Environment

What Birds Teach Us About Life, Social Change, and Nature

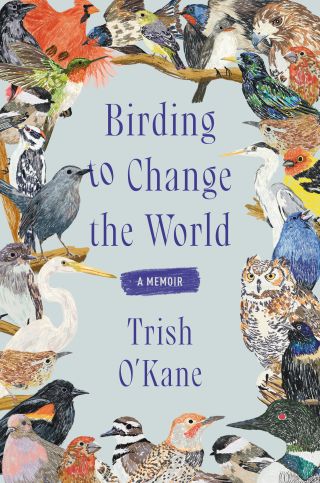

"Birding to Change the World" is a story of science and social engagement.

Posted February 25, 2024 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- "Accidental ornithologist" Dr. Trish O'Kane shows why becoming interested in birds is healthy.

- These amazing beings could help solve our mental health crisis and the current "attention crisis."

- Birds can train your mind to wake up every morning expecting to see something beautiful.

I love watching birds flying here and there, communicating with one another, and observing how they interact with people and other animals. They're a diverse lot of beings in all sizes, shapes, and colors, and when I studied Adélie penguins in Antarctica and the various species who lived around my mountain home outside of Boulder (Colorado), I always felt there were some hidden and not-so-hidden messages because not only did I stop to imagine what life was for them, but I also simply felt good watching them do the things they had to do to live and to thrive.

I never really thought much about how birds could rewild our hearts and souls until I read Priyanka Kumar’s outstanding and profoundly moving book Conversations with Birds and now I more about how they also can "teach us about life, social change, and protecting the environment" after reading Dr. Trish O'Kane's outstanding and highly acclaimed new book Birding to Change the World: A Memoir. Because I now know much more about how birds help us learn about and answer some of life's "big" questions, I feel very fortunate that Trish could take the time to answer a few questions about her groundbreaking book.

Marc Bekoff: Why did you write Birding to Change the World?

Trish O'Kane: I had a debt to repay. After Hurricane Katrina, when I moved to Madison, Wisconsin, the birds of Warner Park helped me out of the worst depression of my life. Then when I saw that the birds' homes were threatened by development, I vowed to help them by organizing my human neighbors, and I vowed to share the story of how the birds helped me.

Another reason I wrote it is because it answers the burning research question I had that was tearing me apart when I stood in the ruins of my home in post-Katrina New Orleans: Can we share this planet with other beings without destroying it? I left Louisiana thinking, No, our species just isn't up to this. But when I moved to Madison to earn a Ph.D., and I began studying the birds of Warner Park, and I saw all the humans and non-humans sharing those 200 acres, I realized—scruffy Warner Park is the answer and the answer is a resounding "yes." Yes, we can share this planet without destroying it if we can just be humble enough to learn from other species.

MB: Who do you hope to reach in your interesting and important book?

TO: I want this book to provoke a wave of starling-style murmurations among these human flocks:

- White birders who haven't thought about the terrible impact of racism in the great outdoors. If even a fraction of the 48 million birdwatchers in the U.S. began attending local police commission meetings, we could save lives. Police brutality is an environmental issue. Racism is an environmental issue—the right to go outside, to lose yourself in the wilderness or just your neighborhood park, without fear. Every year students of color tell me how they are stared at and worse when they wander around white neighborhoods with binoculars (look at what happened to Christian Cooper in Central Park). And I work with many kids of color, teaching them birding. I really worry about some of these little boys as they grow up. Could they become another Trayvon Martin, 17, Aderrien Murry, 11, or Tamir Rice, 12? (Sickeningly, there are thousands of names.) Most birders are smart, dogged, well-organized, observant and, I firmly believe, thoughtful and kind. White birders could have a huge impact on policing if we'd advocate for our fellow humans—not just our fellow avians.

- Some of the 48 million birdwatchers who do not vote or participate in local politics. I want the love they feel for our avian neighbors to fire them up and send them crow-mobbing style to public meetings to demand that we keep local birds healthy by changing lawn ordinances to replace lawns with wildflower meadows; to demand local bans on pesticides and herbicides; and to educate local officials about climate change. This would be a mighty murmuration far more powerful than a lobby like the NRA, which has less than 5 million members.

- Parents and education policymakers. We need a dramatic murmuration in education policy—a radical turning of wings to liberate teachers from testing mandates that are not only wearing educators out but are making children sick by imprisoning them in little desks all day long, inside, which goes against the recommendations of more than 100 public health studies. I grew up with triple the recess time kids have today, and then after school, I went home and ran around with my brothers on the 100-acre orange ranch where my parents worked. This is a human right—to play outside. Every child in this country deserves that right and not because they're in a forest school or homeschooled or their parents are able to pay for fancy summer camps. This is a new form of segregation between kids in public schools imprisoned inside and wealthier kids in private "forest" schools who get to learn outside and reap the health benefits.

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass said, "It's easier to build strong children than to repair the souls of broken men." We are not building strong children in our schools. Pediatric occupational therapists report that children today are weaker in muscle mass and core strength than children decades ago. They cannot focus and we are medicating them to make them sit still.

MB: Why should readers of Psychology Today be interested in your book?

TO: There is a massive mental health crisis among the young which I see every day, particularly among my very anxious undergraduates. At universities today, we are no longer afraid of the COVID pandemic—we are terrified of a suicide pandemic. More psychologists could incorporate birding and nature walks into their practices. Psychologists could testify before school boards and lobby for more recess time and less screen time. Immediately after Katrina, I could not sit inside staring at a screen, which is what I had done for years as a journalist. My brain was shot. I couldn't focus. The only thing that felt good was to sit outside on the ground, listening to the wind whistling through the trees. My breathing deepened, my heart rate slowed and my nervous system began to calm down.

In 13 years of teaching birding, every semester my students tell me how they feel better after they do their birding homework. Because birds turn you into an optimist—they train your mind to wake up every morning expecting to see something beautiful, something miraculous, anywhere and everywhere. And birds also help us focus, which could solve the current "attention crisis."

References

In conversation with Dr. Trish O'Kane. a writer and a senior lecturer in environmental justice at the University of Vermont, where avians are her teaching assistants. A former human rights journalist in Central America and the Deep South, she has written for the New York Times, Time, and the San Francisco Chronicle.

How Birds and Nature Rewild Our Hearts and Souls; The Other Side of Silence: Rachel Carson’s Views of Animals; Trees Lower Medication Sales for Heart and Mood Disorders; The Heartbeat of Trees: An Uplifting Spring Read; Why It's Essential to Listen to the Hidden Sounds of Nature.

Eftaxia, Giota. The Powerful effect of the sound of nature on human health. Radio Art, 2021.