Intelligence

Closing the Gap Between Insight and Action

The biases that keep us from acting, and the actions we can take against them.

Posted September 30, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Thoughts are typically less effortful (cost less, require less repetition) than actions.

- Intellectual insights often aren’t useful guides to action.

- Ideology can block belief in the possibility and/or appropriateness of action.

Having explored a couple of them in the previous part of this post, here, I round up the rest of the big reasons why action so often takes a backseat to reflection.

3. Thoughts cost less than actions.

The reason:

As I pointed out in Part 1, actions come with resource costs. Of course, thoughts do too, but they come a lot cheaper. So if you can get away with just doing some thinking, inferencing, and pattern-matching, then you get the interpretive satisfaction and perceived significance outlined in points 1 and 2 without the costs of actually doing anything.

The trouble is that cognitive dissonance naturally arises when you reach a convincing conclusion you don’t act on: You’ve now set up a conflicted situation in which your knowledge and actions are at odds with each other—and cognitive dissonance is unpleasant. So to get rid of it, what you need is not just to do the low-cost thinking, but also to give yourself good enough reasons for not changing anything in response.

This is where cognitive dissonance reduction kicks in. It's a highly honed human skill, and it can work wonders, as long as the miracle you want is to reduce discomfort at the cost of preventing problem-solving. This is the tradeoff because, by definition, you’re persuading yourself that the problem isn’t as serious as it might seem, that the costs of action are too high, its probability of success is too low, or whatever, in order to make yourself feel better about inaction.

If you convince yourself that it was always inevitable that you would have an eating disorder and that now after 20 years, it’s clear that you’ll always have it, for example, or if you tell yourself that having no compulsive exercise tendencies sounds idyllic but that everyone remotely healthy does exercise they don’t really feel like doing, then that extra little bit of cognitive activity saves you the effort of actually trying to solve the problem.

The response:

I guess there are three main options here:

- Improve the (perceived) cost/benefit ratio for taking action

- Worsen it for thinking

- Block the cognitive dissonance reduction

So you might:

- Devise very small specific problem-solving actions to take (as in point 1)

- Tell someone else your cognitive conclusions, so it’s not just you who knows you’re not doing anything about them

- Identify a common dissonance reduction tactic you tend to employ (e.g. trivializing or distracting yourself from the costs of the conflict) and invent a way to impede it (e.g. starting some daily journaling where you make a point of giving yourself space to think about what the disorder is actually doing to your life)

4. Thoughts can be one-offs; actions usually can’t.

The reason:

There’s a particular kind of structural mismatch between insight and the corresponding actions that contribute to making the former easier. With insights, though they may take time and effort to formulate, once you’ve achieved one, it often has a “one shot and you’re done” feel to it.

I might conclude, say, that the disordered habits I keep repeating seem to make little sense, given my explicit priorities reflected a profound need I hadn’t previously acknowledged to myself. Once I’ve reached that conclusion and it has a certain minimum satisfaction rating (i.e. it makes enough sense of enough things without making too many implausible assumptions), I’m done; I’ve got my payoff.

Conversely, there are very few one-shot actions that get you high satisfaction in one go. Truly conclusive actions are rare, and many pivotal actions (eating breakfast tomorrow, having a binge-free day tomorrow) are merely the starting point for the multiple repetitions with variation and progression that are needed to get you what you want (e.g. recovery).

The response:

Seek out actions that have as many of the benefits as possible of one-shot solutions. For example, design them to have immediate payoffs (e.g. a change to your eating or exercise habits that instantly feels better than the previous norm) or to bring about cascades of other changes (for example, stopping checking calorie counts on labels helps you count calories less in your head, which makes it easier to concentrate on other things, which makes it easier to be less preoccupied with the idea of weighing yourself, which makes it easier to eat generously).

5. Insights tend to apply at the wrong level of detail.

The reason:

Verbalized intellectual insights tend to operate at a high level of generality, e.g. my eating disorder revolves around my lack of self-esteem, or, slightly less vaguely, around my unwillingness to demand more than the merely tolerable for myself, while tiring myself out trying to help others live better. This type of insight might generate something that feels like a plan of action: I need to bolster my self-esteem / start being more assertive / leave my job / starting listening to my body’s needs / eat more / run less. But even the last of these, which sound the most practical, aren’t particularly useful as direct guides to action. What you really need to make it likely that you’ll take and sustain meaningful action is something more like “I need to stop running for a month, and then use questions x, y, and z to reassess whether it’s safe for me to try out some other kind of physical activity (not endurance cardio) that I’ll research in the meantime”.

