Animal Behavior

What Do Pet Owners Believe About Dog and Cat Emotions?

Pet owners think dogs and cats experience both simple and complex emotions.

Posted March 30, 2023 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- While some philosophers disagree, most dog and cat owners know their pets experience emotions.

- Researchers recently asked pet owners about the number and types of emotions they observed in their cats and dogs.

- There were significant individual differences in the degree to which owners thought their pets experienced emotions.

When he gets excited, Moose, my daughter Katie’s Goldendoodle, is a bundle of joy. But when Katie leaves the house, his mood plummets. He’s down in the dumps with a serious case of separation anxiety. In contrast, Watson, our daughter Betsy’s beagle-mix, is a laid-back canine dude–an even-tempered sweetheart with not much in the way of highs or lows.

Moose's feelings are easy to read–Watson's, not so much. But what do pet owners really know about the emotional repertoire of their companion animals? Lincoln University’s Olivia Pickersgill, Daniel Mills, and Kun Guo recently surveyed 438 dog and cat owners about their pets' emotions. Their results were fascinating and recently published in the journal Animals. (You can read the full report here.)

The researchers investigated the number and types of emotions dog and cat owners ascribed to their pets. Two hundred twenty-seven participants lived with a dog, 93 had a cat, and 68 had both a dog and a cat. They completed an online survey with demographic information about the owners and their pets and a checklist of 22 emotions the animals might experience. The survey also contained a list of behavioral cues of various pet emotions, such as vocalizations, facial expressions, body posture, eye contact, and tail and ear positions.

The list included six primary emotions, presumed to be largely instinctive and biologically based—anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. The list also included 16 “secondary emotions,” such as guilt, embarrassment, and pride. These involve higher brain centers in the cerebral cortex and require greater cognitive capacities.

The Comparative Emotionality of Dogs and Cats

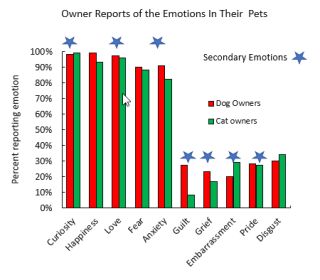

In some ways, the owners were surprisingly similar in attributions of emotions to dogs and cats. For example, as shown in this graph, among the most common emotions reported by owners of both species were curiosity, happiness, love, fear, and anxiety. Similarly, guilt, grief, embarrassment, pride, or disgust were the least common pet emotions.

But in other ways, there were substantial differences in the perceptions of canine and feline emotionality. As a group, the dog owners said their pets experienced an average of 14.3 different emotions, while cat owners said their pets experienced an average of 10.9 emotions. Dogs scored higher than cats on 20 of the 22 emotions. However, more cat owners than dog owners thought their pets got angry. And dog owners were much more likely than cat owners to say that their pets experienced complex secondary emotions–confusion, pain, positive anticipation, guilt, envy, frustration, and sadness.

Pet Owners Differ In Their Views of Animal Emotions

Pet owners, however, do not always agree about the emotional lives of their furry friends. For example, I asked my daughter Betsy and her husband Brion to take the emotionality survey as it related to their dog Watson. Betsy thought Watson experienced 12 of the emotions, while Brion thought Watson experienced only five of them. These differences also appeared in the emotionality scores of pet owners in the Lincoln University study. For instance, some dog owners thought their pets experienced three or four emotions, while others were convinced their dogs experienced all 22 emotions.

Why should there be such large individual differences in what pet owners think about the minds of their dogs and cats? Pickersgill and her colleagues combed their data to answer this question. Surprisingly, they did not come up with much. Men and women did not differ in the number of emotions they thought their pets experienced. Nor were the number of attributions of emotional states to pets related to their owner’s age, cultural background, or mental health profiles.

The researchers found that dog owners with more years of personal experience with dogs tended to think their pets were capable of more emotions. But the effect was quite small. In contrast, dog owners with professional experiences with animals (e.g., working in veterinary medicine or canine behavior training) tended to attribute fewer emotional states to dogs. But, again, the effect was weak.

One variable did affect the evaluation of the cats’ emotional repertoire–the presence of a dog in the house. Pet owners who lived with both species thought their cats experienced only eight of the emotions, while cat-only owners believed their kitty experienced 13.

Among dog and cat owners, the pet’s sex, breed, coat, or body type had no significant impact on the emotionality ratings.

Animal Emotions Controversies

Animal emotions are controversial. The neuropsychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett argued that emotions are a uniquely human phenomenon. In The Guardian, she wrote, “The idea that other animals share our emotions is compelling and intuitive, but the answers we provide may reveal more about us than about them.” In contrast, in an article in the journal BioScience, the ethologist Marc Bekoff argued that there is ample evidence that many species experience complex emotions such as joy, happiness, grief, romantic love, and embarrassment. Indeed, the title of his Psychology Today blog is Animal Emotions.

Nearly all the participants in the Lincoln University study would agree with Bekoff. (Only two said their pets did not experience any emotions.) The study did, however, uncover differences between cats and dogs. The researchers suggest several possible explanations for why owners thought dogs experienced more emotional states than cats. These included owners' greater attachment to dogs, differences in the domestication history of dogs (primarily work) versus cats (primarily pest control), and the fact that owners view dogs as family members more than cats. Most controversially, Olivia Pickersgill and her colleagues suggested that pet owners may be overestimating the emotional capacities of dogs and/or underestimating the richness of the emotional lives of cats.

I was particularly intrigued by the researchers' large variation in the owners' views of emotions in their pets. I would like to know why Betsy and Brion disagreed over whether Watson experienced disgust, guilt, boredom, confusion, positive anticipation, and happiness. I’m hoping the research team’s next project will delve into individual differences in how people view the mental lives of dogs and cats.

References

Pickersgill, O., Mills, D. S., & Guo, K. (2023). Owners’ Beliefs regarding the Emotional Capabilities of Their Dogs and Cats. Animals, 13(5), 820.

Bekoff, M. (2000). Animal Emotions: Exploring Passionate NaturesCurrent interdisciplinary research provides compelling evidence that many animals experience such emotions as joy, fear, love, despair, and grief—we are not alone. BioScience, 50(10), 861-870.