Parenting

Parenting by Experiment Can Do Harm to Babies

Parenting advice too often counters what helped our ancestors adapt.

Posted February 23, 2022 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Parents often seek childrearing advice in the results of experiments on babies.

- It's important to know how studies are done before accepting the information as valid.

- Assess how researchers are using the tools of science.

Our species evolved to need the components of our evolved nest to grow in healthy, resilient ways. This is especially true for babies, when brain development is rapid, occurring every second. And a birth, human infants are more immature than other primates, and with much more growing to do, require more extensive care.

We know now that early stress can be toxic to babies (e.g., Garner et al., 2021; Shonkoff & Garner, 2012; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2001). Most of the information on the specific effects (from dysregulation of biological systems to long-lasting epigenetic changes) of missing pieces of the evolved nest comes from studies done on animals kept in cages (e.g., Harlow, 1958) or whose brains can be cut up afterward (e.g., Meaney, 2001). Since we are mammals with similar brain structures, we can draw conclusions on the effects of experiences on brain development and function.

Research experiments often do not take our evolved baseline needs into account when designing and testing ways to treat babies. Experiments are conducted that violate babies’ basic needs (e.g., for touch, caregiver presence, responsiveness). Nevertheless, some parents look to experiments for deciding how to treat their baby.

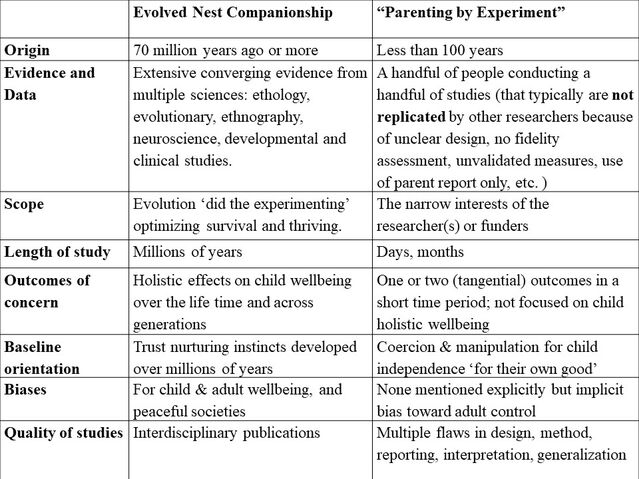

Parents often consult contemporary research findings for child-rearing information The table below contrasts two general approaches to childraising, one that provides evolved-nest companionship and one that follows experimental findings, which I call Parenting by Experiment. Notice the deep history and broad science that comprises the first way and the recent, limited approach of the second way. The second way often ends up violating the first way because of its limited scope and poor methods used in research.

My research supports two pieces of advice for those looking for childrearing advice: (1) Understand the problem with experiments on babies, and (2) learn how to evaluate a research study based on the broad understanding of humanity and its needs.

1. You can’t really do experiments on babies.

- It is unethical. You should not randomly assign babies to treatments that may harm them.

- Every baby develops at her own rate and is a different baby every few minutes (the entanglement of nature and nurture), so you cannot generalize results in any specific way.

- You can create poorly constructed "experiments" (poor design, poor monitoring, not blinded, not controlled). For example, the “intent to treat” method (ITT) often used in medical research testing drugs, but also in sleep training research, is intended for drug trials but misused for baby studies. It ignores noncompliance, withdrawal, and anything that happens after randomization to a treatment group. In psychology, we know that fidelity of implementation is a key factor in judging whether a particular intervention worked as intended.

- What is missing in virtually every study that advocates unnested care for babies (e.g., sleeping alone) is a comparison with our species’ baseline for what is normal, what babies need—the practices and outcomes of the evolved nest over the long term.

2. Learn about how to evaluate a research study.

Science is a tool. It has many aspects. It’s important to have a broad understanding of science. Some sciences are more observational and descriptive (e.g., anthropology, biology), some are experimental (e.g., physics, chemistry) and others use a combination of methods (e.g., psychology). Each science attempts to have rigorous tools for assessing valid study designs and methods, as well as analyses and interpretations of findings.

In assessing what is good for a human being, you need to take into account multiple branches of science that study human outcomes: evolution, ethology, archeology, anthropology, neuroscience, clinical, developmental. “Evidence based” for deciding about meeting babies’ needs must mean including a broad sweep of information from across relevant sciences.

Understand that experimental studies of rapidly developing babies provide limited information. They isolate variables and test people in unusual ways, making it hard to apply findings to real life, where every individual is unique, every individuals is dependent on relationships, and everything about a person and relationships interact.

Importantly, assess how researchers are using the tools of science:

- Do the researchers “have skin in the game” (i.e., they depend on the study outcomes for their income, reputation, their group’s or their funder’s ideology)?

- Overall, do the conclusions fit with our species history, needs, development, and known clinical outcomes?

- Do the results examine the long-term outcomes across years into adolescence and adulthood in terms of multiple health outcomes?

- Do the results fit with your heart-of-heart instincts for what is best for your child? Parents have built-in instincts that evolved too!

Conclusion: Findings from a few “experiments” cannot compete with the millions-year-old ‘"experimenting" that evolution has conducted to find out what helps humans survive, thrive, and reproduce across generations. It is appropriate to question the findings of studies that conclude that violations of evolved nest practices are "safe."

References

Garner, A., Yogman, M., Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Council on Early Childhood. (2021). Preventing childhood toxic stress: Partnering with families and communities to promote relational health. Pediatrics, 148(2), e2021052582

Harlow, H. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 673-685.

Meaney, M. J. (2001). Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24, 1161–1192.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Garner, A. S. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232-246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington DC: National Academy Press.