Health

A Force More Powerful Than Anti-Vaxxers? Economics!

If We Pay, Vaccines Will Come

Posted October 6, 2016

We have a vaccine crisis in the this country. Not just the one caused by anti-vaxxers like Jenny McCarthy, scaring Americans away from life-saving childhood vaccines with pseudo-scientific claims about autism. Instead I’m talking about a bigger crisis, one caused by a dangerously thin supply of vaccines. Wise parents who ignore the blatherings of people like McCarthy may soon arrive at their pediatricians’ offices prepared to vaccinate their children, only to find out there is no vaccine.

To protect supplies, we need to be sure we are paying well for the vaccines we receive.

That’s the conclusion of a study led by my friend and colleague David Ridley. Working with two graduate students, Ridley analyzed whether the likelihood of vaccine shortages was correlated with the price of the vaccine. You see, the majority of childhood vaccines in the U.S. are purchased by the federal government, as part of a Vaccines For Children Program created by congress to provide vaccines to low-income kids. In purchasing these vaccines, the government uses a “cost-plus-pricing” model. This model establishes the marginal cost the manufacturers incur to produce a dose of vaccines and marks the final price up a titch, to give companies a small profit. This mark-up is pretty modest, however, especially for older vaccines. Such modest profits reduce manufacturers’ incentives to invest in vaccine production.

Shouldn’t a modest profit be enough to keep manufacturers in the market?

Unfortunately, it’s not enough of an incentive to avoid shortages. Vaccines can be complicated to manufacture. Inevitably, production lines get disrupted by contamination issues or other problems. If there were lots of excess production capacity, an occasional disruption wouldn’t matter. But many vaccines are manufactured by only one or two companies, and with very little excess capacity built into the system. Excess capacity, after all, is expensive to maintain. So when a production problem arises for an older, less expensive vaccine, often a shortage follows.

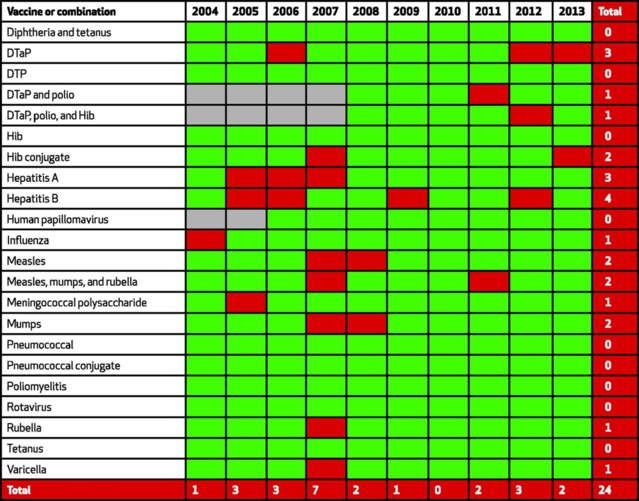

Here is a picture of which vaccines have experienced shortages in the U.S. since 2004, signified by red squares:

You won’t be surprised at what Ridley, a health economist, offers as a solution to these shortages. He wants us to pay more money for vaccines. In his analyses, in fact, Ridley found that a 10% increase in the price of a vaccine was associated with a 1% reduction in the chance that this vaccine would experience a shortage the following year. Pay generously enough for vaccines, and more manufacturers will compete for business, or the manufacturers already in the marketplace will invest in excess production capacity so as to not lose out on business when production problems arise.

How much should the government pay for childhood vaccines? There is no simple answer to the question. However, in negotiating prices with manufacturers, government purchasers should acknowledge that when vaccine profits become too slim, so too do vaccine supplies. Price negotiations need to set a balance between protecting public purses and promoting public health.

***Previously Published in Forbes***