Eating Disorders

How Anorexia Damages Our Mental Capacities

The basics of anorexia and cognitive impairment. Questions to ask.

Posted May 24, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- When we observe correlations between an illness and cognitive deficits, we can also ask causal questions.

- Unraveling correlation and causation to find out what illness does and what changes with recovery.

- There is a vast amount of research on cognitive deficits in anorexia.

What does anorexia nervosa do to the mind? This is a question that most of this blog circles around in some way or another. Whenever we talk about the experience of having an illness (as opposed to, say, the physical damage it’s doing), we talk about how the illness is bound up with patterns of thought and emotion that would not exist without it. Maybe we wouldn’t be so miserable, irritable, distractable, obsessive, compulsive, and selfish, without it.

But of course, when our sample is merely ourselves, we don’t actually know whether these ways of thinking and feeling would have existed without it. Maybe we were just going to get more like this with age anyway. We therefore also don’t know what difference getting rid of the illness will make, and this ignorance impacts the cost-benefit analysis of whether recovery (which takes time and is hard) is worth it. After all, humans are always highly motivated to find excuses not to do hard things. And with an illness that has strong egosyntonic elements (Gregertsen, Mandy, and Serpell, 2017), that binds itself up so tightly with our ideas about who we are and makes itself seem to fit so well with them, we are even more keenly on the lookout for reasons not to leave it behind us. That imperative may stretch as far as inclining us to pretend that the illness isn’t really doing that much damage after all.

I’m sure you know all about the impact of malnutrition on the physical system that is a human being, from a devastated skeleton to digestive and immune system dysfunction and muscular atrophy, including the important muscles in the heart. But maybe you’re a bit hazier about the mental damage done by eating less than is good for you over an extended period. I thought it was time (after 14 years of not tackling it on this blog) to address cognitive impairment in anorexia head-on. Let’s start at the beginning.

Whenever you have an illness (for example, anorexia nervosa) and you have some characteristics that seem to go along with it (cognitive impairments of numerous kinds), there are a few basic questions you can ask. They’re all variants of the simple, fundamental question at the heart of the scientific method: Is this correlation or causation? Starting from the observation of correlations between anorexia and cognitive impairment, we can ask, for example:

- Does the impairment predate the illness?

- Does the impairment resolve when the illness is over?

- Is the impairment caused by any specific part of the illness?

- Does the impairment affect genetically related people without the illness?

- Does the impairment prolong the illness?

There is, it turns out, a vast amount of research on cognitive deficits in anorexia. In this miniseries, I’m going to focus on the cognitive side (that is, on how people perform cognitively or what they say about how they perform), not on the neurophysiology or neurochemistry (that is, how their brains are structured or are functioning in physical-chemical terms)—mainly because looking at those brain features takes us a step further away from what we probably care about, which is what having anorexia is like, and how not to have it. (For a great overview of the physical effects of semi-starvation on the brain, listen to this episode of Chris Sandel’s podcast, “How restriction affects the brain,” or alternatively read the full transcript, here.) I’ll also focus on anorexia as opposed to other eating disorders.

This is obviously not a formal review or meta-analysis, and my methods have been simple:

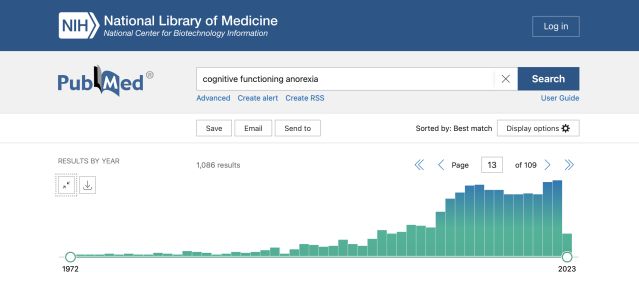

- Search PubMed for "cognitive functioning anorexia”

- Review the first 13 pages or 130 hits. I stopped at 130 because the results were gradually getting less relevant, and because I’d had enough.

I’ve not referenced all the 130 papers I looked at here, but I’ve done my best to accurately convey the major trends and outliers. Overall, I’d say that the research allows us to answer Questions 2 and 5 above with a high level of confidence, addresses Questions 3 and 4 with a middling to low level, and leaves Question 1 mostly unanswered. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

In the next part of the series, we’ll take a look at the evidence for the simple correlation: that anorexia goes hand in hand with a lot of what looks like cognitive impairment, or the mind not working effectively and efficiently.

References

Gregertsen, E. C., Mandy, W., & Serpell, L. (2017). The egosyntonic nature of anorexia: An impediment to recovery in anorexia nervosa treatment. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2273. Open-access full text here.