSRI sexual dysfunction (PSSD).

In addition, Fava calls the concept of “treatment resistance” “ill-defined” and “questionable,” because it is “based on the untested assumption that treatment was right in the first place.” In this last scenario, “failure to respond is shifted upon patients’ characteristics,” implicitly blaming them for nonresponse while reaffirming drug treatments as optimal and preferable when they may be neither.

A quieter, no less important argument throughout the book is that “biological reductionism has resulted in an idealistic approach, which is quite far from the explanatory pluralism required by clinical practice.” The decision to relabel as “mild” and “self-correcting” what in practice are often chronic long-term withdrawal symptoms of a medical origin can be seen as a key element of that “idealism,” in that it presents a narrative about SSRIs and SNRIs that is empirically at odds with clinical phenomena.

Fava’s book joins a cluster of new and significant writings on antidepressant prescribing and withdrawal, whose publication points to a shared understanding of the magnitude of the problem. They include James Davies’ critique of psychiatric reasoning in Sedated: How Capitalism Created Our Mental Health Crisis (2021); Beverley Thomson’s patient-centered analysis in Antidepressed: A Breakthrough Examination of Epidemic Antidepressant Harm and Dependence (2022); and Michael P. Hengartner’s Evidence-biased Antidepressant Prescription: Overmedicalisation, Flawed Research, and Conflicts of Interest (2022).

Of these, Hengartner’s focus on the “economies of influence” compromising clinical trials and distorting the scientific profile of antidepressants is closest to Fava’s, particularly in his final chapter, “Solutions for Reform,” on how corporate bias affects medical research. Fava’s closing chapter is called “A Different Psychiatry Is Possible,” and it includes recommendations for macroanalysis and “thinking ‘iatrogenic,’” for safer, individualized forms of treatment and tapering that also involve psychotherapy.

Overall, Fava’s book urges us to look at “the major health problems caused by inappropriate prescriptions of antidepressant medications” and their “highly disappointing results.” In its concise telling and helpful practical recommendations, Discontinuing Antidepressant Medications is a book also marveling that, more than two decades after SSRIs and SNRIs were first approved for use, we “still have so little scientific information to deal with [their] key clinical issues,” notably those tied to toxicity, dependence, and withdrawal.

References

Davies, J. 2021. Sedated: How Capitalism Created Our Mental Health Crisis. Atlantic Books [Link].

Fava, G. A. 2021. Discontinuing Antidepressant Medications. Oxford UP [Link].

Hengartner, M. P. 2022. Evidence-biased Antidepressant Prescription: Overmedicalisation, Flawed Research, and Conflicts of Interest. Palgrave Macmillan [Link].

Thomson, B. 2022. Antidepressed: A Breakthrough Examination of Epidemic Antidepressant Harm and Dependence. Hatherleigh Books [Link].