Evolutionary Psychology

Maladaptation in Evolutionary Psychology

How do we know when a behavior was once beneficial but no longer is?

Posted March 29, 2019

I just published an entry for the soon-forthcoming Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science (edited by husband-wife team of Todd and Viviana Weekes-Shackelford) entitled, The Maladaptive By-Product Hypothesis. Here is an introduction to the encyclopedia series, which is very large and ambitious. And here is the full entry itself, for those who can access it. (And for those who can't, please email me and I will share it with you.)

Maladaptation is an interesting phenomenon. As I define it in this essay:

In evolutionary psychology, maladaptive theory holds that some human behaviors are the result of past selective forces that are no longer operative, usually because of changes in the physical and social environment, resulting in behaviors that are no longer beneficial for fitness.

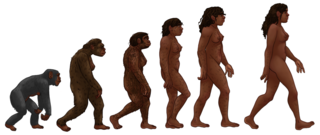

This really isn't such a stretch. Our psychology - that is, the way our brain makes sense of the world we live in, the way it computes all the inputs that bombard us, the way it executes programs as we make decisions, was slowly shaped over millions of years of time. This is why we have such strikingly similar motivations and emotions as other animals. (That similarity is the subject of my first book.)

At the same time, while the underlying instincts, motives, and emotions may be ingrained and subject to protracted selection, our precise behaviors are much harder to pin on evolution. This is even partially the case for other social mammals, but in humans, cultural evolution has overpowered biological evolution so much and for so long, that natural selection's fingerprints are extremely blurry. Evolutionary explanations of behavior are highly equivocal.

Over the last 50,000 years, and especially over the last 15,000 years, just about everything about our environment has changed dramatically. Think about how different our daily lives are from that of our ancestors a few hundred years ago. Now consider how different our ancestors from a few thousand years ago. And what about those from tens of thousands of years ago, before agriculture was invented and settlements started.

While that is a long arc in human history, it is the blink of an eye in evolutionary terms. Very little genetic evolution has taken place in that short time. For the most part, we now navigate our very modern world with brains and bodies that were shaped for a completely different existence. Maladaptation is to be expected.

Maladaptation in our bodies is often referred to as "evolutionary mismatch," and a great deal has been discovered and written about this phenomenon. If you want to read more, I highly recommend Dan Lieberman's book The Story of the Human Body and I am currently reading (and loving) Vybarr Cregan-Reid's Primate Change. But evolutionary psychology is a different beast altogether. Spotting maladaptation in our bodies is hard enough, but dissecting our minds and our behaviors is even more so. Again quoting from my essay:

As difficult as it is to apply adaptive and maladaptive interpretations to matters of anatomy and physiology, it is incredibly more so with complex behaviors. The current teleology of a behavior is difficult enough to assess on its own, especially cross-culturally, and the phylogenetic analysis is even more so. Indeed, the substantial behavioral discontinuity between humans and their extant relatives dooms many phylogenetic analyses within human evolutionary psychology.

Nevertheless, science has never been dissuaded from studying something just because it is difficult. Evolutionary psychology is a discipline fraught with challenges and controversy, but most disciplines are. If the answers were easy or obvious, we'd have them already. Science is all about devising creative means to tackle difficult problems, knowing that all discovered knowledge is tentative and no one gets the last word. The process is self-correcting, even if it takes longer than we'd like.

Back to maladaptations in evolutionary psychology. I discuss three possible maladaptive behaviors in my analysis: suicide, honor killing, and adoption. Each of these represent something of a conundrum if we attempt to understand behaviors as simple adaptations (which we shouldn't anyway). By exploring the ethology of these behaviors, we may better understand them.

The hope, of course, in analyzing human behavior is to reveal ways in which humanity might benefit from the understanding we gain. Understanding the triggers in our psyche that push us toward certain actions or patterns of behavior can be enormously helpful in undercutting or amplifying those triggers. Our evolutionarily ingrained instincts are very vague and only take shape as behaviors in the context of an environment that heavily shapes them. There are many "levers" that societies can pull to influence how we behave. The entire criminal justice system is based on this idea, but the implications extend far beyond crime and punishment to matters of personal happiness, mental health, stable and thriving families, and the fostering of our unique potential.

I have high hopes for the future of evolutionary psychology and so I was honored to be invited to contribute to this new encyclopedia project.

References

Lents N.H. (2019) Maladaptive By-Product Hypothesis. In: Shackelford T., Weekes-Shackelford V. (eds) Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer.