Perfectionism

The Sweet Spot of Perfectionism

When does perfectionism become dysfunctional and what can you do about it?

Posted February 1, 2024 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

At the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, the 14-year-old Romanian gymnast Nadia Comăneci achieved something unprecedented: She performed a flawless routine on the uneven bars, becoming the first person ever to score a perfect 10 at the Olympics. She showed that the pursuit of perfection can lead to remarkable achievements.

Perfectionism is a character trait that is more common in certain professions, such as top athletes, musicians, and medical specialists (Lemaire 2014; Perfectionism in Sport and Dance 2014; Skoogh 2019). A concert pianist who can flawlessly play a Rachmaninov piano concerto receives thunderous applause. Likewise, a surgeon who works with precision and attention to detail is less likely to make mistakes during surgery. Perfectionism is generally appreciated as a quality. It's therefore not surprising that perfectionism in society, particularly among young people, has been on the rise for years (Curran and Hill 2019).

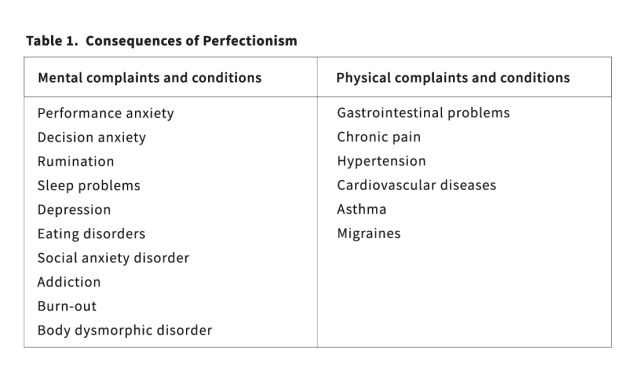

However, there is a dark side to perfectionism. It is associated with a wide range of both mental and physical health issues. Individuals with high levels of perfectionism often experience depression, social anxiety disorders, addiction, burnout, and sleep problems (Limburg 2017; Ocampo 2020). Moreover, it increases the risk of physical conditions such as migraines, high blood pressure, heart disease, asthma, and chronic pain [Table 1] (Ocampo 2020; Molnar 2017).

Given the growing societal emphasis on perfectionism, this trend is likely to result in more people experiencing health problems. The crucial question is: How can we strike a balance between the different aspects of perfectionism? The short answer is that we should aim for what I call the "sweet spot of perfectionism." But how can we achieve that?

The Different Forms of Perfectionism

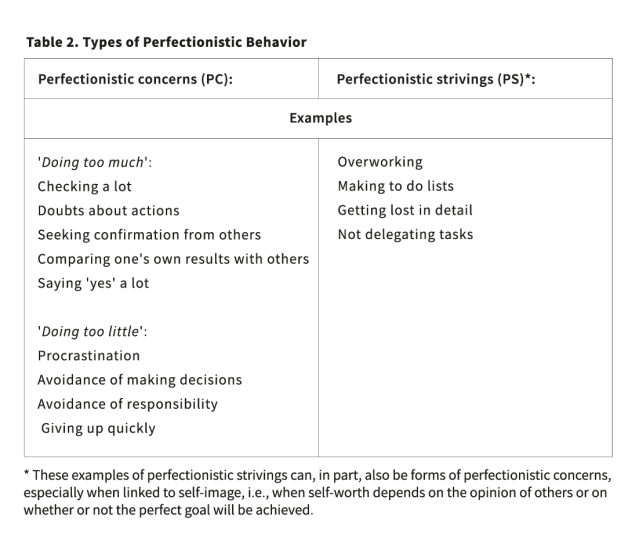

To identify this sweet spot, we first need to understand the different forms of perfectionism. Perfectionism can be divided into two dimensions: perfectionistic concerns (PC) and perfectionistic strivings (PS) (Stoeber and Otto 2006).

Perfectionistic concerns (PC) involve doubts about choices and actions, fear of making mistakes, and worrying about how others judge them. Individuals with high PC are often plagued by self-doubt and base their self-worth on whether they achieve specific goals or what others think of them [Table 2]. This type of perfectionism is often described as socially prescribed perfectionism.

It's evident that all of this contributes to many negative social interactions and stress-related symptoms. High levels of PC are associated with various health problems: it increases the risk of burnout, anxiety disorders, and depression (Limburg 2017). The less PC you have, the healthier you are likely to be.

Perfectionistic strivings (PS), on the other hand, revolve around pursuing perfection. People with high PS set extremely high goals and are highly organized. PS is primarily self-oriented perfectionism and appears to promote good health. This is consistent with the findings of many studies: A high degree of PS leads to more positive emotions, better health, and a reduced risk of burnout (Sirois 2016; Childs 2010). The relationship, therefore, appears to be linear in the opposite direction: More PS leads to less illness.

However, there's something contradictory at play here. Other studies suggest that high levels of PS may actually increase the risk of depression and anxiety disorders. Moreover, high levels of PS are often observed in individuals with eating disorders (Limburg 2017).

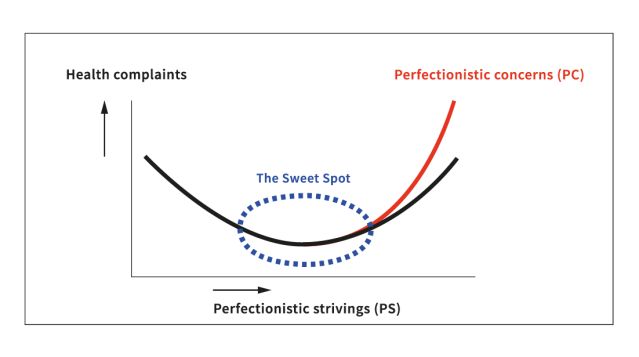

How do these seemingly contradictory findings align? I propose that the relationship between PS and health follows a U-shaped curve [see Figure 1]. This means that both too little and too much PS may be unhealthy.

