SSRIs

Antidepressants and Major Depressive Disorder

New studies show minimal improvement over placebo but continued risk of harm.

Posted October 7, 2019 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

“The benefits of antidepressants seem to be minimal,” conclude three experts on antidepressants and clinical intervention in the latest issue of the British Medical Journal. “Antidepressants should not be used for adults with major depressive disorder before valid evidence has shown that the potential beneficial effects outweigh the harmful effects.”

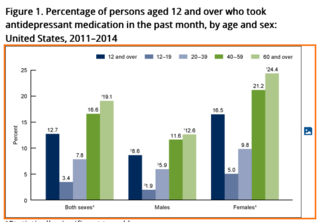

The stark conclusion by authors Irving Kirsch (Harvard Medical School), Janus Christian Jakobsen, and Christian Gluud (both at Copenhagen University Hospital) stands against the backdrop of a continued rise in prescriptions for antidepressants worldwide. In the U.S. alone, according to the 2017 data brief from the National Center for Health Statistics, “antidepressant use increased nearly 65% over a 15-year time frame” between 1999 and 2014.

The World Health Organization estimates that major depressive disorder affects “more than 300 million people globally,” the researchers note, making depression the leading cause of disability. That, in turn, has fueled a global demand for SSRI antidepressants. According to the same NCHS data brief, again pinpointing to the U.S., “about one in eight people aged 12 and over reported taking antidepressants during the previous month.”

Consider the implications. On the one hand, comparable studies concluding similarly that antidepressants show minimal improvement over placebo have been repackaged to suggest that the drugs have anxiolytic [anxiety-reducing] effects and could be prescribed for anxiety instead. Here, the outcome switching would be less glaring a problem for patient health and public health if, for more than two decades, the same drugs had not been sold as reliable and mostly safe treatments for depression.

On the other hand, the BMJ article confirms a spate of recent meta-studies showing that adverse effects and withdrawal from SSRI antidepressants are frequently more serious and longer-lasting than current guidelines indicate. That patients are reporting difficulties stopping treatment at the same time that officials are asserting that the drugs are not addictive. And just one-in-five patients are being warned about the potential risks of antidepressants.

In a second, recent study of SSRI antidepressants, “an umbrella review of 45 meta-analyses of observational studies” published last week in JAMA Psychiatry, more than a dozen European and North American researchers reported that there was “convincing evidence … for the associations between antidepressant use and suicide attempt or completion among individuals younger than 19 years,” as well as “for associations between antidepressant use and autism risk among the offspring.” After “adjusting for confounding by implication” (that is, for studies already controlling for a psychiatric condition), however, the same researchers, many of them declaring multiple ties to drug companies, nonetheless concluded that “antidepressant use appears to be safe for the treatment of psychiatric disorders” and that “most putative adverse health outcomes associated with antidepressant use may not be supported by convincing evidence.”

Again consider the implications. Apparently “convincing evidence” of “associations” between antidepressant use and suicide attempt, as well as between SSRIs and autism risk, ends with a conclusion about drug safety that is itself confounding. Among other things, it points to a logical fallacy at the heart of the article. As Zurich-based researcher Michael P. Hengartner observed of a study that takes all reported adverse effects as “putative,” “Absence of convincing evidence for severe harm is not evidence of safety… To claim that antidepressants are safe you need to provide convincing evidence that antidepressants don’t cause harm. That is not the case here.”

Industry involvement in research is one of several factors Kirsch, Jakobsen, and Gluud invoke in the BMJ as contributing to a “high risk of ‘for profit’ bias.” Meta-analyses that include an author who was also an employee of the manufacturer of the drug studied were, they note, “22-fold less likely to have negative statements about the drug than other meta-analyses.” Meanwhile, a 2017 study of industry sponsorship and research outcomes found that industry involvement by the manufacturing company was significantly more likely to “lead to more favorable results and conclusions than sponsorship by other means.”

Another key factor influencing the outcome of trials and their corresponding meta-analyses: most trials and reviews are non-systematic and assess only short-term effects—that is, over roughly four to eight weeks. The long-term effects of antidepressants remain unclear, they conclude, because the research needed to make such a determination largely does not exist.

As do the authors of the JAMA Psychiatry review, Kirsch, Jakobsen, and Gluud conclude that it is “of utmost importance to consider the clinical relevance of statistically significant results when assessing the effects of antidepressants.”

Yet despite the biases, they can pinpoint as “inflating beneficial effects of review results,” those same studies “show only negligible differences between antidepressants and placebo on depressive symptoms, and the ‘true’ effect of antidepressants might not even be statistically significant.” The adverse effects that this and many other reviews document stubbornly remain.

Here, then, is the core dilemma facing researchers, physicians, and their patients: Both articles constitute significant recent reviews of SSRI antidepressants. They appear just days apart in journals bearing equal prestige and authority on either side of the Atlantic. The JAMA Psychiatry review authors, declaring multiple conflicts of interest, state that adverse effects are “putative” and that “antidepressant use appears to be safe for the treatment of psychiatric disorders.”

The review with which we began, from experts reporting no competing interests in the journal’s British counterpart, reaches close to the opposite conclusion: “Antidepressants should not be used for adults with major depressive disorder before valid evidence has shown that the potential beneficial effects outweigh the harmful effects.”

With psychiatry seemingly divided over such fundamental matters of evidence and validity, the Hippocratic oath must doubtless reassume priority. Its overwhelming concern is for patient well-being and safety: “First, do no harm.”

References

Dragioti E, Solmi M, Favaro A, et al. Association of Antidepressant Use With Adverse Health Outcomes: A Systematic Umbrella Review. JAMA Psychiatry (October 2, 2019). doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2859 [Link]

Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, and Kirsch I. Should antidepressants be used for major depressive disorder? BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. Epub ahead of print (September 26, 2019). doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2019-111238 [Link]