Education

Critical Race Theory and LGBTQ-Inclusive Schools

The limits of diversity education and three ways to act.

Posted September 30, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Despite vocal resistance, prohibitive laws, and political campaign claims, there is limited evidence of CRT being taught in public K-12 schools.

- There are many obstacles to effective diversity education in schools, including racist incidents and limited funding.

- Stakeholders can support improved diversity education by speaking up.

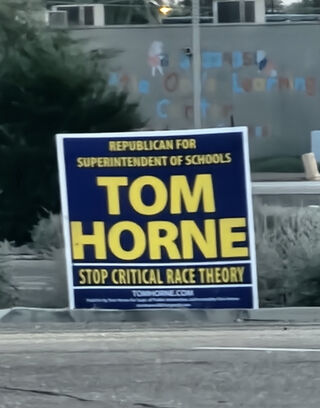

Since 2020, there have been multiple media and political dust-ups over the idea that Critical Race Theory (CRT) is being taught in schools. Local politicians are campaigning on banning CRT as their primary vote-motivator (see image) and state legislatures are passing laws that prohibit certain elements in trainings and curriculum. Some common arguments against CRT in schools are that it teaches white kids to feel guilty, is unpatriotic, and causes more racial divides.

One major problem with this “controversy” is that there is limited evidence of CRT being taught in public K-12 schools (NEPC 2021). A second problem is most folks misrepresent or misunderstand what CRT is and much opposition is based on this bad information.

In this post, I will address some challenges with diversity education in schools based on a research project I led where we interviewed equity directors about their school districts' priorities and efforts to improve the climate for diversity and equity including race, gender, and sexual diversity (Meyer, Quantz & Regan 2022). We completed these interviews in nine large urban and suburban school districts around the country in 2019 and not a single participant mentioned Critical Race Theory as informing their work.

What is CRT?

Critical Race Theory is a way of analyzing institutional structures and their impacts by centering race as the primary lens for understanding the legal system, educational inequities, and other social structures. Leading scholars of CRT used it to help make sense of why black defendants got harsher penalties from judges and juries, or why public schools disproportionately suspend and expel students of color. In one early article on CRT (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995), the authors share three central propositions to understand CRT in education:

- Race continues to be a significant factor in determining inequity in the US.

- US society is based on property rights.

- Intersections of race and property help analyze social inequity.

While later scholars have expanded on these ideas and argued that CRT should inform curriculum, pedagogy, and educational policy (Solorzano, 1997, 1998; Dixon & DeCuir 2004), there is little evidence that CRT has been taken up in meaningful ways in schools around the country.

Challenges to diversity education

The primary goal of our research project was to learn more about if and how professional development was happening related to LGBTQ equity in schools. During the study, we learned quite a bit about diversity education in general and how addressing racial disparities was often the primary priority of these professionals and their districts.

While all of our participants worked in states that had non-discrimination laws explicitly protecting LGBTQ people and reported having supportive superintendents and school boards, they still spoke at length about the many challenges they faced doing diversity education, including undoing long histories of racist policies and practices, recent racist incidents (racial slurs chanted at sporting events, nooses hung at school, etc.), limited funding and capacity for ongoing professional development on diversity topics, and teacher resistance (from a small, but vocal minority). We also learned that equity directors experienced additional barriers when they included discussions about LGBTQ people and/or gender and sexual diversity in such education efforts.

Two of the most commonly cited frameworks used in these school districts were cultural proficiency and Courageous Conversations; neither of which explicitly draw from CRT. We argue that school district diversity education initiatives would be strengthened if they were provided more institutional support and if equity directors were able to draw from CRT, queer, and black feminist theories to teach from intersectional perspectives about how oppression works. The participants themselves were often well-versed in these concepts; however, the structures of their districts often imposed limits on how they were able to implement and share their expertise.

While factions resistant to CRT and LGBTQ-inclusive policies in schools continue to organize, it is important to understand that students are more ready for these ideas than many adults. This is evidenced by the youth leading social change efforts such as #BlackLivesMatter and the recent walkouts related to the recent harmful policy changes for transgender students in Virginia. Parents, politicians, and educators who are invested in student well-being and achievement can learn from these students who are taking lessons, actions, and ideas drawn from CRT, black feminism, and queer theory. I hope they will listen.

Ways to act

- Speak at a school board meeting to request that all district staff get diversity education that helps them understand the histories and impacts of racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia.

- Send an email to your superintendent and/or school board members requesting that any new curriculum materials adopted or approved accurately represent histories and include diverse narratives about race, gender, and sexuality in the US and the world.

- Share this post with your child’s principal and teacher(s) and ask how you can help ensure this form of education happens for educators and students in your community.

References

Ladson-Billings, G., & Tate, W. F. (1995). Toward a Critical Race Theory of Education. Teachers College Record, 97(1), 47-68.

De Cuir, J. T., & Dixson, A. D. (2004). "So when it comes out, they aren't that surprised that it is there": Using Critical Race Theory as a tool of analysis of race and racism in Education. Educational Researcher(June/July 2004), 26-31.

Meyer, E. J., Quantz, M., & Regan, P. (2022). Race as the Starting Place: Equity Directors Addressing Gender and Sexual Diversity in K-12 schools. Sex Education. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2022.2068145