Relationships

How Ugly Was Socrates?

Why his repulsiveness may have been exaggerated.

Posted April 25, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- His students Plato and Xenophon described Socrates as ugly and made much out of this.

- His supposed repulsiveness did not prevent Socrates from leading a rich and remarkable love life.

- Plato and Xenophon may have had good reasons for inventing or exaggerating their teacher's ugliness.

Socrates was remarkably full-blooded for an ascetic philosopher. In Xenophon’s Symposium, he says, “For myself I cannot name the time at which I have not been in love with someone.” By all accounts, Socrates’s greatest love was with the famously handsome Alcibiades, who was by some 20 years his junior.

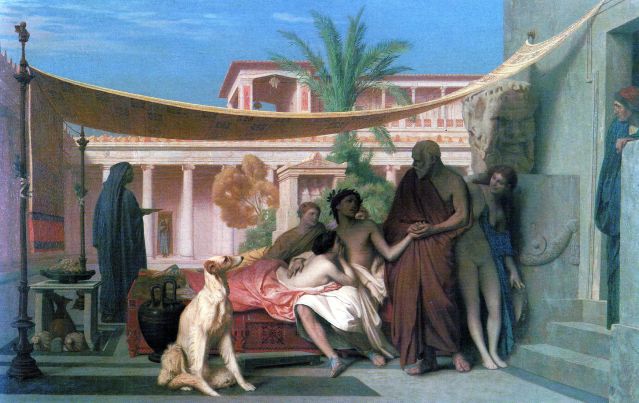

In 432 BCE, Socrates and Alcibiades fought together at the Battle of Potidaea, where the middle-aged plebeian and the young aristocrat became unlikely tent-mates. In his Life of Alcibiades, Plutarch relates that “all were amazed to see [Alcibiades] eating, exercising, and tenting with Socrates, while he was harsh and stubborn with the rest of his lovers.” In Plato’s Symposium, Alcibiades says that Socrates singlehandedly saved his life at Potidaea and, after that, let him keep the prize for valour.

At the end of Plato’s Symposium, Alcibiades confesses that he tried several times to tempt Socrates with his good looks, but each time without success. Finally, he turned the tables around and began to chase the older man, inviting him to dinner and on one occasion persuading him to stay the night. He then lay beside him and put it to him that, of all his lovers, he was the only one worthy of him, and he would be a fool to refuse him any favours if only he could make him into a better man.

Socrates replied in his usual, ironical manner:

Alcibiades, my friend, you have indeed an elevated aim if what you say is true, and if there really is in me any power by which you may become better; truly you must see in me some rare beauty of a kind infinitely higher than any which I see in you. And therefore, if you mean to share with me and to exchange beauty for beauty, you will have greatly the advantage of me; you will gain true beauty in return for appearance—like Diomedes, gold in exchange for brass.

After this, Alcibiades crept under the older man’s threadbare cloak and held him all night in his arms—but in the morning arose “as from the couch of a father or an elder brother.”

Other Lovers

Socrates also had several women in his life, the earliest, perhaps, being Aspasia of Miletus, who is mostly remembered for her relationship with Pericles, the architect of the Athenian Golden Age.

In Plato’s Menexenus, Socrates says that he learned the art of rhetoric from Aspasia, “an excellent mistress…who has made so many good speakers [including] the best among the Hellenes—Pericles, the son of Xanthippus.” Socrates agrees to recite a funeral oration that Aspasia recently wrote and taught to him. He tells Menexenus that he ought to remember the speech, since each time he forgot the words, Aspasia threatened to slap him! The speech that Socrates delivers resembles, and satirizes, the famous funeral oration delivered by Pericles and preserved for posterity by the historian Thucydides. When Socrates is done reciting, Menexenus marvels that such a fine speech could have been written by a woman.

Late in life, Socrates married the much younger Xanthippe, with whom he had three sons. That their eldest son, Lamprocles, was named after Xanthippe’s father suggests that he was the more eminent of the child’s two grandfathers.

In Plato’s Phaedo, when his friends come to visit Socrates in the state prison, they find Xanthippe sitting beside him with a babe in arms. Socrates is not long to drink of the deadly hemlock, and Xanthippe is in such a state, “crying out and beating herself,” that Socrates asks a friend to have her taken home.

Xanthippe is not otherwise mentioned in Plato, but in Xenophon’s Symposium it transpires that she had quite the temper. When a friend asks him why he does not tutor his own wife “instead of letting her remain, of all the wives that are…the most shrewish,” Socrates compares himself to an expert horseman with a fondness for spirited horses, and claims that it is precisely for her temperament that he married Xanthippe [Greek, “Yellow Horse”]—for “if I can tolerate her spirit, I can with ease attach myself to every other human being.”

There is much confusion and contradiction in later sources as to whether Socrates married twice and whether Myrto, the daughter of Lysimachus, was his first wife, second wife, concurrent wife, mistress, ward, or lodger.

His Appearance

In Plato’s Theaetetus, the geometer Theodorus describes the young Theatetus to Socrates as “very like you, for he has a snub nose, and projecting eyes, although these features are not so marked in him as in you.”

In Xenophon’s Symposium, Socrates himself says that he has protruding eyes, a snub nose, thick lips, and a paunch. He jokes that these features are to his advantage—his eyes, for instance, enabling him to “squint sideways and command the flanks.” Since Xenophon’s Symposium is set in 422 BCE, Socrates is describing himself at the age of around 48.

But despite his supposed repulsiveness, Socrates seems to have formed profound romantic attachments, including with the much younger Alcibiades, who would have topped any Golden Age list of most eligible bachelors, and the famously attractive and accomplished Aspasia, from whom he learned the art of rhetoric.

Parallels with the mythological satyr Silenus, who hid his inner beauty, may have led later writers, starting with Plato and Xenophon, to exaggerate his aberrant features. But if Socrates really did look like a satyr, why did the comedian Aristophanes, who knew him, and satirized him on the stage, not pick up on his physical appearance?

Socrates was condemned to death in part for “corrupting the youth,” and the story of Alcibiades trying and failing hard to seduce him may have been invented by Plato to help rehabilitate his reputation. In this context, making him as ugly as possible served to diminish any threat that he might have posed. It also created a golden opportunity to present wisdom, even in the ugliest of bodies, as infinitely more beautiful than the most beautiful of bodies.

Socrates, while not handsome, may not have been all that ugly. But even if he was very ugly, he, like most of us, would have been more attractive, or less repulsive, in his younger days, as a fit battle-ready hoplite.

Neel Burton is author of The Gang of Three: Socrates, Plato, Aristotle