The response:

In any life domain where stasis is the default (e.g. recovery), practise developing your insights into guides to action at a useful level of specificity, usually the more the better, including contingency planning as well as “how will I know whether I’ve succeeded?” criteria.

6. High-level fatalism is infectious.

The reason:

Believing certain things about the structure of the universe and your place in it makes effective action more or less likely. If, for example, you believe that there’s a divine plan and your suffering is happening for a reason, you may be less likely to do anything about it. Ditto if you believe everyone else’s suffering matters more than your own, a belief that often comes in “I don’t deserve anything better than this” clothing. Even if you don’t have any obvious high-level beliefs blocking your inclinations to act, the belief prerequisites for action may be missing: Seeking and taking satisfaction in intellectual insights requires you to believe only that the universe makes some sense; taking action, meanwhile, requires you also to believe yourself capable of change and deserving of it (or at least not undeserving, or alternatively indifferent to the entire concept).

The response:

Changing high-level beliefs is one of the most effortful cognitive things we can do because they tend to be inculcated early on by a thousand powerful sociocultural forces, often in the form of religious packaging that’s had thousands of years to evolve (Blackmore, 1999, Ch. 15). It can be done, though, and recognising its necessity to achieving something else personally meaningful (e.g. recovery) can be a catalyst to a liberating loss of constricting ideology, even if the path there is often traumatic.

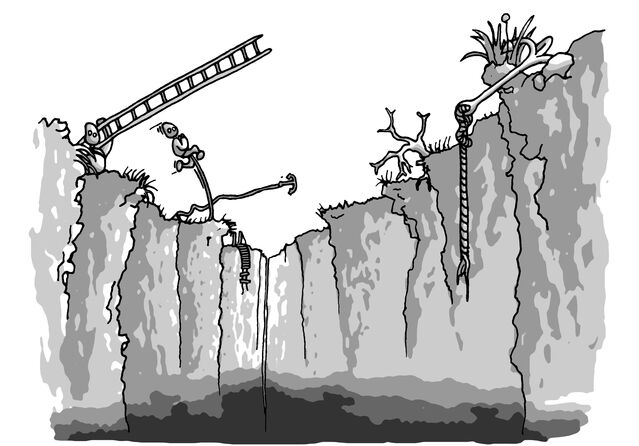

7. The gap makes itself look wider than it is.

The reason:

Alongside deferring action, another thing humans are good at, especially humans who’ve been wrecking their cognitive capacities with poor nutrition (see e.g. Grau et al., 2019), is overgeneralization, particularly with a negative slant. Quite likely your “years of doing nothing” aren’t actually that, when you observe more carefully and assess more fairly. Maybe you’ve made a couple of major recovery efforts and lots of smaller forays.

The response:

When you pretend you haven’t done anything, you prevent yourself from learning from what you have done. Instead, you could do an audit of your recovery attempts so far, mapping out rough dates and durations and then asking questions like “what went right that time?”, “what single difference could have helped it keep going right?”, “what does that tell me for this time?” Thus, by acknowledging that the gap has never been as enormous a gulf as you might otherwise have pretended, you make it much easier for yourself to bridge it for real this time.

8. The magic trick is just that.

The reason:

Ultimately, it’s crucial to remember that there is no mysterious abyss between understanding and doing. There are just many weighted probabilities for or against that first small action today and its repetition today and the day after and its variation next month. Insight is a product and change is a process, and the product needs to be treated as valuable primarily through its capacity to unleash the process.

The response:

Practise anti-magical thinking and doing whenever you can, by honouring in your everyday life the truths that there are always options, that you always learn by trying something different—and that the insight that comes from action is the kind that really counts.

References

Blackmore, S. J. (1999). The meme machine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Google Books preview here.

Grau, A., Magallón-Neri, E., Faus, G., & Feixas, G. (2019). Cognitive impairment in eating disorder patients of short and long-term duration: A case-control study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 15, 1329. Open-access full text here.