Career

The Waiting Game

A matter of social intelligence: Don’t make your cooperation partners wait.

Updated March 17, 2024 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Making others wait is a risky power move.

- A waiting game can be described as an ultimatum game.

- The socially intelligent strategy is to not let others wait.

Godot was here. You just missed him. – Hoca Camide

Imagine you are doing a project with a colleague. There is a due date and the two of you work in sequence. Vladimir (you are Estragon) is working on his part and you are waiting to take over to finish the project. You never made an agreement with Vladimir to turn the work over to you at halftime, but you take it as a reasonable expectation that he will. But he doesn’t. The clock keeps ticking and you are getting restive.

At last, after 80% of the available time has passed, Vladimir sends you the work to complete it. Will you do it, perhaps with resentment, but will you do it? What if 90% of the time had passed? Suppose you are still able to finish the work, but the resentment is now greater. At what point will you say no, with the effect that neither you nor Vladimir will get the benefit of the completed work—if there is such a point?

The basic scenario is easy enough to imagine,and probably has a ring of familiarity. Similar scenarios can be imagined for any context in which one person waits for another in order to complete a joint affair. Being picked up for a date or any type of joint venture meets the structural requirements of this game.

The amount of time left is a variable. As this time window narrows, the risk for the first player to meet with the second player’s veto increases because the second player’s resentment increases. When the second player finally says no, we have a case of moral punishment because the second player destroys value for the first player at a cost to himself.

This interactional game shows the general features of the ultimatum game. By the lights of self-interested rationality, the first player (let’s call this person the Sender) will take as much time as he (she, they) thinks he can get away with. The second player (the Receiver) will not refuse to finish the work if it is still possible to be completed. The Receiver will manage his resentment, keep calm, and carry on.

By the lights of social rationality, however, the receiver will set an internal deadline, on the other side of which the resentment exceeds the benefit of completing the work with extra effort and haste. A socially intelligent Sender knows this and passes on the work on time. The interest of psychology here is how players will negotiate the conflict between material rationality and social rationality.

To simplify the scenario, assume that the time the Sender leaves to the receiver is 20% of the total and both players become aware of their preferences. The Sender would love to defect, that is, take 80% of the time and have the Receiver be compliant. The second-best option is to cooperate by using only 50% of the time and have the Receiver accept that. The third-best option is to defect by dragging things out and be met by the Receiver’s veto. The worst option is to cooperate and see the Receiver walk away from the project anyway.

The Receiver has a different set of preferences. He would, of course, prefer to receive the work on time, and he’d be happy to cooperate. The second-best option, which delivers the warm glow of righteous punishment, is to refuse to complete the job when the Sender fails to provide a fair amount of time. The third option is to refuse a fair offer, as this would induce guilt. Finally, accepting an unfair arrangement would be worst, as it might bring shame.

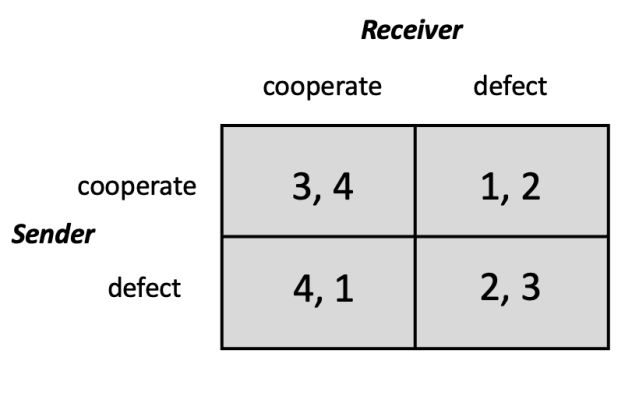

The preference matrix above shows the two players’ preferences, with the Sender’s preferences to the right and the Receiver’s preferences to the left in each of the four cells, and higher numbers representing stronger preferences. Clearly, the case of mutual cooperation is most efficient overall. It leaves the Sender, however, with the unrealized alternative of doing better with defection. Yet, a Sender who contemplates a switch to defection must understand that the Receiver would then have an incentive to defect as well, in which case a state of mutual defection is reached from which there is no escape. With mutual defection, neither player can do better by unilaterally switching to cooperation.

In this ultimatum game, mutual defection, as in the prisoner’s dilemma, is a Nash equilibrium (see Krueger, 2020, for a version of the ultimatum game without a Nash equilibrium, and Krueger, 2018, for a description of a Gullibility Game, which shares this payoff matrix). The traditional game theorist is of two minds here. On the one hand, as noted above, material rationality dictates that the Receiver will not abandon a project if there is enough time left to complete it. On the other hand, if social preferences are laid out, and if they take the form shown in the matrix, the game theorist assumes that players will end up in the tragic place of mutual defection.

Is there, then, hope? A socially intelligent Sender anticipates that his defection will trigger the Receiver’s defection, which will hurt both. Knowing this, the Sender will cooperate, triggering cooperation as the Receiver’s best response. The intelligent Sender knows his own outcome is better under mutual cooperation than under mutual defection and that his unilateral defection would not stand (Krueger & Grüning, 2024).

This analysis assumes that players can respond to each other and change their strategies as they go. This allowance eliminates uncertainty. If, however, both players select their strategy without knowing what the other will do, outcomes become fragile. A meta-intelligent Sender may anticipate the Receiver’s expectation that the Sender will dutifully cooperate, and then this Sender will make a play for the sweet payoff of unilateral defection. In turn, however, a smart Receiver might anticipate this move, and back we are in the circle of hell of mutual defection.

At the end of the day, it is the risk-averse Sender who enables the socially most efficient outcome by honoring the expectation that his work will be done and delivered in time. Wouldn’t it be nice if there were more Senders like this? Where is Godot when we need him?

References

Krueger, J. I. (2018). The gullibility game. Psychology Today Online. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/one-among-many/201806/the-gullibility-game

Krueger, J. I. (2020). Trust and power in the ultimatum game. Psychology Today Online. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/one-among-many/202003/trust-and-power-in-the-ultimatum-game

Krueger, J. I., & Grüning, D. J. (2024). Dostoevsky at play: Between risk and uncertainty in Roulettenburg. In S. Evdokimova (ed). Dostoevsky’s The Gambler: The allure of the wheel: (pp. 59-86). Lexington Books.