Happiness

How Do We Measure Happiness?

The most subjective thing imaginable can be expressed quantitatively.

Posted May 6, 2019

Bookshelves and blogs are full of advice about being happy. Philosophers have theorized for centuries about definitions of "happiness" and related terms. But we don't get very far in science before we have a clear procedure for measuring something. How can someone claim to actually measure happiness? Isn't it a feeling? Isn't it intangible, abstract, spiritual, subjective?

It turns out measurements can be subjective but at the same time quantitative. Being able to quantify the human feeling of well-being after two thousand years of not knowing how is no sudden, headline-making scientific breakthrough like solving the genetic code. Yet, given how focused the world has become on some other economic objectives, I can't help but see it as the turning point in a revolution for human society. More on that in a later posting.

It is useful to understand the breadth of ways different disciplines quantify well-being. Below I describe the measure of life satisfaction, which many researchers, advisory agencies, and policymakers are treating as the "right" way to think about an overarching measure of happiness for individuals, communities, regions, and countries.

In a later post entitled “How not to measure happiness”, I will talk about some of the other ways that people have tried, or are still trying, to fill that same purpose. For instance, health researchers think about "Quality-adjusted life years", economists think about "revealed preference", and governments almost everywhere talk about average income as though it measures well-being. There are other approaches, too, and I'll mention why they are all flawed in ways that life satisfaction isn't.

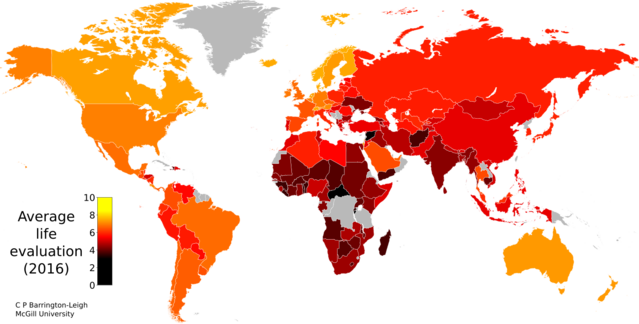

“Measuring” life satisfaction is really simple. It's the response you get when asking, “Taking all things into account, how satisfied are you with your life these days on a scale of 0 to 10? Zero means completely unsatisfied, and 10 means completely satisfied.”

On the surface, this does not seem very scientific! Yet, this kind of question is asked in many different translations in 150 countries every year. Don't values differ among cultures? In addition, people are surely influenced by mood, so one might expect overall life evaluations to be affected by short-term conditions like the weather, or what someone said to them five minutes ago. Also, don't people just have different traits, so that some might be genetically or otherwise predisposed to be happier?

If we want to infer anything scientific about what decisions, circumstances, or policies make people happier, answers need to reflect more than just spurious influences on people.

Such skepticism was a good place to start a few decades ago, when economists started paying attention to quantitative, subjective life satisfaction data. Decades of research have largely assuaged these doubts. While they are well-founded, the important question is, in each case, how big is the problem? In particular, statistics can tell us how big the short-term bias, the personality variation, or the cultural effect is as compared with the influence of real-life circumstances that could be changed by policy or individual choice.

In the meantime, what can you do with the Life Satisfaction question? Interestingly, although people willingly answer it on anonymous surveys, it is a deeply personal question. Outside of research, I use it in two ways. First, I track my own life satisfaction, quantitatively, by recording it in my diary every month or so, and this helps me remember what I've been through and reflect on which circumstances in my life have been best and worst for overall well-being. Doing this is somewhat analogous to ending each day thinking about its highs and lows, but life satisfaction gets at the deeper, more enduring supports, connections, and meaning in life.

Secondly, I sometimes ask the question to close family and friends. It can be a soul-touching way to catch up with or become aware of changes in their lives. It is intimate and can cut through a lot of superficial news we sometimes use to cover up both challenges and successes. With some people, I wish I had used the question more often.

References

OECD (2013) OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being (OECD Publishing)

Stone, Arthur A, Christopher Mackie et al. (2014) Subjective well-being: Measuring happiness, suffering, and other dimensions of experience (National Academies Press)

Helliwell, J., Huang, H. & Wang, S. in World Happiness Report 2017 (eds Helliwell, J., Layard, R. & Sachs, J.) Ch. 2 (Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2017).