Too little PS leads to a lack of initiative and lack of improvement for those experiencing health issues. Without setting goals, progress is hindered, and symptoms persist. However, excessive PS is also detrimental, as it can result in unrealistically high goals, frequent failures, despair, crossing one's limits, and, subsequently, more health issues (Hill 2004; Hill 2016). It is crucial to strike a balance, not having too much or too little PS.

Where Is the "Sweet Spot"?

Everyone has a certain degree of both PC and PS—so how are they interrelated? There is evidence that the presence of both high PC and high PS acts as a catalyst (Hill 2016). This means that the combination of both leads to even more health issues. PC alongside PS intensifies problems, acting as a multiplier for health problems.

To reach the "perfect" level of perfectionism, then, it is important not to have too much or too little PS, along with a low level of PC. This is the "sweet spot of perfectionism" [see Figure 1].

How to Reach the Sweet Spot

Now that we know what to focus on, the question is: How do we get there? The answer is complex, because individual traits are intertwined with broader societal developments. These include the increasing emphasis on societal achievements, which encourages competitiveness and individualism. In an environment that highly values perfection, organization, and the reduction of mistakes, individuals with perfectionistic tendencies are further driven toward perfectionism. Such societal developments are difficult for individuals to influence.

However, it is very possible to reduce one's own perfectionistic tendencies. To do so, it is crucial to identify steps that individuals can take to better balance their own perfectionism. In my view, the following five pillars can serve as guidelines:

- Insight: Gain insight into your own forms of perfectionism. Is it primarily a high level of PC? Or is there also an excess of PS? It's important to understand how this perfectionism is linked to your self-worth. Is it about achieving lofty goals or seeking approval from others? Recognizing perfectionistic behavior can be helpful [Table 1]. For instance, is there evidence of overworking and excessive attention to detail? This may indicate a high level of PS. Alternatively, is there more procrastination, self-doubt, and avoidance of responsibilities? Such behaviors may point to high PC.

- Kindness: Be kind to yourself, in how you think and speak about yourself. Perfectionism often comes with high and strict standards, where failing to meet them results in self-criticism. Although setting high goals is beneficial, negative self-critique is never functional (Werner 2019).

- Vulnerability: Dare to be vulnerable. Doubt and uncertainty are part of personal growth. Moreover, it's important to communicate about them, both with colleagues and loved ones. Openness can lead to support, understanding, and especially connection.

- Concrete, achievable goals: Are the goals you set realistic? Some may prefer smaller, more attainable goals, while others may opt for more complex career goals. Setting realistic goals is also a form of insight.

- Balance: A balanced lifestyle contributes to overall well-being. It involves finding the right equilibrium between adequate physical activity and rest, healthy and varied nutrition, as well as providing ample room for social interactions and support. This balance will be different for each individual but is essential to maintain.

Conclusion

Changing perfectionistic tendencies is not an easy path. Altering behavior and habits is challenging and involves ups and downs, but it is possible. Moreover, the necessity is clear if we want to better shield ourselves from the dark sides of perfectionism.

References

Childs JH, Stoeber J. Self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism in employees: Relationships with burnout and engagement. J Workplace Behav Health. 2010;25:269-81

Curran, T., & Hill, A. P. (2019). Perfectionism is increasing over time: A meta-analysis of birth cohort differences from 1989 to 2016. Psychological Bulletin, 145(4), 410–429.

Hill, R. W., Huelsman, T. J., Furr, R. M., Kibler, J., Vicente, B. B., & Kennedy, C. (2004). A New Measure of Perfectionism: The Perfectionism Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 82(1), 80–91.

Hill, A. P., & Curran, T. (2016). Multidimensional Perfectionism and Burnout: A Meta-Analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20(3), 269–288.

Lemaire JB, Wallace JE. How physicians identify with predetermined personalities and links to perceived performance and wellness outcomes: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:616.

Limburg K, Watson HJ, Hagger MS, Egan SJ. The Relationship Between Perfectionism and Psychopathology: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73(10):1301–26.

Molnar DS, Sirois FM, Flett GL, Janssen WF, Hewitt PL. Perfectionism and health: The roles of health behaviors and stress-related processes. In: Stoeber J, editor. The Psychology of Perfectionism: Theory, Research, Applications. 2017. p. 200–21.

Ocampo ACG, Wang L, Kiazad K, Restubog SLD, Ashkanasy NM. The relentless pursuit of perfectionism: A review of perfectionism in the workplace and an agenda for future research. J Organ Behav. 2020;41(2):144–68.

Perfectionism in Sport and Dance. (2014). International Journal of Sport Psychology, 45(4), 265–407

Sirois FM. Perfectionism and Health Behaviors: A self-regulation resource perspective. In: Sirois FM, Molnar DS (eds). Perfectionism, Health, and Well-Being. Chapter 3. Cham: Springer International Publishing Switzerland; 2016. p. 45-68

Skoogh, F., & Frisk, H. (2019). Performance values - an artistic research perspective on music performance anxiety in classical music. Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education, 03(01), 1–15

Stoeber, J., & Otto, K. (2006). Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(4), 295–319.

Werner AM, Tibubos AN, Rohrmann S, Reiss N. The clinical trait self-criticism and its relation to psychopathology: A systematic review - Update. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:530-47